In the early 1940s spinach and endive crops in Southern California began turning funny colors—first bronze and silver, then black and dead. After ruling out pests and disease, scientists traced the problem to smog blowing over from nearby Los Angeles. Concerned local officials quickly banned backyard incinerators and capped emissions from industrial plants that burned coal and pumped out smoke.

Nothing changed. Crops kept dying, and local air only got worse: Hollywood studios began canceling outdoor shoots, and office workers had to abandon buildings downtown on particularly bad days. To scientists, blaming industrial plants didn’t make sense anyway. Smog from burning coal—common in Pittsburgh and London—didn’t normally damage crops. Furthermore, as chemical instruments tycoon Arnold Beckman pointed out, smog in those places had a sulfurous smell (like a match) and appeared yellow or black. Los Angeles smog turned the air brown and smelled of bleach instead. But if this wasn’t classic coal smog, what was it? No one knew, until a Dutch chemist named Arie Haagen-Smit got fed up breathing foul air.

As a child Haagen-Smit played hide-and-seek with his siblings among stacks of bullion at the Dutch mint, where his father worked as a chemist. He then followed his father’s career path and studied chemistry in college at Utrecht, doing well enough to get recruited to Harvard University and then Caltech, where he joined a so-called Dutch mafia of Netherlander scientists.

His research focused on isolating flavor compounds in plants—radishes, beans, cashews, onions, garlic, even marijuana. In the mid-1940s he started working on pineapples, importing 6,000 pounds’ worth from Hawaii. After peeling and chopping them, he evaporated the flavor-rich juice using low pressures. He then condensed the juice with cooling traps and distilled it to concentrate flavor. The process wasn’t exactly efficient: 6,000 pounds of pineapples yielded a few grams of solution. But he succeeded in isolating the chemicals that make up pineapple’s smell and flavor.

Although he was content with this work, Los Angeles’s growing pollution bothered Haagen-Smit: some days he could actually taste the smog. So in 1948, at the urging of Beckman, he rejiggered his pineapple-testing apparatus and blew a few hundred cubic feet of polluted air (roughly what an Angeleno inhaled each day) through the cooling traps. Out dripped several ounces of a “vile-smelling” brown sludge—eau de smog.

Among other pollutants, tests revealed ozone in this liquid smog, which explained the bleachy odor. It also presented a puzzle since no local industries released ozone. Haagen-Smit had his suspicions, though. By the early 1950s Los Angeles had two million cars on its roads, all of them releasing nitrous oxides in their exhaust. The incomplete burning of gasoline also released gaseous hydrocarbons, as did oil refineries.

By themselves neither nitrous oxides nor hydrocarbons could explain the smog; there had to be an extra ingredient. And Haagen-Smit soon identified it—that famous California sunshine. He guessed that light was catalyzing a reaction between these chemicals, and sure enough, when he pumped hydrocarbons and nitrous oxides into a chamber and exposed them to light, smog billowed out the other end.

Scientifically, this was a whole new type of pollution. Unlike classic pollutants, which got released directly into the air, L.A. smog formed only when these man-made chemicals interacted with natural sunshine. The experiment soon became a classic in environmental chemistry—not to mention a major headache for carmakers, who worried about their reputations.

Beckman knew of their worry and, in an inspired bit of mischief, used it to his advantage. He arranged for Haagen-Smit to attend a lecture where industry advocates accused the Dutchman of biased and incompetent science. As Beckman predicted, Haagen-Smit threw a fit and soon abandoned plans for more pineapple work in order to study smog full time. He ran several more damning experiments and gave public lectures where he whipped up smog on demand, leaving the audience choking.

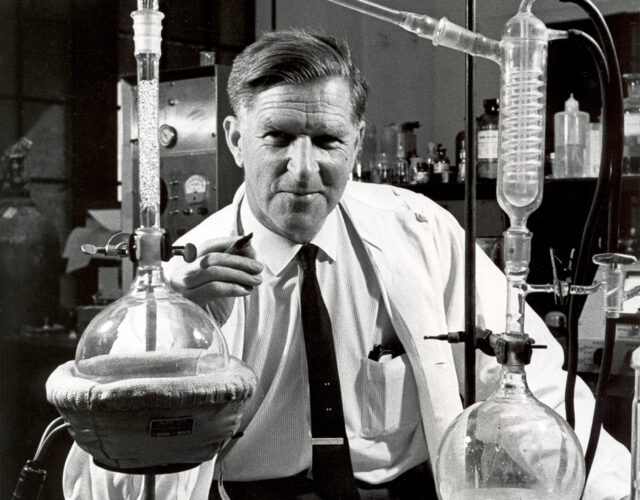

Haagen-Smit giving a lecture on smog, ca. 1960s.

Eventually, he became a full-time advocate for pollution control, serving on several regulatory bodies. In the 1970s, research by Haagen-Smit and others finally convinced the federal government to adopt emissions standards on cars and mandate catalytic converters to break up smog precursors. He’s a major reason why Los Angeles, although packed with 14 million vehicles today, has cleaner air now than in the 1950s.

When he died in 1977—known popularly as Dr. Haagen-Smog—he was one of the most famous environmental activists in the country. But Haagen-Smit always felt slightly uncomfortable in that role. He cared about air quality, certainly. But even more, he loved the science of smog—studying where it came from and how it circulated day by day. “If I look at the daily graph to see how much smog is in the air,” he once admitted, “I feel a twinge of disappointment when there’s just a small amount.” He’d grown to love, at least a little, the flavor of smog.