Lindsey Fitzharris. The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine. Scientific American, 2017. 290 pp. $27.

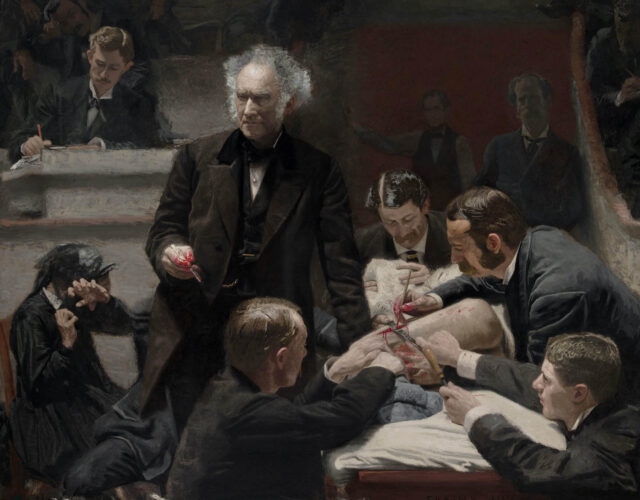

In 1875 Thomas Eakins, a realist painter who later became known for his studies in motion photography, watched as one of the United States’ most prominent surgeons, Samuel D. Gross, removed dead tissue from a patient’s infected thigh bone. Eakins was at work on what would become The Gross Clinic, an 8-by-6½-foot oil painting set in the surgical amphitheater at Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College. The image is at once grim and alluring, and according to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, it is “one of the most often reproduced, discussed, and celebrated paintings in American art history.”

Gross, 70 years old when Eakins created the painting, is presented as a master of his craft, clad in a black frock coat, his blood-soaked fingers daintily wielding a scalpel. The painting has the look of a commissioned work, an act of self-veneration, one that Lindsey Fitzharris, author of The Butchering Art, sees as a celebration of Gross’s “faith in the surgical status quo”—the doctor’s way of conveying that dim operating theaters and unsterilized instruments were working just fine, thank you very much. Yes and no. Gross did not commission the painting; instead alumni raised $200 to purchase it for the college after it was shown by Eakins at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. The alumni were a cocksure group, and Eakins’s painting was a powerful representation of their best and brightest.

That same year Philadelphia also hosted the International Medical Congress, where an English surgeon named Joseph Lister spoke about a new approach to surgery he had developed over the previous 25 years. The Americans were largely unconvinced by his argument that filthy hands, instruments, and operating tables harbored invisible germs that caused postsurgical infection. “Little, if any faith, is placed by an enlightened or experienced surgeon on this side of the Atlantic in the so-called treatment of Professor Lister,” Gross sniffed. But Lister was right, and a medical revolution was already afoot.

While American doctors may have initially rejected germ theory, they deserve credit for conquering surgery’s foremost obstacle—pain—with the first use of surgical anesthesia in Boston on October 16, 1846. The news took two months to reach London, where surgeon Robert Liston, aka the “fastest knife in the West End,” tested what he referred to as “a Yankee dodge” (ether) during a mid-thigh amputation. It is here Fitzharris begins her account, in the operating theater where Lister, a 19-year-old medical student sitting near the back of the room, crosses paths with Liston, “one of the profession’s last great butchers.”

In gory detail Fitzharris guides us through the stuffy surgical theater of mid-19th-century London, where surgeons wore the same “blood-encrusted apron” for every surgery and “the floor was strewn with sawdust to soak up the blood that would shortly issue from the severed limb.” This is not a book for the squeamish; it’s informative but graphic, with sutured guts and pus-filled abscesses aplenty. And in the dissection room, well, “The top of the cadaver’s skull had been removed and was now sitting on a stool next to its deceased owner. The brain had begun to degrade into a gray paste days earlier.” Were he still around to do so, the sober, Quaker-born Lister might criticize the prose as a bit too vivid, but Fitzharris plays to a youngish crowd with a keen interest but probably no formal education in medicine and medical history. This is an audience fostered by her YouTube series Under the Knife, as well as the 2014–2015 Cinemax show The Knick and recent books, such as Dr. Mütter’s Marvels by Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz and The Sick Rose by Richard Barnett.

Undated photogravure of Joseph Lister.

Lister is a perfect fit for this crowd. He’s a household name, though not quite for the reasons we might assume during our daily gargle with Listerine, and his impact on medicine was vast. When Lister left the operating theater that December day in 1846, having watched Liston perform his ether experiment, he was, like the other students around him, probably elated by the development. “Nevertheless,” writes Fitzharris, “as Lister made his way through the crowds of men shaking hands and congratulating themselves on their choice of profession and this notable victory, he was acutely aware that pain was only one impediment to successful surgery.” The other, of course, was the constant and mysterious threat of postoperative infection, which actually worsened after the popularization of anesthesia. At Massachusetts General Hospital, where surgical anesthesia was introduced, mortality rates from amputations rose from 19% to 23%. And given that removing a tumor or a limb could now be painless, more patients lined up for treatment, and so more died of infection.

Lister had a leg up on his fellow practitioners. His father, Joseph Jackson Lister, was a wine merchant and an inveterate tinkerer. Microscopes were his particular focus, and he even designed an achromatic lens that led to greater optical resolution. He shared his hobby with his son, who became one of the only medical students of his time to carry a microscope alongside his velvet-lined amputation kit, much to the chagrin of his instructors, who “believed the microscope was not only superfluous to a study of surgery but also a threat to the medical establishment itself.” All patients really needed, they groused, was hands-on treatment. But Lister, taking a cue from French physicians, believed in the value of research, even if quantifiable benefits remained elusive.

The hospitals of the time were microcosms of London: dirty, smelly, and overcrowded. In short, they were ideal for spreading disease to both patients and doctors. Were small organisms called animalcules to blame? Or poisonous vapors in the air? No one yet knew about microscopic bacteria. But what made Lister stand out was his willingness to experiment and to learn.

In 1852 Lister made two major observations: first, that cleaning a “rotting ulcerating wound” with a highly caustic chemical seemed to promote healthy healing; and second, that under the microscope, the pus he had scraped out of infected patients looked as if it were filled with “some bodies of pretty uniform size” for which he had no name but referred to as “materies morbi,” or morbid substances. His investigations found little support among London’s medical men, however, and he moved to Scotland, where the medical community was considered more open to new ideas.

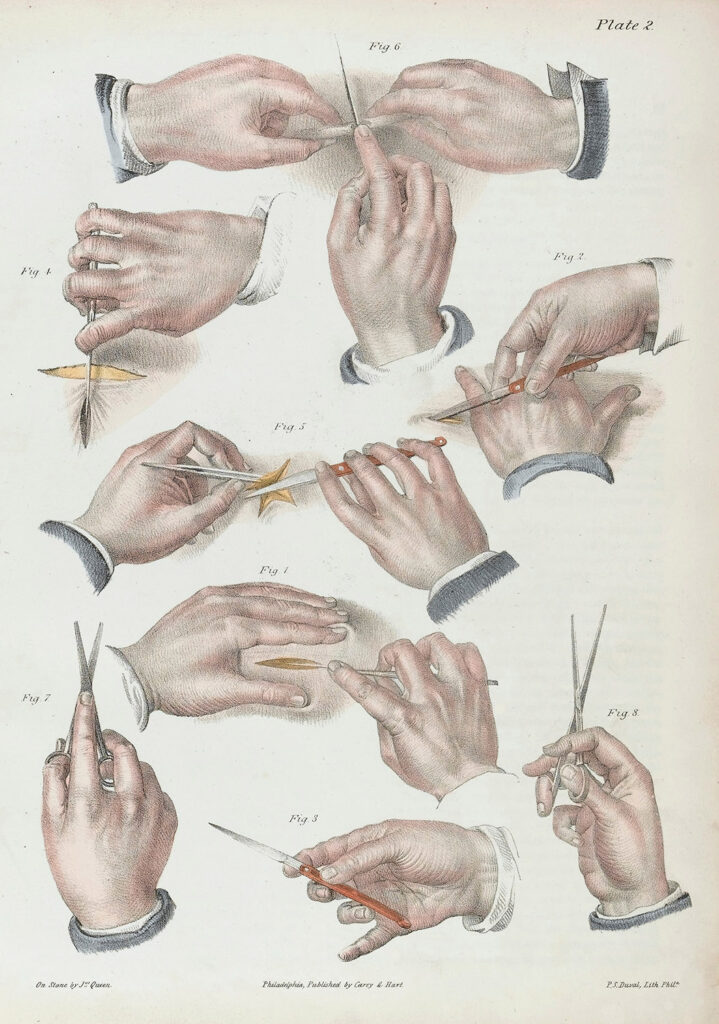

Illustration from Joseph Pancoast’s Treatise on Operative Surgery, 1846. Lister’s application of germ theory and adoption of antiseptic treatments revolutionized surgery in the second half of the 19th century.

Even there Lister was thought strange. The man dissected frogs at home! And he tried to impose new rules—open windows, swept floors—first at the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh and then in Glasgow in a futile effort to lower mortality rates. Not until a colleague introduced him to the work of Louis Pasteur in 1864 did Lister’s earlier observations begin to make sense.

Lister lost no time in applying what he gleaned from Pasteur’s theories on fermentation and putrefaction. On the surgical ward he treated wounds with carbolic acid washes. His first successful case involved an 11-year-old boy whose tibia had been cracked by a metal-rimmed cart wheel, leaving an open wound. The boy was spared infection and likely amputation through the disciplined use of an antiseptic. Lister spent another two years running trials with carbolic acid solutions before announcing his results in the Lancet in 1867. The numbers spoke for themselves: Fitzharris writes that “not a single instance of pyemia, gangrene, or erysipelas had occurred on Lister’s wards since he had introduced his system.”

Lister had yet to gain the full confidence of the British medical community when in 1871 an urgent telegraph summoned him to treat Queen Victoria, who was on holiday in Scotland. Lister found the queen suffering from an orange-sized abscess in her armpit. He brought with him his latest brainchild, carbolic spray, which he created after physicist John Tyndall’s experiments showed high amounts of dust particles, bacteria, and mold spores in the air. Lister operated, and Victoria lived another 30 years. The queen’s recovery bolstered people’s faith in Lister’s approach.

Lister was tireless in his research—his notes on catgut ligatures alone span 29 years—and pragmatic in his proselytizing. He gave up on the “old guard” of medicine and devoted himself to training a new generation of surgeons and to sharing his methods abroad, as he did on an 1876 tour of Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and San Francisco. In the end accolades piled up long before his death in 1912, not only in the form of prizes and honorary degrees but also in the name of the mouthwash invented by Joseph Joshua Lawrence that remains popular to this day. More to the point Lister saved countless lives. As Fitzharris concludes, “Lister’s methods transformed surgery from a butchering art to a modern science, one where newly tried and tested methodologies trumped hackneyed practices.”

As for Thomas Eakins, he too weighed in on germ theory with a second painting, completed in 1889 and titled The Agnew Clinic. The operating theater scene is similar to that of the earlier painting, except it is lighter and brighter and the doctors wear white lab coats, signifying a more sanitary environment. According to Fitzharris, “It is Listerism, triumphant.”