In 1943 one of the most important artists in the world was arrested for the second time in two years. Hashime Murayama, a 64-year-old scientific illustrator, had been living in the United States for 37 years by then and was engaged in vital research focused on detecting cancer in women. But as a Japanese national during World War II, he ran afoul of the Alien Enemy Hearing Board, whose job was to root out Axis spies. The board ordered the police to seize Murayama and drag him to an internment camp.

For Murayama it was a stunning fall from his prosperous early years in the United States. After studying art in Kyoto he moved to New York City in 1906 and found work at Cornell University Medical College painting images of cells and preparing anatomical specimens. He even earned a patent in 1914 for developing a new way to mount biological tissues for photographic reproduction.

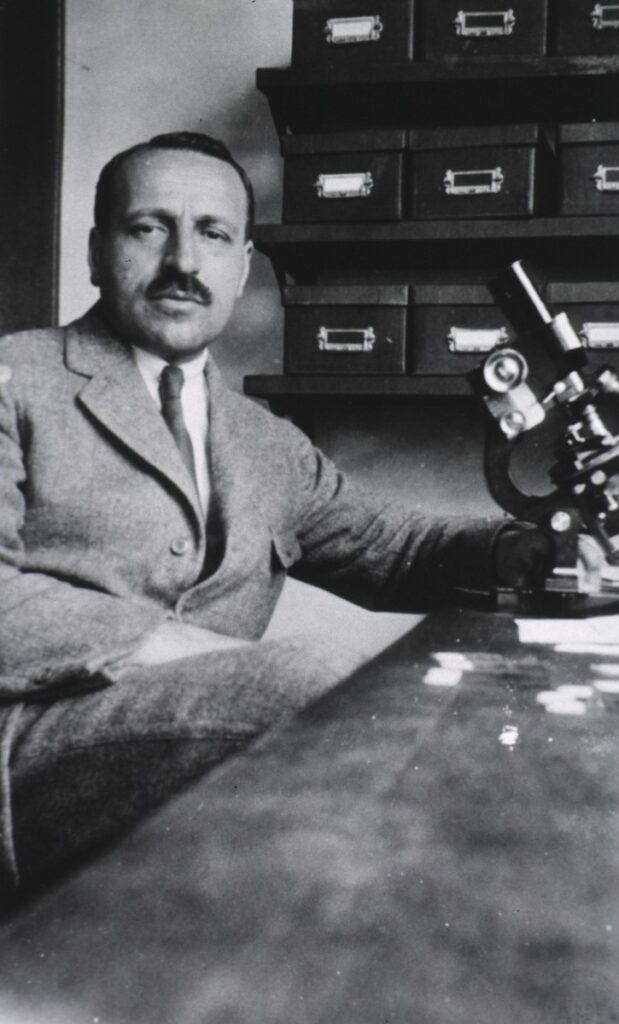

At Cornell he also became friends with a cell biologist and fellow immigrant named George Papanicolaou, who worked on, of all things, the menstrual cycle of guinea pigs. The two men had neighboring offices, and Papanicolaou adored the artistry of the cells Murayama painted.

But Murayama’s real passion was wildlife art. Whenever possible, he would spend a day at the New York Aquarium, watching the fish slip through the water and studying their rich coloration. And while other wildlife painters often simply smeared some black in the background, Murayama took the time to detail the fishes’ environment—the plants and rocks and flotsam that made up their world.

Impressed by Murayama’s work, National Geographic hired him as an illustrator in 1921, luring him to Washington, D.C. He and his wife, Nao, bought a home there and raised three children. At the magazine he specialized in artistic depictions of fish, birds, and insects, working from both live specimens and preparations in jars. Editors there admired his unique combination of accuracy and romantic flourishes. Staffers remember him counting the scales on fish to get the number correct; at the same time, the finished illustration practically radiated the warmth of the sun-dappled water.

The next two decades passed pleasantly for Murayama, and he had a happy retirement to look forward to—until World War II upended everything. Even before Pearl Harbor anti-Japanese sentiment was strong in the United States. Sources differ on what exactly happened with Murayama, but in mid-1941 he left—or was fired from—National Geographic. (His replacement ironically was German.) Then, immediately afterward, Murayama got a message from New York. His old friend George Papanicolaou wanted to talk.

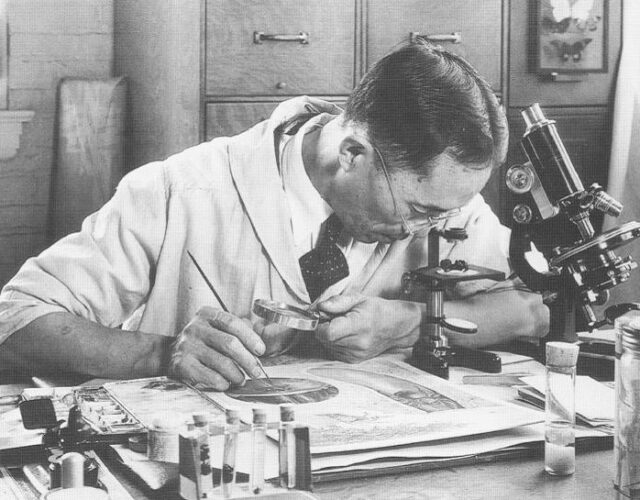

Papanicolaou had had an up-and-down couple of decades since Murayama left Cornell. By the early 1920s the doctor had shifted focus from the menstrual cycles of guinea pigs to the menstrual cycles of humans, with a special focus on disorders of the female reproductive tract. Along the way, he had discovered something startling: he could diagnose cervical cancer in women simply by studying the nuclei of their cells.

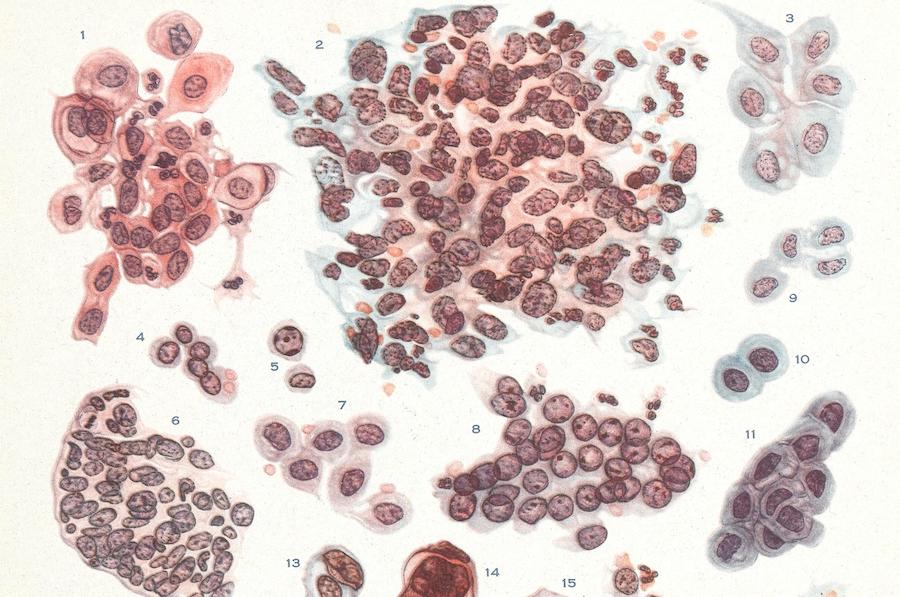

Papanicolaou would dab some cells from the cervix with a cotton swab. Then he would smear the cells on a glass slide, stain them with dyes, and study them under a microscope. Cancer cells, he had learned, looked quite different from healthy cells. They had distorted membranes and dark, swollen, fragmented nuclei. Excited by these results—here was a brand-new way to detect cancer—Papanicolaou presented his findings at a conference in 1928.

It was a total flop. First of all the conference was a poor fit. His boss was a eugenicist and had pushed Papanicolaou to present at a so-called Race Betterment Conference in Michigan. Most attendees had other, more sinister issues on their minds.

But even the doctors present frowned. Why did they need this new diagnostic tool? They already had biopsies, which detected cancer by removing a bit of a tumor with a needle; they would then study it for abnormal tissue architecture. Biopsies also gathered far more cells than a cotton swab. All in all Papanicolaou’s technique seemed pointless.

Chagrined, Papanicolaou all but abandoned the research for the next decade. But in 1939 his eugenics-loving boss died, and the new department chair encouraged him to get back into the cancer game. Papanicolaou agreed—in part because he’d been rethinking the purpose of the work anyway.

Biopsies were important, certainly. The problem was, you had to know a tumor was there before you would have any reason to perform a biopsy. And cervical tumors rarely produced symptoms until they were advanced and dangerous. So what if Papanicolaou’s smears could detect cancer early—or better yet find precancerous growths? What if their real value was as a screening tool?

Starting in 1939 Papanicolaou redoubled his efforts. People, he reasoned, don’t just wake up with full-blown cancer one day. The membranes and chromosomes and nuclei of their cells change in a step-by-step process from normal to malignant. So by studying cells under the microscope he could identify women who seemed likely to develop cervical cancer. And he knew that this type of cancer would be especially good to catch early. In their initial, not-yet-cancer stages these tumors tend to be superficial, confined to the surface of the cervix. At that point they’re easy to remove. Once they develop into full-blown disease, though, cervical tumors invade and burrow into other tissues, often with fatal results. Early detection is key.

For all its promise Papanicolaou’s screening technique had one big shortcoming. He had decades of experience examining cells, but some of the signs of precancer were subtle. Other doctors might struggle to see them, especially at first. To make his smears useful to others Papanicolaou needed to train pathologists to spot the telltale signs. He needed visuals. He needed art. He needed his old friend Hashime Murayama.

Papanicolaou reached out to Murayama after his split with National Geographic and offered him a job in New York illustrating cervical cells. By any measure this work was a step down for Murayama—from painting gorgeous birds and fish for one of the most prestigious magazines in the world to working as a technician sketching cells in a medical office. But lacking other options Murayama signed his house in Washington over to a son (who was a U.S. citizen and enjoyed the rights thereof) and headed back to New York.

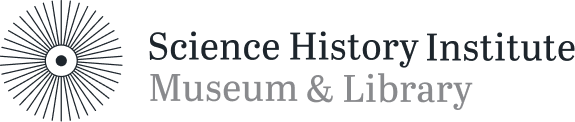

Thus began one of the most important collaborations in the history of cancer research. While Papanicolaou squinted at cells, Murayama drew them and charted the course of cancer. To do the artwork he relied on what’s called a camera lucida. This device uses a lens and prism to superimpose an image of what the artist wants to draw—such as cells under a microscope—onto a piece of paper. Murayama had always loved technology, and the camera lucida aided him in producing accurate sketches of cells.

But Murayama did more than just mechanically reproduce what he saw. When the sketch was finished, the art began, as he added the colors of the dyes—dusty pinks and pale oranges, steel blues and blood reds. He also developed a technique for drawing cilia and other fine structures using a brush from which he’d removed all but a single bristle. And beyond artistic technique Murayama’s biggest skill was his ability to look at a messy jumble of cells on a slide and reproduce just one or two that best captured the essence of cancer. As with all artists he had to extract the ideal from the actual.

Most impressive was that he did this work amid continual harassment for being Japanese. In 1942 and again in 1943 the Enemy Alien Hearing Board had Murayama arrested—in part because one of his sons worked as a journalist in Japan and was reportedly writing propaganda for radio broadcast. The Murayama house in Washington also got ransacked by agents looking for evidence of espionage.

Remarkably, though, U.S. attorney general Francis Biddle stepped in and freed Murayama. Papanicolaou had pleaded with the board on behalf of his friend, arguing that the artist’s sketches of cancer cells were vital to the advance of medicine. Biddle agreed: “It is said,” Biddle noted in his ruling, “that he is the only person in the United States who can do that kind of work.” By that point Murayama had spent five months detained at Ellis Island, but he was better off than the many Japanese Americans held at internment camps for the duration of the war.

Murayama worked steadily throughout the ordeal with the Enemy Alien Board, and in 1943 Papanicolaou published dozens of Murayama’s drawings in a book about cervical cancer. Given the unwieldy name of Papanicolaou the medical community eventually shortened the term for his technique to the Pap smear.

Pap smears seemed so promising for cancer prevention that in 1952 the National Cancer Institute sponsored the largest screening trial in its history. Approximately 150,000 women in southwestern Tennessee received Pap smears—some in clinics but most in mobile “Pap stations” set up at businesses and schools. The cells were then sent to a clinic in Memphis where platoons of young women sat at microscopes and scrutinized the smears for cancer. Whenever they had a question about some dubious-looking cell, they glanced up at the wall. Hanging there as guides were Murayama’s original watercolor paintings. In some the pencil marks from tracing with the camera lucida were still visible.

The Tennessee screening trial was a triumph: the young women at the microscopes flagged 557 precancerous tumors, all in asymptomatic women who probably would have died if not for the tests. In a wider sense the trial proved that Pap smears could be scaled up to screen large populations and find cancer without the need for painful biopsies. Pap smears are now considered the most successful cancer screening tool in history and have cut the mortality rate for women with cervical cancer by 70%.

Given his decades of work on cell smears, George Papanicolaou deserves the lion’s share of the credit here, and he remains celebrated today. In May 2019 Google even produced a home page doodle of him for his 136th birthday. But Papanicolaou’s smears never would have moved beyond the hallways of Cornell without his largely forgotten collaborator Hashime Murayama. In the Google doodle, in fact, Papanicolaou is holding up a slide that shows not actual cervical cells but the spitting image of one of Murayama’s renditions.

There’s an old adage that says life is short, art long. And in certain circles Murayama’s wildlife art remains celebrated to this day. But even though he took Papanicolaou’s assignment under duress, Murayama’s work on cervical cancer had the more lasting legacy—art that helped make millions of women’s lives longer.