Autumn in Philadelphia usually brought people outdoors, but this year the city was all shuttered up. Although it had been several months since it first appeared, the epidemic still raged, and no one really knew when it would end. Doctors urged people to stay home, avoid unnecessary contact, and observe good personal hygiene.

Citizens still argued among themselves about the disease, and while many scoffed at the recommendations from so-called experts, most grudgingly listened. And so the lockdown halted commerce and disrupted the normal rhythms of social life. As one observer remarked, “Business . . . became extremely dull. Mechanics and artists were unemployed; and the streets wore the appearance of gloom and melancholy.”

Such was the scene when yellow fever ravaged Philadelphia in 1793, although it could just as well describe the city, or most any American city, in fall 2020 at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It’s been said many times during the past two and half years that the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented in American history. But the nation’s history has now been bookended by two great outbreaks. The first began when yellow fever struck Philadelphia in 1793, killing 5,000 of the city’s 50,000 inhabitants, and continued to 1805 in a series of terrifying epidemics that scourged New York and Philadelphia. Close attention to the nation’s first epidemic reveals striking similarities with its most recent. From the lack of preparation to ruthless politicization of medical opinions, yellow fever anticipated much of what we have come to know and lament about COVID-19.

Yellow fever is caused by a virus that spreads through the bites of female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. It is often classed with tropical diseases, such as malaria, dengue fever, and more recently Zika fever, but it is far more violent. The name of the disease comes from the jaundice it produces as the virus pummels the victim’s liver. Even in modern settings, mortality rates are as high as 5%, and death comes in a grisly, painful manner, from massive internal hemorrhaging.

Before it arrived in Philadelphia in 1793, yellow fever was a relatively common disease in the Atlantic. It was certainly well documented and described in the medical literature of the period, something every trained physician would have read about. Although the fever made sporadic appearances in Philadelphia, New York, and Charleston, its true home was in the sugar colonies of the Caribbean.

During the Seven Years’ War (1754–1763), the fever tormented the French, Spanish, British, and American soldiers who trespassed in Caribbean waters. Merchants who plied the routes between the major commercial centers of British North America and the Caribbean islands always knew the danger that lurked there. As Americans began importing more sugar, coffee, and rum from the islands in the years leading up to 1793, some must have guessed that someday yellow fever would come along too.

And come it did. From 1793 to 1805, yellow fever visited the United States every year. After the great epidemic of 1793, it returned to Philadelphia with devastating effect in 1797 (≈1,500 deaths), 1798 (3,645 deaths), and 1799 (≈1,000 deaths); it assailed New York in 1795 (≈800 deaths), 1798 (2,080 deaths), and 1803 (≈700 deaths); it raged in Baltimore in 1800 (1,197 deaths); and it occurred in several minor epidemics in Boston, Charleston, and New Orleans. The fever also chased the government from Philadelphia and disrupted commerce for months at a time. Yellow fever was the most serious natural problem that the early United States faced.

An Aedes aegypti mosquito feeding. Photo by James Gathany.

While the virus known as SARS-CoV-2 first crossed over from bats to humans in 2019, the specter of a global pandemic had haunted the world for years. The global community narrowly avoided wasting pandemics in 1997 with avian influenza, in 2002 and 2003 with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and again in 2009 and 2010 with H1N1 influenza. All were highly contagious viral diseases that spread easily through respiratory secretions.

Public health agencies around the world sounded the alarm and many, such as the Centers for Disease Control in the United States, crafted plans for a global pandemic. But governments were reluctant to allocate money and attention to prepare for something that seemed more like a nightmare from the past than an actual possibility.

Americans then and now were surprised by disease when perhaps they shouldn’t have been. To use a technical term, the diseases caught us with our pants down. They exposed gaps in our awareness of health risks, and they revealed a certain degree of hubris. In the heady aftermath of the Revolutionary War and in our era of modern technological marvels, Americans overestimated their control over the forces of nature.

Benjamin Rush, the most celebrated doctor in the early United States, believed that the American Revolution had ushered in a golden age, not only in politics, but in health as well. “All the doors and windows of the temple of nature have been thrown open by . . . the late American revolution,” he wrote in a 1789 manual for young physicians.

When the fever came to Philadelphia in 1793, Rush remained in the city for the duration, treating the sick with a “therapy” involving massive bloodlettings. Writing to his wife, a far humbler Rush praised God for his own preservation and remarked, “What a bitter thing must sin be to deserve even such a punishment as a destroying pestilence.”

Both outbreaks also disproportionately affected the poor and marginalized. The effects of COVID-19 have mirrored racial and economic disparities in the United States—throughout the pandemic, racial minorities and economically disadvantaged have been much more likely to get the disease and to die from it. According to one estimate, the 65 million Americans who receive Medicaid assistance have been more than four times more likely to die from complications of COVID-19. This is because impoverished Americans often lack access to healthcare, they are more likely to work in crowded workplaces without recourse to remote options, and they tend to have pre-existing health conditions at higher frequencies.

Very similar disparities existed in the early republic. The printer Mathew Carey wrote a popular account of the 1793 epidemic in which he estimated that seven-eighths of those who died were poor. Carey implausibly blamed bad hygiene and loose morals.

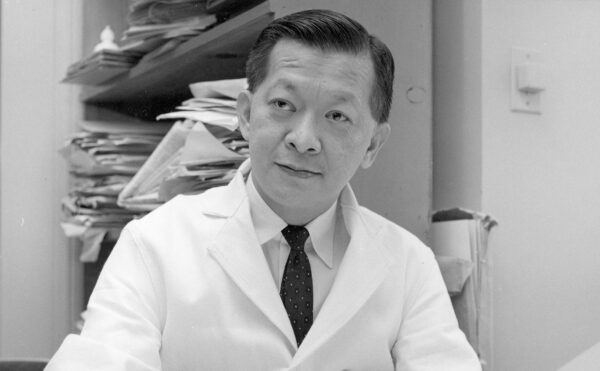

Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, leading figures in Philadelphia’s Black community, came much closer to the mark in their Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, during the Late Awful Calamity (1794). Written in reply to Carey, who accused Black nurses of theft and profiteering, the Narrative emphasized the heroism of Black volunteers and called attention to a simple truth: unlike the wealthy and middling classes who fled the city at the first sign of disease, the poor had no choice but to remain. They also tended to live in the more densely populated waterfront, right where newly arrived mosquitoes hungrily swarmed. Finally, then as now, access to healthcare cost money, which meant that impoverished victims of yellow fever could not avail themselves of the nursing care that was, and still is, the best way to treat yellow fever.

Left, Absalom Jones, portrait by Raphaelle Peale, 1810. Right, Richard Allen, lithograph by Albert Newsam, ca. 1850.

Both outbreaks also produced controversy—lots of it.

When yellow fever first struck, the nation’s doctors quickly divided into two schools of thought about its cause and prevention. One group, the localists, believed that yellow fever arose from the pestilential miasmas that emanated from dirt, decay, excrement, and all the other foul things that cities had to offer. They suggested that sanitary reform—essentially cleaning cities and supplying fresh drinking water—would solve the problem.

The other group, the contagionists, argued that yellow fever was imported by commercial vessels. They believed that quarantines and the regulation of trade would eradicate yellow fever from the ports. The acrimonious debate lasted for years, enveloping the public in a bitter feud that fractured trust in the medical community and exacerbated tensions in the young nation.

As it turns out, both sides were partially correct. Since A. aegypti prefers to breed in small, artificial containers of water—such as the rain barrels used to collect water in the 18th century—yellow fever was linked to urban conditions, as the localists insisted. At the same time, A. aegypti was a non-native species, and it died in the frosty mid-Atlantic winters; so the mosquitoes did have to be reimported each year before yellow fever could occur, as the contagionists claimed.

Engraving of the Delaware River waterfront in Philadelphia, 1800, by William Birch.

While doctors of our time have achieved something close to unanimity on questions about the cause and prevention of COVID-19, that hasn’t kept Americans from forming their own ideas and debating them fiercely in the vast marketplace of ideas. Most everything about the disease has been doggedly contested, from where it originated (The Wuhan wet market or the Wuhan Institute of Virology? From bats? Pangolins? From shadowy government organizations? The deep state?) to what we should do about it (Shut down? Stay open? Wear masks? Take ivermectin? Get vaccines?).

The existence of such debates isn’t particularly remarkable, but the fact that these debates fell clearly along political lines is.

In the time of COVID-19, Democrats have favored stiff lockdown measures, mask mandates, and universal vaccinations; they have openly celebrated the authority of science, encouraging others to do so as well. Republicans have been more critical of the lockdown’s severity, they have been more receptive to vaccine skepticism, and they have shown greater reluctance to believe the “experts.”

Pundits have posited many explanations for this disparity: the parties’ conflicting ideas about personal “liberty,” their different attitudes toward the roles of the state and science in daily life, their contrasting perceptions of the trustworthiness of news reporting and other sources of information, the economic costs of the shutdown, the president’s personal disdain for scientists and scientific knowledge, and the fact that the pandemic started during an unusually important and divisive election year.

In the 1790s, opinions about yellow fever also mapped strongly onto the political landscape, which was then polarized by the two political parties, the Federalists, whose informal leader was Alexander Hamilton, and the Republicans, whose informal leader was Thomas Jefferson. Those who have seen Hamilton may remember the basic tenets of the parties.

Federalists promoted a strong central government, whose institutions, such as the Bank of the United States, would take an active role in shaping a mighty manufacturing economy. In terms of foreign policy, they called for an alliance with Great Britain against France, mainly because the French Revolution was unfolding at the same time, and with the guillotine, the regicide, and all, things seemed to have gotten radically out of hand.

The Republicans favored a small government that would oversee a simple and virtuous agrarian republic. The Republicans feared that cities stimulated vice and corruption, and so they wanted to keep them few and small. In foreign affairs, they favored cooperation with France, their erstwhile ally in the Revolutionary War.

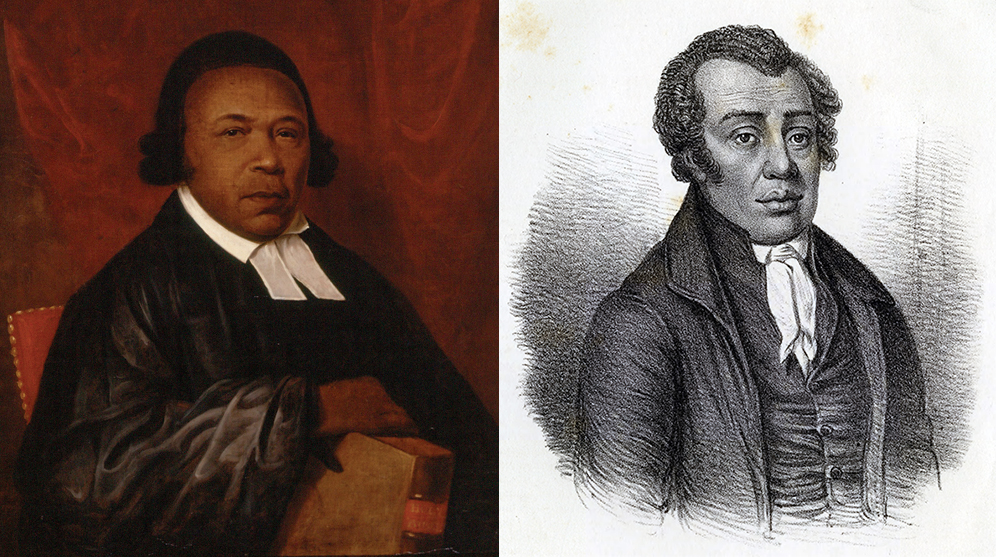

Detail of an unattributed political cartoon, based on newspaper accounts, lampooning the New York Board of Health for mistaking a man’s drunken condition for yellow fever, 1820.

What Hamilton doesn’t mention is that Federalists overwhelmingly tended to be contagionists and Republicans tended overwhelmingly to be localists. If we look at the implication of the medical theories, it isn’t hard to see why.

For the Federalists, quarantine measures fortuitously benefited both their domestic and foreign policy agendas. By limiting foreign trade, quarantine would protect the domestic manufacturing industry from foreign competition. Blaming foreign sources of contagion also happily exonerated cities from charges of unhealthfulness; this was important because manufacturing happens in cities. It also proved a convenient excuse for barring entry of the “radical” French and Haitian refugees, who were fleeing from the horrors of the French and Haitian revolutions. This same fear of outside French influence led the Federalists to pass the infamous Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798!

Republicans drew as much self-interest from the localist doctrine. For one, localism confirmed Republican suspicions that cities were indeed unhealthy places. Far better to farm in the salubrious air of the countryside. As Jefferson bluntly put it in a letter to Rush, “Yellow fever will discourage the growth of great cities in our nation, & I view great cities as pestilential to the morals, the health and the liberties of man.”

Localist sanitary reform would also leave foreign trade intact; thus, cheaply produced manufactured goods from abroad would continue to discourage domestic manufacturers. As for the refugees, Republicans were split. While many welcomed French and Haitian revolutionaries, slaveholders such as Jefferson didn’t want anyone talking too loudly of liberty.

The utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill once wrote, “Men who have been much taught . . . do not see, in the facts they are called upon to deal with, what is really there, but what they have been taught to expect.” Federalists and Republicans saw in yellow fever exactly what they wanted to see. And it is certainly true in our time that many have embraced beliefs about COVID-19 that suited their own economic and political ends.

The obliviousness to the real threat of disease, the disproportionate impact it had on the poor, and the way politics influenced the public’s understanding of disease—all are key features of the COVID-19 pandemic that were anticipated by yellow fever more than 200 years before.

Of course, those looking for differences will find them too. We are fortunate to have a medical and scientific community that agrees on the principles of disease cause and transmission, and we are fortunate to have moved on from therapeutic systems that involve draining blood.

But another difference should give us pause. While self-interested rationalization may have steered Federalists and Republicans to contagionism and localism respectively, at least they subscribed to sound theories that were supported by medical and scientific knowledge. For all our medical advantages, in our own time one partisan group has openly denied scientific knowledge and vilified its creators. That’s a precedent we all might come to lament.