As the judge banged the gavel, William Dampier hung his head in disgrace. One of the most celebrated scientists of his age was now a convicted felon.

It was June 1702, and because this was a British naval court, the lawyers and defendant had convened on the deck of a ship, the 55-yard-long, 100-gun HMS Royal Sovereign, then anchored off the southern coast of England near Spithead. A salty wind whipped the air as three dozen judges, including four admirals, considered the case. It focused on Dampier’s actions as captain during a recent voyage to Australia—an extraordinary mission that had begun with high hopes. Rather than trade or war, its main objective had been the gathering of plant and animal specimens and information about the distant continent. It was arguably the first scientific expedition in history.

But however noble the plan, the voyage had been cursed from the start, full of mistakes and mutiny. Dampier had struggled to even reach Australia, then had to abandon his mission after a disgraceful clash with an Indigenous group. On the way home he lost the Crown’s leaky ship to the sea—a final humiliation that culminated in his trial.

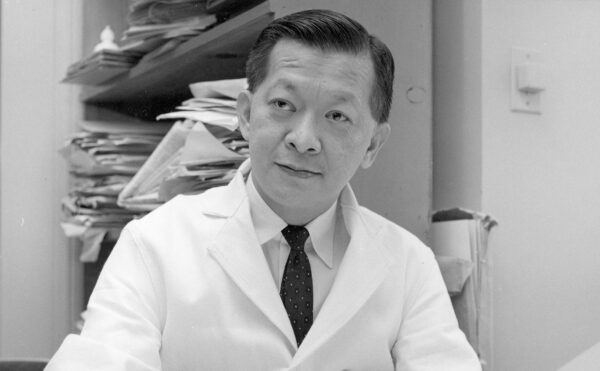

To be sure, most of the charges against Dampier had no chance of sticking. The murder claim was flimsy, and the accusations of incompetence were laughable: he was the best navigator alive, an expert on winds, currents, and weather. But as the trial progressed, Dampier sensed the court was determined to punish him somehow, for something. The 50-year-old captain, whose baggy eyes and long, limp hair cast a hangdog expression, braced for the worst. And so it was: the judges found him guilty of thrashing his lieutenant with a cane and declared him “not a fit person to be employed as commander of any of Her Majesty’s ships.” He was fined three years’ pay and dismissed from the navy.

Dampier staggered off the ship embittered and broken. He was the greatest naturalist of his day—so much so that Charles Darwin later counted himself a disciple. But whatever his brilliance, William Dampier would always be guilty of one thing in the eyes of the authorities. He would always be a pirate.

Dampier’s descent into piracy was perhaps inevitable. Although born relatively well off in Somerset in western England, he lost his father at age 7 and mother at age 14 and was plunged into poverty. After being apprenticed to a shipbuilder, he took to the sea, visiting Java and Newfoundland on merchant ships before an unhappy stint in the navy. He eventually sailed to the Caribbean in April 1674 at age 22 and became a logger. In his spare time, Dampier took long nature hikes and was thrilled to encounter creatures that he had only heard about in tall tales—porcupines and sloths, hummingbirds and armadillos. These treks awakened a love of natural history that would last his whole life.

His troubles started in June 1676, when a hurricane destroyed his logging camp and washed away his equipment—axes, saws, machetes. Loggers in that era had to provide their own tools, and Dampier had no money to buy more. So, as Dampier later wrote, “I was forced to range about to seek a subsistence.” This was a euphemism. “Ranging about” meant piracy. He joined a crew of ruffians and set sail.

At the time there were two distinct classes of pirates. Some were so-called privateers, who had tacit permission from their home governments to harass enemy ships. Privateering overall was tolerated if not respectable. Dampier, in contrast, was a buccaneer, and buccaneers had no permission to raid anyone. They were simple criminals, and their home governments scorned them as much as their enemies did. The buccaneering crew Dampier joined stood even lower than most, because instead of raiding ships full of luxuries, they often stormed pathetic little coastal camps, stealing from folks no better off than themselves.

Dampier and his crew spent the next several years waylaying ships and raiding settlements along Latin American coastlines. It’s not always clear what role Dampier played during these attacks. He recorded priests being stabbed, prisoners being tossed overboard, and Indigenous people being picked off with rifles or tortured for intelligence. And there is indirect evidence that he partook in at least some atrocities: once, during a fierce storm when he feared dying, Dampier looked back with “Horrour and Detestation on Actions which before I disliked, but now I trembled at the remembrance of.” He hadn’t been to confession in years, and scores of unnamed sins apparently weighed on his soul.

Every so often, Dampier’s crew made a decent score: gems, bolts of silk, a stock of cinnamon or musk. One time they seized eight tons of marmalade. More often the pirates struck out and spent the night outdoors with nothing but “the cold ground for our bedding and the spangled firmament for our covering.”

Dampier returned to England in 1678 and soon married a lady-in-waiting to a duchess. He had every intention of going straight and decided to return to the Caribbean with a load of trade goods. But his lust for new lands, new skies, new plants and animals, proved too strong. After a trip to Jamaica, he fell in among pirates again—against his will, he claimed—and took off. Ultimately, he “was well enough satisfied” wherever he ended up, he said, “knowing that the farther we went, the more Knowledge and Experience I should get, which was the main Thing that I regarded.”

After his Caribbean exploits, Dampier joined another pirate crew that lit out for territories in Southeast Asia. While there he became something of a proto-anthropologist, recording details about the cultures he encountered. And for his time, he proved remarkably open-minded. Whenever he saw a (to him) strange custom or rite, he strove to understand it. He later gave the first account in English of “ganga,” or marijuana (“Some it keeps sleepy, some merry, some putting them into a laughing fit, and others it makes mad”), and introduced dozens of new words into English, including banana, posse, smugglers, tortilla, avocado, cashews, and chopsticks. He described a mass circumcision of 12-year-olds in the Philippines, as well as tattooing in Polynesia.

Throughout these journeys Dampier took copious notes on everything he saw, stuffing them into bamboo tubes for safekeeping. When he finally returned to England in 1691, he began preparing a travelogue. A New Voyage Round the World appeared in 1697 and was a smash hit. Some historians even credit it with launching the entire genre of travel writing. After its publication, Dampier received an invitation to lecture at the prestigious Royal Society in London, the world’s premier scientific club. He also dined with several eminent statesmen, including diarist Samuel Pepys. The bigwigs wanted to talk natural history, of course, but some of them no doubt felt a frisson of pleasure in knowing they had a real-life pirate at their table.

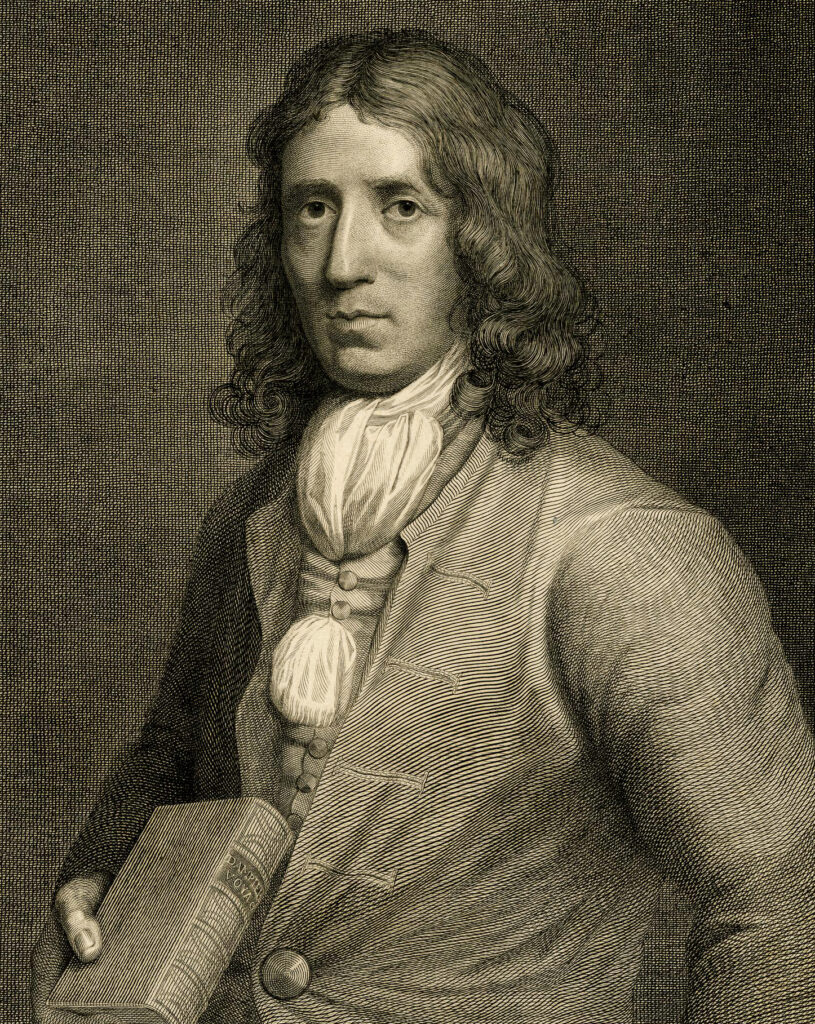

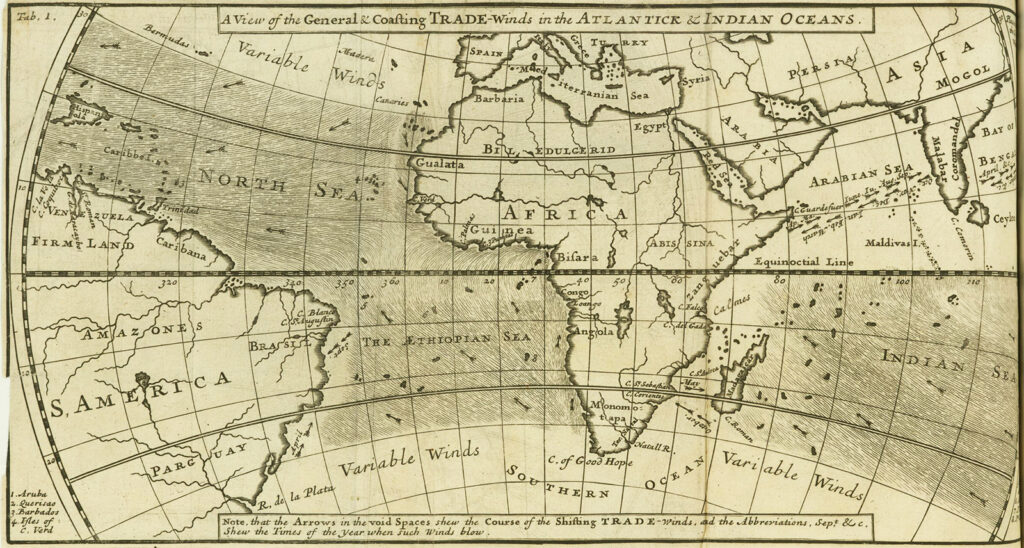

With the public clamoring for more, Dampier published a sequel to A New Voyage in 1699. It included his famous essay “A Discourse of Winds,” which later captains, such as James Cook and Horatio Nelson, considered the best practical guide to sailing they had ever read. The essay also greatly advanced the scientific study of winds and currents. Two of Dampier’s contemporaries, Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley (of comet fame), had recently published treatises on the origins of tides and rainstorms, respectively. Dampier’s essay nailed down where winds and currents come from. In one sweep, then, these three scientists solved several age-old mysteries about the sea and the cyclical movement of water around the globe. We normally wouldn’t include a pirate in the same company as Halley or Sir Isaac, but in this field, Dampier held his own.

Oddly, though, Dampier wasn’t in England to see his second book published. He had made very little money from the first one, in part because authors didn’t enjoy many copyright protections at the time; most of the book’s profits were scooped up, ironically enough, by literary pirates. Dampier still needed to earn a living somehow.

Moreover, he desperately wanted to leave piracy behind and reinvent himself as a respectable scientist. He jumped at an offer from the First Lord of the Admiralty to lead an expedition to Australia. Part of Dampier’s mission was to scout out commercial opportunities down under to help jump-start Great Britain’s colonial and imperial ambitions; these were the early days of the British Empire. But the main goal was to collect flora and fauna. It was unlike any mission the navy had ever undertaken. And with Dampier in charge, it was a disaster from the get-go.

Dampier had a curmudgeonly streak. He delighted in nature but grumbled about his fellow human beings. He could also be arrogant, especially when dealing with subordinates. It didn’t help matters that Dampier’s second-in-command on the Roebuck, a lieutenant named George Fisher, despised Dampier as pirate scum. Fisher swore up and down that Dampier was plotting to commandeer the ship and go privateering as soon as they hit open water.

The Roebuck set sail in January 1699. Even before it reached its first stop—the Canary Islands, to stock up on brandy and wine—Dampier and Fisher were quarreling. As one witness reported in blunt sailor speech, Fisher “gave the captain very reproachful words and bade him kiss his arse and said he did not care a turd for him.”

Those tensions erupted into violence in mid-March. It started with a keg of beer. Nautical tradition held that a keg be tapped when a ship first crossed the equator, allowing men to blow off steam in the torrid weather. Dampier’s crew ran through their keg a little too quickly, though, and begged Fisher to let them tap a second. Instead of consulting Dampier, as navy regulations required, Fisher gave assent alone.

To most captains, this might have been a forgivable offense. But Dampier was already on edge: rumors were swirling that Fisher planned to heave him overboard to feed the sharks. And on seeing the second keg open, Dampier lost it. He grabbed his cane and confronted Fisher, demanding to know why he had tapped the keg. Before Fisher could answer, Dampier clubbed him and proceeded to beat him bloody. He then clapped Fisher in leg irons and confined him to a locked cabin for two weeks. Fisher couldn’t leave even to use the head; he was left to stew in his own filth.

The crew stopped in Brazil for a few weeks, where Dampier had Fisher jailed. And the moment his cell door clinked shut, Fisher climbed up to his window and began yelling to passersby in the street, railing about his imprisonment and slandering Dampier left, right, and sideways. He later composed letters to authorities in England to expose the pirate-scientist as a tyrant. Fisher’s every waking thought was to destroy Dampier.

While Fisher plotted, Dampier disappeared into the bush around Bahia, Brazil, taking notes on indigo and other crops the British would later use to build their colonial empire. One observation during this time stands out for its scientific and historical importance. After observing some flocks of “long-legg’d fowls” at different sites, Dampier realized that, while each flock was distinct, no one group was distinct enough to count as its own species. There was a continuum of variation. So he coined a new word, sub-species, to describe this phenomenon. He was groping toward an idea—about variation in nature and the relationships among species—that his admirer Darwin would later run with in On the Origin of Species.

Dampier eventually shipped Fisher back to England—where, Dampier assumed, there would be a humiliating trial for insubordination. Dampier was only half right. There would be a trial and humiliations aplenty, just not for Fisher.

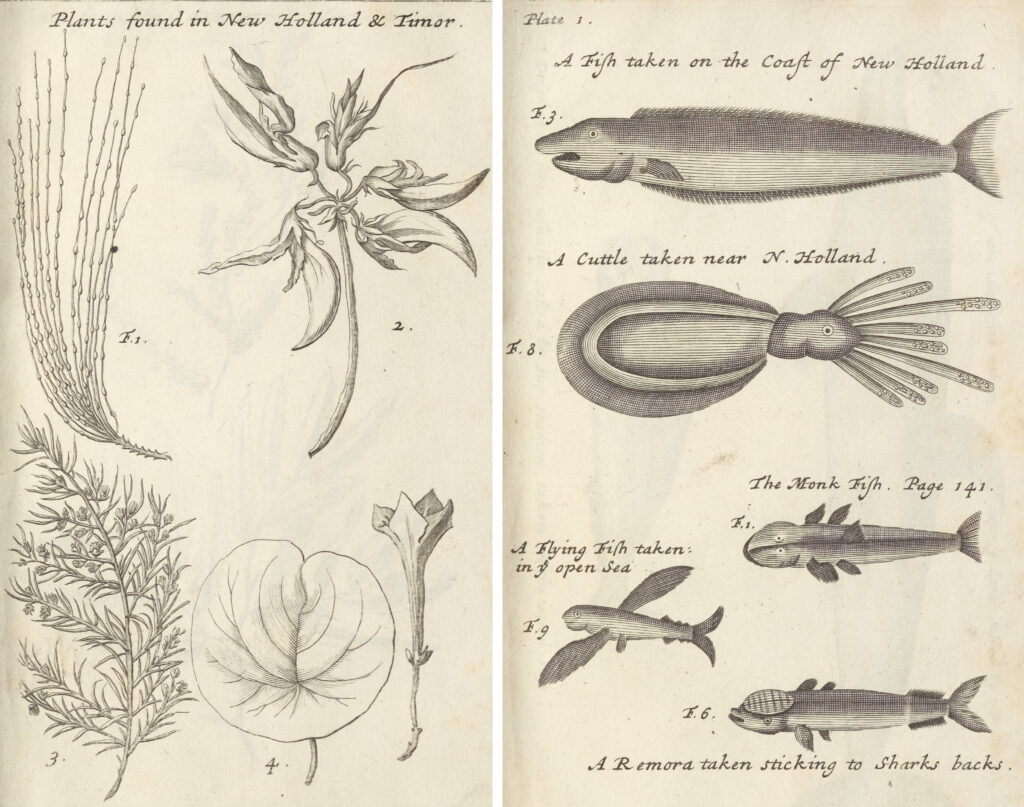

With Fisher absent, however, tensions cooled on the Roebuck, and by mid-August the crew reached western Australia, landing on the gleaming white beaches of what Dampier, for good reason, named Shark Bay. They spent the next few weeks observing dingoes, sea serpents, humpback whales, and more—a brilliant start to their scientific-imperialist campaign.

Their luck didn’t hold. Northwest Australia is arid, and despite scouring the coast, the Roebuck could not find a source of fresh water. The thirsty sailors tried approaching some Aboriginal people, whom they assumed had tricks for finding water. (Indigenous Australians did have such tricks, including tracking birds and frogs and hacking at tree roots.) But whenever the sailors came near, the locals scattered. So Dampier came up with a desperate plan.

After creeping ashore, he and two companions hid behind a sand dune to ambush the locals. The plan was to kidnap one and force him to lead them to a spring. When the Englishmen jumped out, the locals once again ran, and the sailors gave chase—not realizing they were falling into a trap. As soon as Dampier and company were exposed on open ground, the Australians wheeled and attacked with spears. One of Dampier’s men was slashed in the face; Dampier himself was nearly impaled. When warning shots failed to drive the locals back, Dampier took aim and wounded one with his pistol. It’s a rare moment in his books where he admits to violence.

Given Dampier’s earlier comments, this assault probably shouldn’t come as a surprise. He had visited Australia before, and despite his magnanimity toward most cultures, he had dismissed Indigenous Australians in his 1697 book as the “miserablest People in the World,” adding that “they differ little from brutes.” Some scholars have argued that Dampier’s publishers added those words to sensationalize his voyages and goose sales; Dampier’s original journals are less harsh. Regardless, Dampier knew that the ambush on the Roebuck voyage was unforgivable, calling himself “very sorry for what had happened.”

Dawn Casey, an Aboriginal woman who formerly served as the director of the National Museum of Australia and the Western Australian Museum, has harder words for Dampier, citing the role his racist language played in setting the tone for the colonization of Australia. “Dampier, Joseph Banks, Captain James Cook and those governors that came after them who employed academics and anthropologists, have certainly, no doubt, set the tone and the blueprint for Aboriginal Australia.” The attack also foreshadowed centuries of ugly clashes between white Europeans and Indigenous Australians, the fallout of which Australia is still dealing with in multiple forms.

The parched crew slunk away from Australia after the attack, and things only got worse from there. Dampier tried to salvage the voyage by exploring and collecting specimens in New Guinea. But the British navy hadn’t exactly handed him its trustiest ship in the Roebuck. Its hull leaked and was infested with shipworms, and it soon got so creaky that Dampier had to turn tail and make a run for England. But on the shores of Ascension Island in the Atlantic tropics, the Roebuck sprung a massive leak. Fearing he would be blamed for its demise, Dampier tried plugging the hole with anything he could think of, including a side of beef and his personal pajamas. Both stopgaps failed. The crew abandoned ship at Ascension, and Dampier lost virtually every specimen he had gathered. The men spent five weeks watching other ships sail blithely by in the distance until a flotilla finally pulled in and rescued them.

Returning to London without a ship or specimens was bad enough. But when Dampier arrived in August 1701, he found that George Fisher had been poisoning English society against him—damning him in such lusty terms that the admiralty felt obliged to court-martial Dampier and try him in June of the following year.

To their credit, the judges dismissed most of the charges against Dampier, including one that he had murdered a querulous crew member by locking him into a cabin for a spell. (The man actually died 10 months after the punishment ended.) But the judges could not abide the caning of Fisher, a fellow officer, and they found Dampier guilty of “very hard and cruel usage” of his second-in-command.

Dampier had tried to turn respectable, and it had profited him nothing. He was as penniless as ever and more of a pariah than ever. He had only one option left: the 50-year-old naturalist returned to piracy.

In 1703, Dampier caught a break. A war with Spain and France had broken out, and England sought out pirates to harass the enemy. Though he was barred from commanding her ships, Queen Anne summoned the 51-year-old pirate for an audience. Dampier kissed the royal hand and soon received a commission to captain a private vessel named St. George.

Alas, the voyage of St. George was another messy, mutinous affair. Dampier’s men accused him of accepting silver dinnerware and other bribes from captains of the ships he captured. In exchange, Dampier would conduct only a superficial search of their holds and let them sail away with most of their treasure intact. Rumor also held that Dampier was drinking heavily. When the voyage ended in 1707, Dampier’s reputation as a captain was in shambles, and he never commanded another ship. He died, poor and obscure, in 1715.

Despite his rough last years, Dampier’s legacy improved considerably after his death. Jonathan Swift poached his stories for Gulliver’s Travels, as did Samuel Taylor Coleridge for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Dampier’s most influential fan, Charles Darwin, even brought Dampier’s books along on his formative Beagle voyage in the 1830s. Darwin studied Dampier’s descriptions of species and pored over his accounts, effectively using Dampier as a guide. Darwin might never have become Darwin without Dampier.

But while adventure writers and scientists have ignored Dampier’s sins, latter-day George Fishers have found him harder to abide. When Dampier’s hometown in England discussed putting up a plaque to honor him in the early 1900s, one God-fearing fellow stood up and damned him as “a pirate ruffian that ought to have been hung [sic].” Critics nowadays go even further. They contend that Dampier’s science, however groundbreaking, merely blazed a trail for colonialism and its brutalities. His natural-history raids also arguably paved the way for biopiracy—the cavalier theft of natural resources from developing countries.

The thing is, both sides have a point. Dampier was lowdown and brilliant, inspiring and unscrupulous. His work advanced nearly every scientific field that existed at the time—navigation, zoology, botany, meteorology—and he did despicable things in the meantime. As one biographer noted, the likes of Darwin and Swift “owed much more to Dampier than a single model. It can in truth be said that they owed the entire spirit of a new age to this one man.” That new spirit included many good things, and many ugly ones as well.