On Valentine’s Day 2016, I found myself far from home. There would be no romantic meal with my lovely wife that year. Instead I huddled with my boss while we sat anxiously in the windowless, subterranean meeting room of a Pasadena hotel. We had arrived at the California Antiquarian Book Fair the previous day, and now we were waiting for an auction of rare books and manuscripts to begin.

Some desirable items had been assembled for the auction, including a first edition On the Origin of Species, an author’s presentation copy of Ulysses, and an official pilot’s log of the Enola Gay. There were also some artifacts up for bid, notably Kary Mullis’s 1993 Nobel Prize medal for the invention of the polymerase chain reaction (at $665,000, it would fetch the most of any lot by far), and—bizarrely—Muhammad Ali’s carved bone-and-ivory cane that he sported in Zaire when he faced George Foreman in the famous Rumble in the Jungle in 1974.

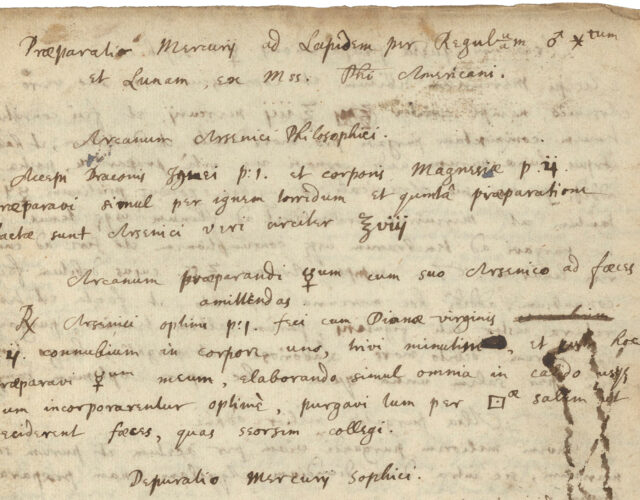

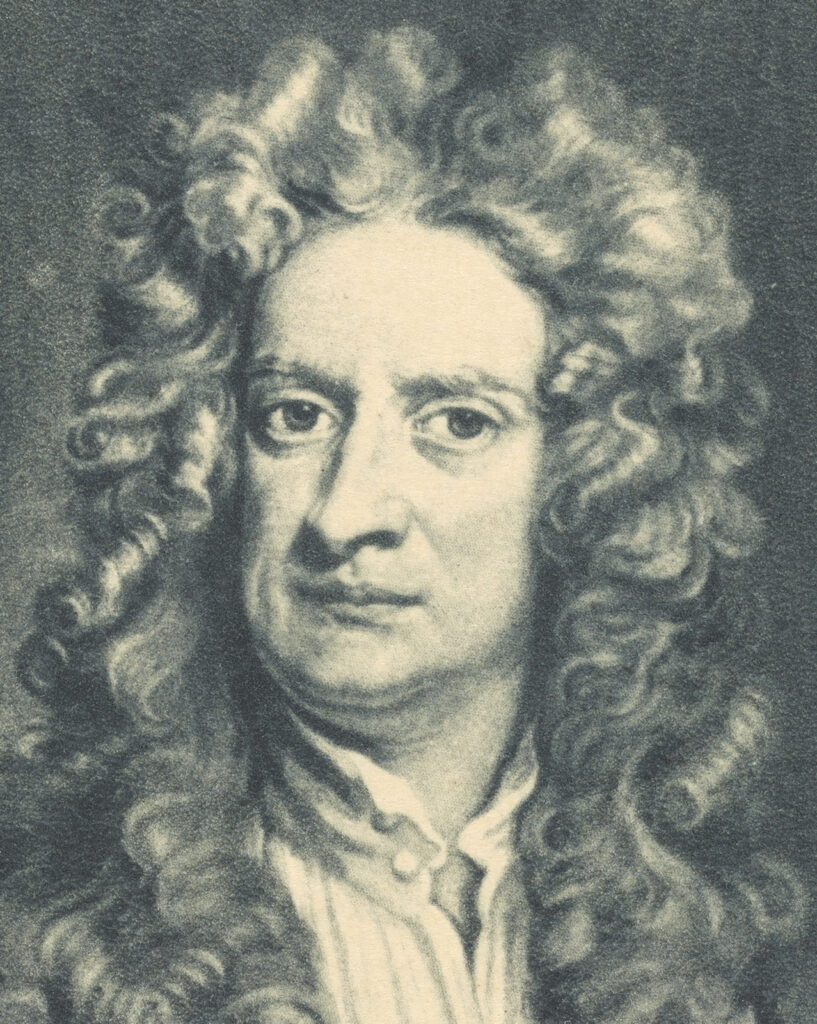

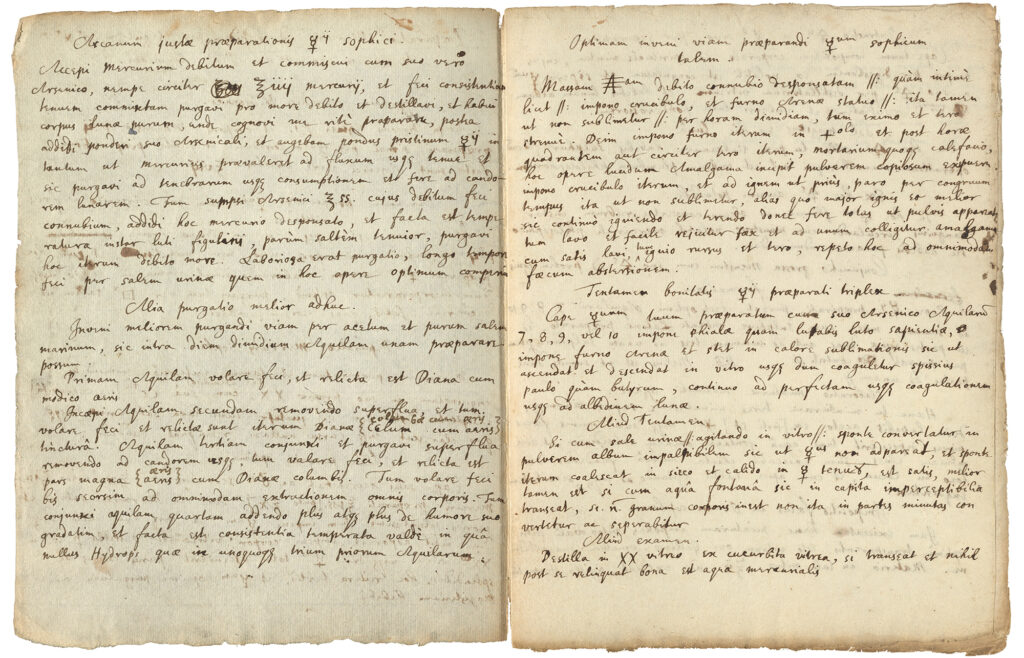

My quarry was a rare autograph alchemical manuscript in the hand of Isaac Newton—a set of instructions for making the philosophers’ stone by his favorite alchemical author, Eirenaeus Philalethes, whom he referred to by the sobriquet “the American Philosopher.” It was one of a steadily shrinking number of the great scientist’s personal papers not yet in institutional hands, and it would make an excellent addition to the Science History Institute’s Othmer Library of Chemical History.

It was at another auction, 80 years earlier, that Newton’s papers first burst into public view.

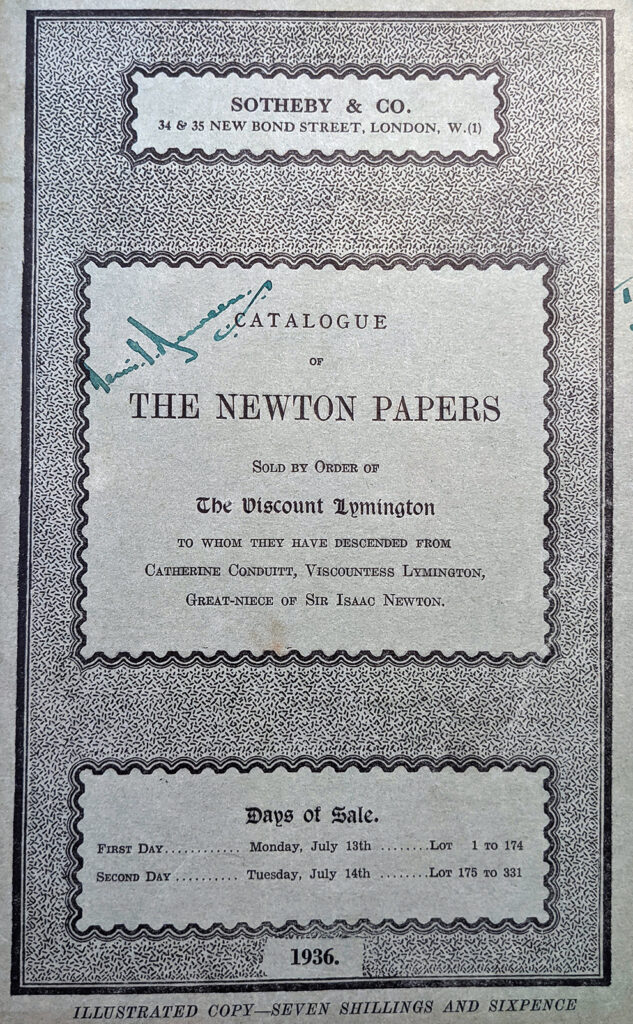

In 1936 Gerard Wallop, Viscount Lymington, found himself in a bind. In the wake of a ruinous public divorce and faced with death duties of £300,000 on the estate of his aunt (the widow of the sixth Earl of Portsmouth), Wallop was forced to sell the family’s ancestral seat, Hurstbourne Park, along with some of the patrimony held there, including the manuscripts of his illustrious forebear, Isaac Newton. The papers were sent to Sotheby’s, where they were auctioned off over two days, on July 13 and 14.

Only a handful of people had seen the papers since Newton’s death, in 1727. Newton had been orderly in his arrangements, and in the weeks leading up to his death had destroyed some papers. But, oddly, he left no will nor any provision for the manuscripts he left behind.

Sarah Dry, who has written about the fate of these papers, believes this was on purpose: “Evidently Newton believed that what they contained was important, too important to be lost, but also too dangerous to publish right away.” For what they contained beyond the mathematical and scientific material one would expect were reams of notes on alchemy, church history, and Newton’s plainly heretical theological beliefs.

As for the heresy, briefly put, Newton was an Arian: he had concluded from his voracious study of scripture and the writings of the early church fathers that the concept of the Holy Trinity was a monstrous perversion of true Christianity.

His alchemical papers—largely reading notes, many couched in florid, impenetrable metaphors—were likewise bewildering. Newton had spent a lifetime absorbed in this study, which the impending Enlightenment would discredit.

While Newton’s alchemical interests might have marred his reputation, his heretical beliefs would have had dire consequences during his lifetime, and his heirs were certainly not interested in making them known after his death. However, they did hope to capitalize on anything of value in the papers. And, indeed, some material was ready for publication.

Newton had been putting the finishing touches on his book The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended just days before his death. It was published posthumously in London in 1728. (The Othmer Library holds a Dublin edition published the same year.) The heirs commissioned Thomas Pellet, a member of the Royal Society, to go through the papers to find anything else worthy of publication. Pellet identified five candidates—the rest he labeled “Not fit to be printed.” In the end, only three saw light before the 20th century.

Anyone who has worked with these manuscripts must have sympathy for Pellet. They are a mess.

Newton frequently took a full sheet of paper about the size of a placemat, folded it twice, and slit one of the folds to make a little pamphlet of four leaves. Sometimes he would write on these pamphlets in an orderly fashion. But at other times, after beginning on one side and writing a few pages, he would later pick up the pamphlet and write something unrelated from the blank back toward the middle. Indeed, the manuscript at auction in Pasadena has an orderly Latin text starting from the front side and an unrelated English recipe written on the blank back side.

Sometimes Newton did the same thing but on a single page: he would write down from the top of the page then later turn the page around and write down from the top toward the now upside-down text at the bottom. Sometimes he struck through whole paragraphs of text, then carefully wrote a new paragraph between the lines of the struck-through text. Add in the fact that Newton sometimes drafted, redrafted, and re-redrafted the same text, and then—possibly decades later—scribbled completely unrelated material on the same sheet.

Needless to say, making sense of the manuscripts is a challenging task.

Newton’s half-niece Catherine Conduitt and her husband, John, a close associate of Newton’s, took the “unfit” manuscripts with an eye toward their preservation and perhaps as the basis for a biography, which never materialized. Their daughter married John Wallop, Viscount Lymington, son of the Earl of Portsmouth, in 1740, and the manuscripts fell into the hands of the earls of Portsmouth, who would hold them for nearly two centuries. During these years, the manuscripts were seen by almost no one. The earls were reluctant to allow anyone access to the materials, and from the testimony of those who did wheedle their way in, one gets the impression that the manuscripts lay undisturbed in their disarray for decades—even generations—on end.

There was one well-meaning attempt to make the manuscripts more accessible to researchers. In 1872 Isaac Newton Wallop, fifth Earl of Portsmouth, offered to donate the scientific papers held by the family to the University of Cambridge, where Newton had studied and taught. But for that to happen, some sense had to be made of the mass of papers, which had never been properly sorted since Thomas Pellet worked through them 145 years earlier. The earl turned the vast majority of the family’s manuscripts over to the university for sorting with the understanding that scientific or mathematical material would be donated to the university, and personal papers would be returned.

Anyone who has worked with these manuscripts must have sympathy for Pellet. They are a mess.

The sorting effort was spearheaded by two intellectual heirs of Newton, mathematical physicists George Gabriel Stokes and John Couch Adams.

Stokes was Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, a chair held by Newton before him and later by Stephen Hawking in the 20th century.

Adams is remembered today mostly for having mathematically predicted the existence of Neptune on the basis of perturbations in Uranus’s orbit. But Adams failed to have the prediction verified through observation, which allowed French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier—who undertook a similar calculation—to scoop him and gain credit for the discovery. (British astronomers are still sore about the blunder.)

Needless to say, these two would have found much of interest in Newton’s mathematical and physical papers and would have been equally stumped by his theological and alchemical writings. Despite the help of other experts, the sorting work proceeded at a glacial pace—it took 16 years to produce A Catalogue of the Portsmouth Collection of Books and Papers Written by or Belonging to Sir Isaac Newton, The Scientific Portion of Which Has Been Presented by the Earl of Portsmouth to the University of Cambridge. Drawn up by the Syndicate Appointed the 6th November, 1872.

While a few bits of alchemical material ended up in Cambridge’s possession, the vast majority was returned to the earl along with Newton’s theological writing and deemed equally unscientific. The papers would languish at Hurstbourne Park for nearly another half century—until Gerard Wallop fell on hard times.

The Sotheby’s sale in 1936 was hardly a spectacular success for the strapped Viscount Lymington. Most of the bidding came from the usual suspects, representatives of the London rare book trade who shared a mutual interest in keeping prices low.

A few of the lots were purchased by Pickering & Chatto, one of London’s oldest booksellers. Among those were three Newton manuscripts that eventually came to be in the collection of the Othmer Library in 2004. Thirteen of the lots were purchased by the French dealer Emmanuel Fabius and remained unseen in his collection until his death, in 1984. Among those papers was the manuscript that lured me to Pasadena decades later.

The most notable oddity at Sotheby’s was the presence of economist John Maynard Keynes, who showed up late on the first day and began bidding in earnest only on the second. At the sale, and in a fevered pursuit during the weeks and months afterward, Keynes amassed one of the most important collections of Newton’s alchemical papers, which he bequeathed to Kings College, Cambridge on his death, in 1946.

Others caught the Newton bug. Financier Roger Babson—who literally believed financial markets followed Newton’s laws of action and reaction and used the theory to predict a “terrific” crash in September 1929—also collected a significant amount of Newtoniana, including many manuscripts. (These resided for many years at Babson College, outside Boston, but eventually the incongruity of a small business school holding a world-class research collection of Newton material led to their relocation, first to the Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology at MIT, and then to the Huntington Library in California.)

Others have collected Newton’s papers with more dubious intent. A number of manuscripts went up for auction in November 2019, part of a large sale of Les Collections Aristophil. The enormous Aristophil collection, the brainchild of French dealer Gérard Lhéritier, was a cultural movement cum investment scheme in which shares of the manuscript collection were sold off to individual investors. Eighteen thousand people plowed roughly $1 billion into the operation, which included a swanky Museum of Letters and Manuscripts in downtown Paris. Unfortunately, it was all a scam.

The manuscripts were genuine, but their valuation was grossly inflated when broken into shares. When French investigators looked into Lhéritier’s books, they concluded that the massive enterprise was nothing more than an old-fashioned Ponzi scheme. Lhéritier was dubbed the Madoff of France. He was arrested, and the entire collection of 136,000 items was liquidated for pennies on the dollar. According to the New York Times, at the peak of his activity Lhéritier accounted for an estimated 5% of the global trade in rare books and manuscripts. This heavy-handed buying distorted the market, inflating prices and shutting out other buyers at auction.

Luckily, the Aristophil scheme collapsed in 2014, two years before my encounter with the Newton manuscript in Pasadena. Had the Madoff of France still been wheeling and dealing, we might not have had a chance.

The rare book market is not transparent. Collectors value their privacy and anonymity, and it is the exception rather than the rule to know whom a book is being sold by and to whom it ends up going. Instead, like Ahab we inhabit the surface of a vast, unknown sea awaiting the appearance of our quarry, which rises unpredictably and vanishes again equally so. After spending nearly 50 years in Fabius’s hands, the manuscript I was after in Pasadena had surfaced at auction in 2004, then vanished again, and may well have changed hands in private sales in the interim.

Our interest in this particular manuscript was its association with the work of “the American Philosopher,” George Starkey. He was probably Newton’s favorite alchemical author and wrote under the pseudonym Eirenaeus Philalethes, meaning “a peaceful lover of truth.”

Starkey was born the son of a Scottish minister in Bermuda, and after the death of his father was shipped to New England to finish his education. He graduated from Harvard College in 1646 and practiced medicine around Boston before emigrating to London in 1650. After a few fits and starts he became a successful chemical practitioner and alchemical author. He moved in the nascent scientific circles of 17th-century London and worked closely with Robert Boyle. He also began circulating the manuscripts of an American alchemical adept of his acquaintance. No one connected the dots between these two identities until the 20th century.

The Philalethes tracts were widely circulated and printed in a number of languages, as were Starkey’s works published under his own name. In this way, he became the first famous American scientist. Taking into account Starkey’s nationality, his importance in the history of alchemy, our setting in historic Philadelphia, and the connection to the philosophers’ stone, getting this manuscript into our collection became an institutional priority.

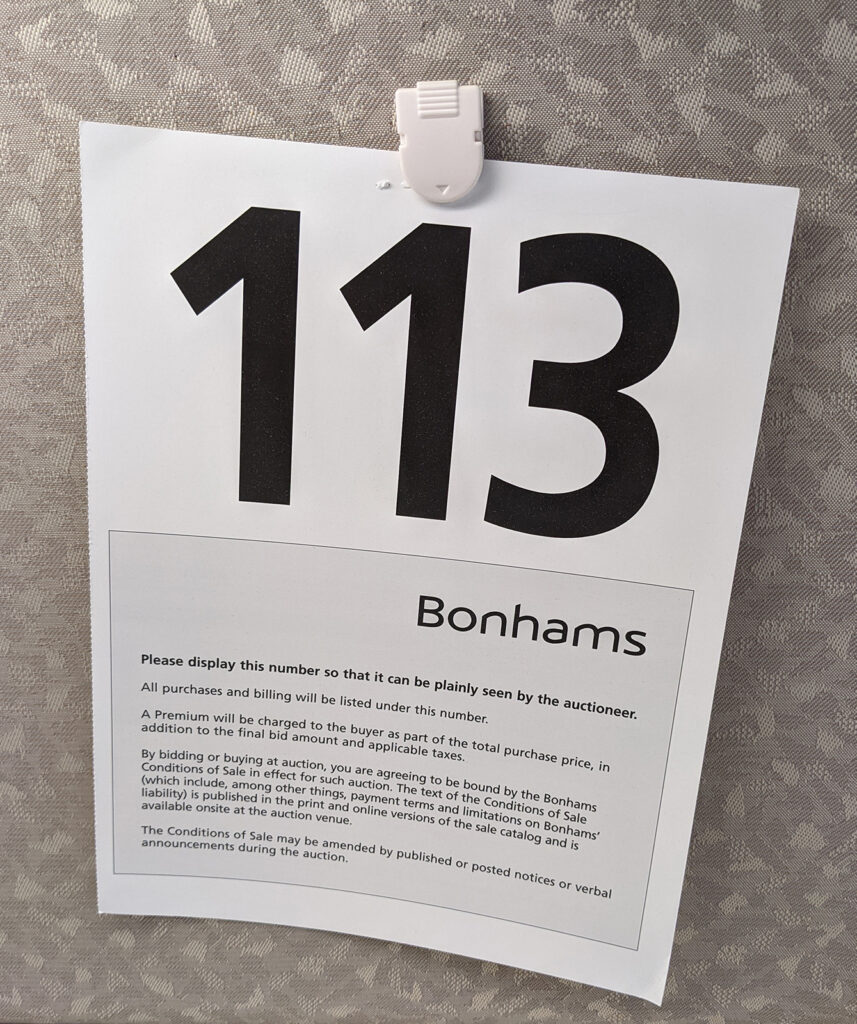

The staff at Bonhams auction house were expecting us in Pasadena. Ron Brashear, director of the Othmer Library, and I were both registered bidders. I suppose that way if one of us were absent the other could step in. Or if one of us fainted during the bidding, the other could carry on. The only danger with this arrangement was that in the excitement we might end up bidding against one another.

I was issued paddle number 113, a not very auspicious number, I thought. It’s not actually a paddle but a stiff letter-sized card that you hold up to identify yourself to the auctioneer at the conclusion of bidding. You’re supposed to hand them back at the end of the auction but in the excitement I forgot, and the Bonhams paddle now decorates my office.

I’ve bid in person at several auctions, and it is uncomfortably like those scenes you see in movies where the person scratches their nose and ends up bidding on a Picasso in the process. You make your first bid clear by raising a hand, but once the auctioneer knows you’re in, eye contact and a slight inclination of the head is all you need to commit yourself to the next highest bid.

With the Starkey manuscript at stake, I wanted my intentions absolutely clear, so I waved my hands around like a newbie. After our lot was over, I was so worried about bidding on something else by mistake that I sat on my hands and pointedly stared off into space over the auctioneer’s right shoulder, waiting for the auction to end. I don’t even remember how much Muhammad Ali’s cane went for. Our competition, it turned out, was not in the room but bidding by telephone. A bank of Bonhams employees to my left represented the telephone bidders, one of whom got in the initial bid. I raised my hand. It went back to the phone. I gritted my teeth and raised my hand again—I would be out of it in about two or three more bids. I waited. Nothing. Going once, going twice . . . . (They rarely say that, but I don’t remember the auctioneer’s actual patter that day.) We had it.

The manuscript, “Praeparatio Mercurii ad Lapidem per Regulum Martis Antimoniatum Stellatum et Lunam ex Manuscriptis Philosophi Americani” or “The Preparation of the [Sophick] Mercury for the [Philosophers’] Stone by the Antimonial Stellate Regulus of Mars and Luna from the Manuscripts of the American Philosopher,” is now ensconced in the rare book room at the Science History Institute and is available for scholars conducting research. More conveniently, it is available online in the Institute’s digital collection, where anyone from anywhere in the world can access it in high resolution.

When the Newton papers went to auction in 1936, the field of history of science was in its infancy. Those who attended the sale couldn’t make much more sense of the manuscripts than Newton’s heirs. For many buyers the papers’ value was intelligible mostly as autographs, relics of the legendary scientist.

Much of the history of science at the time was written by scientists who dabbled in the history of their disciplines. For chemistry, this fact was particularly problematic. Not only had transmutational alchemy long been discredited and dismissed by the field, the 18th-century chemical revolution of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier established the immutability of elements as a foundational paradigm. Therefore, whatever alchemists in the 17th century thought they were doing was clearly impossible and, given the impenetrable coded language and bizarre metaphors and imagery, probably insane.

When the Newton papers went to auction in 1936, the field of history of science was in its infancy. Those who attended the sale couldn’t make much more sense of the manuscripts than Newton’s heirs.

Indeed, much of the early scholarship on alchemy was done not by historians of science but by Jungian psychoanalysts. A now classic expression of this dismissal of alchemy was made by historian Herbert Butterfield in The Origins of Modern Science in 1949:

In the generations since, historians of science have become, if not adepts, at least adept at understanding alchemy for what it was.

For one thing, they have taken alchemists’ tangible interactions with the physical world seriously. Alchemists were able to do a wide range of impressive chemical feats. They were the first to make high molar mineral acids, such as oil of vitriol (sulfuric acid), aqua fortis (nitric acid), and spirit of salt (hydrochloric acid). They could separate the metals in alloys, such as extracting the gold from native silver, a profitable process for silver miners. They isolated phosphorus. (Newton’s recipe begins memorably, “Take of urin one barrel.”) Historians have learned a great deal from replicating the recipes and procedures found in alchemical texts in the modern laboratory.

But furthermore, by sympathetically investigating alchemical theory, scholars have come to understand how alchemists thought matter was constituted and how they conceived—for instance—that one metal could be turned into another.

Finally, historians of science have come to appreciate the culture of alchemy, the complex literary techniques that were (and remain) impenetrable to the uninitiated, and the interplay in producing texts intended both to reveal and obfuscate.

Those papers of Isaac Newton, in which he toiled to penetrate the arcana of alchemy, are at last beginning to yield insights into his alchemical endeavors and thought. Though they lay inaccessible for generations, the time has now come to bring them into the light.