Only a small proportion of the population has so far been vaccinated for COVID-19, and the long-term efficacy of the vaccines is still unknown. Nevertheless, a hodgepodge of entrepreneurs, airline and technology companies, international trade organizations, and government ministries are rushing to create virtual certificates that can confirm a vaccination or a negative test for COVID-19.

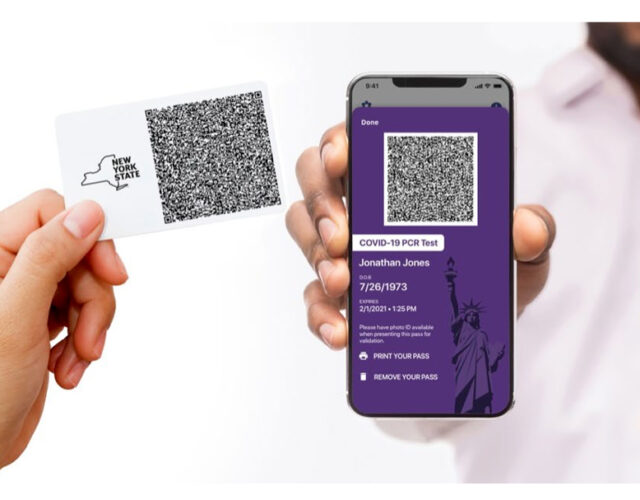

In general, the platforms work like this: people download an app on their phone, and they or their doctors upload confirmation of their vaccination or negative test results to these apps. If these new formats can be made consistent and worthy of trust, authorities and businesses could then use these digital health passports to decide who can enter a country, fly on a plane, attend school, enter a sports arena, or even eat at a restaurant. In February Israel rolled out its so-called green pass, which gives holders exclusive access to gyms, hotels, entertainment venues, and, as soon as this week, bars and indoor dining. Recently the European Union announced intentions to issue its own COVID-19 passport, and New York has begun testing its Excelsior Pass at sports arenas.

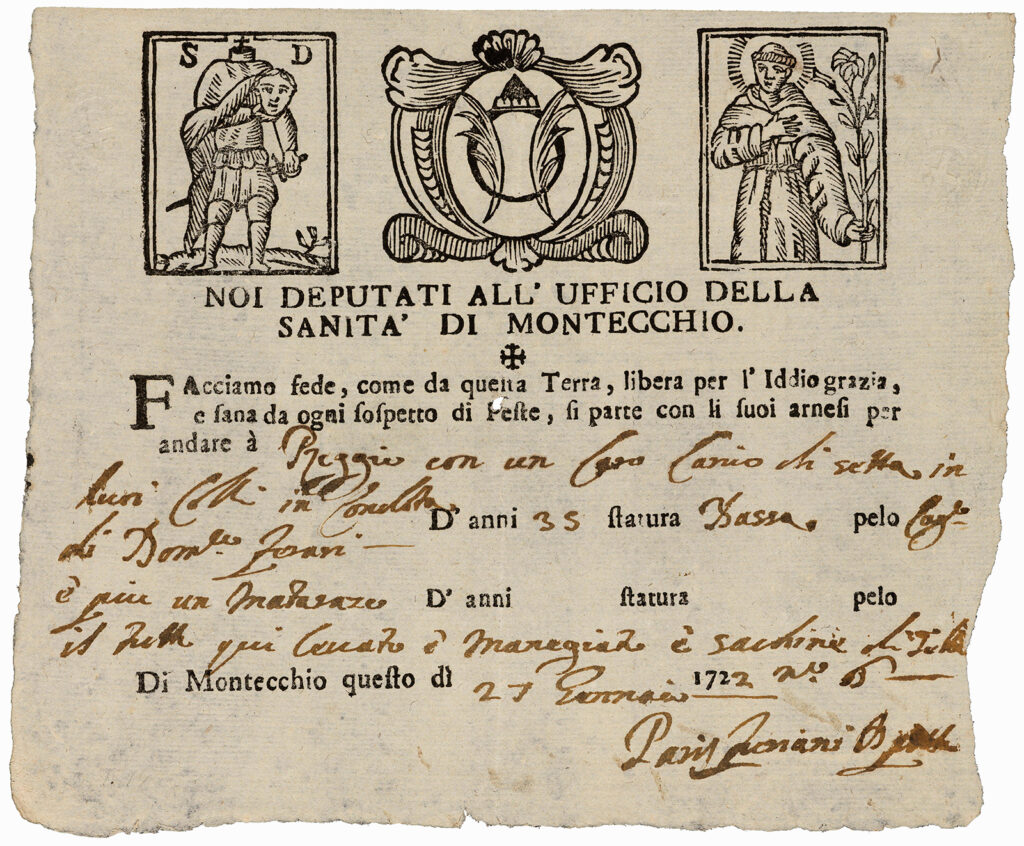

While such schemes have raised widespread criticism, the idea is both simple and old. Travelers have been using passes like these for about 600 years. In Europe, health passes—sometimes called health passports or certificates of health—became popular following the upheavals caused by the Black Death in the 14th century.

Health passes were produced for immediate use and were rarely saved. Only a miniscule portion of these once-common items remains. But enough examples exist to show that their core features have changed little over the centuries, even as medicine, public health, and government have seen revolutions. I estimate that as many as a few hundred thousand were issued before 1900, while in the 20th century individual passes probably numbered in the hundreds of millions.

Historian Alexandra Bamji has analyzed more than 200 passes dating from the late 15th to the early 19th century. Two essential components have persisted over time. First is the document’s authenticity, a way to confirm that the pass was truly issued to the bearer. Second is the certification by an authority that the bearer has been examined and poses no health risks to other jurisdictions. The origin of the word certificate combines certus, Latin for sure or true, with facere, meaning to make. A certificate of health makes a trustworthy confirmation of a person’s health status, backed up by symbols of the issuing authority.

The appearance of health passes, though, has changed over the centuries. Originally, they were handwritten by scribes or notaries. After the invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century, basic information could be printed, with individual details added by hand to each certificate. Limitations on access to printing technology and the inclusion of official signatures and seals conveyed that a pass was truly issued by a trustworthy authority.

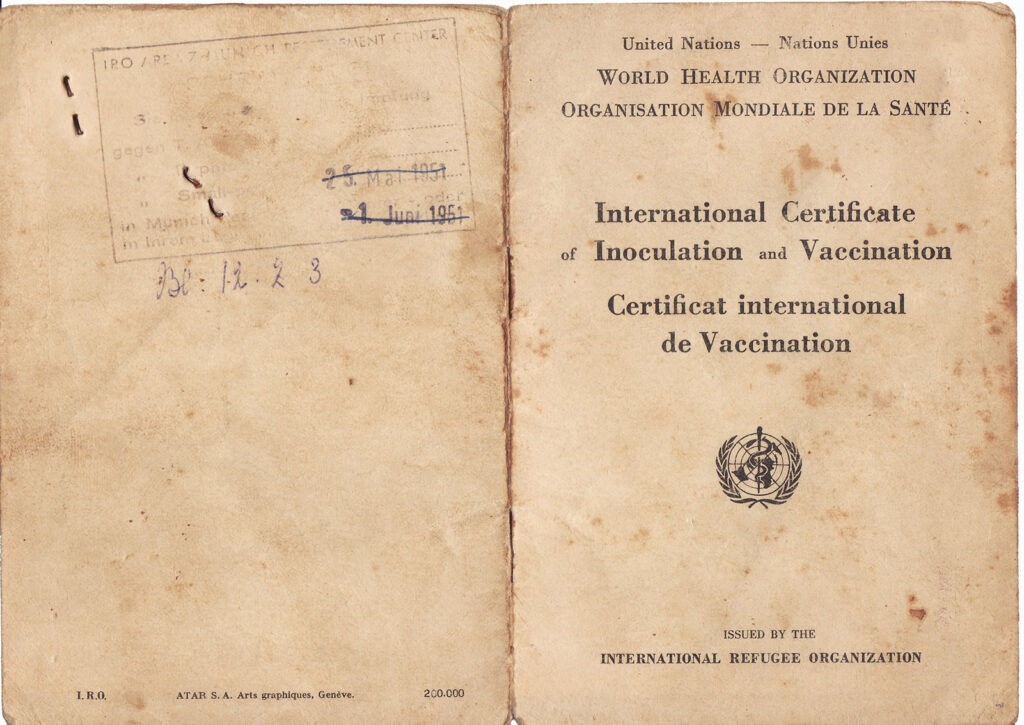

In more recent times, authenticating a person’s vaccination status was often the job of individual physicians, who were supported by an administrative apparatus that might be as small as a municipal health department or as large as the United Nations. Before smallpox was eliminated in the late 1970s, international travelers carried the World Health Organization’s “yellow card,” a small, stapled booklet presented along with a passport when crossing borders. The card’s initial focus was smallpox, but it remained in use to confirm vaccination for yellow fever and other infectious diseases.

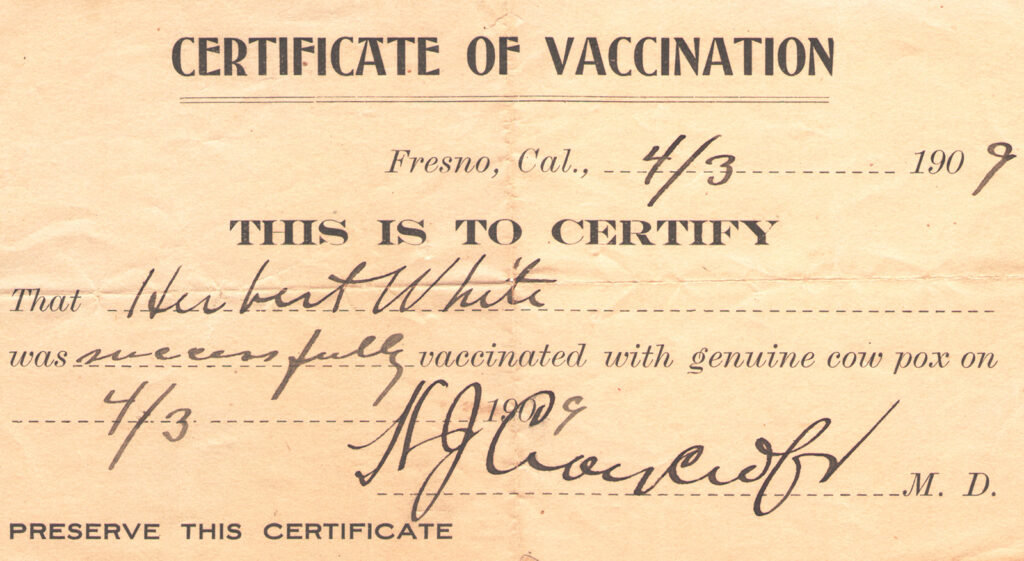

Many vaccination certificates were simpler and mostly of local use. On April 3, 1909, Dr. H. J. Craycroft certified that Herbert White was successfully vaccinated with “genuine cow pox,” thereby implying that White was protected from smallpox. He was advised to “preserve this certificate.” We don’t know White’s age, but he might well have needed the staid, 3-by-5-inch certificate to attend school in Fresno, California.

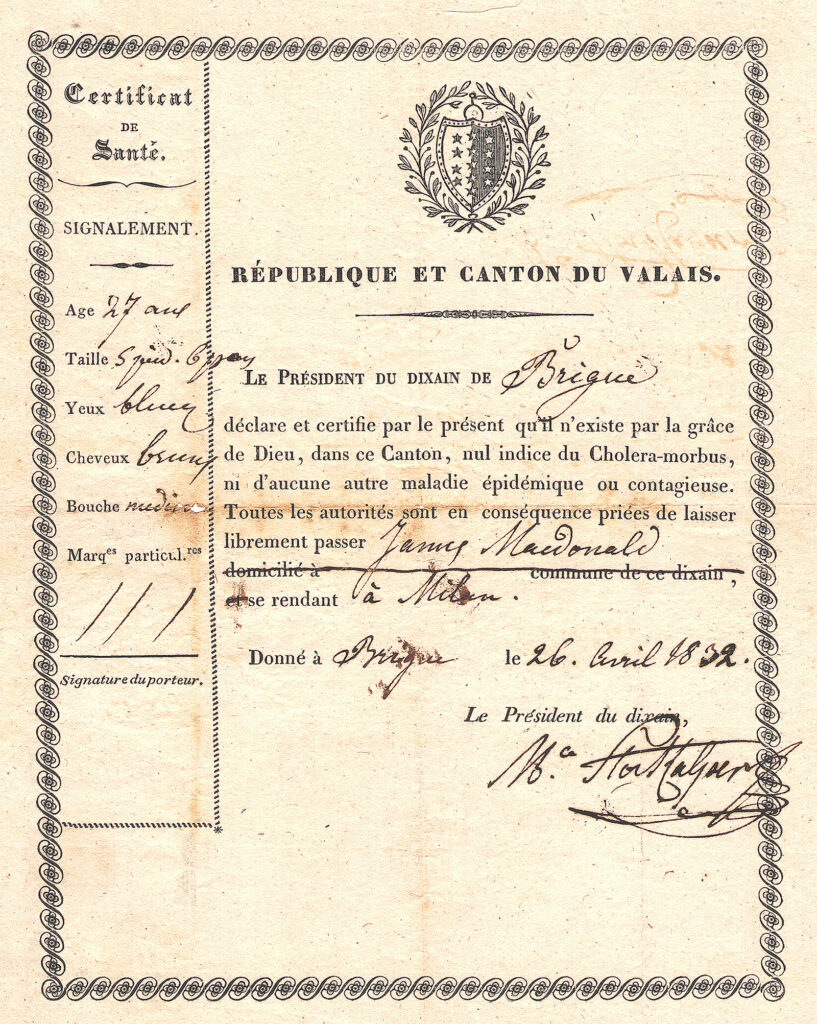

Some health passes are impressively elaborate in design, such as a certificate of health issued to 27-year-old James MacDonald in 1832, during the terrifying year in which cholera reached Europe for the first time. Verging on a pandemic, “cholera morbus” crossed the Atlantic and caused outbreaks in Canada and the United States later that year. As is still common, MacDonald is described by physical characteristics: age, height, eye color, hair color, mouth size, and any unusual marks. This certificate permitted the young man to leave a Swiss jurisdiction, the Canton of Valais, and proceed to Milan, Italy.

At the time, the canton was divided into 10 districts, called dixains (now spelled dizains). In the certificate the president of the Dixain of Brigue “declares and certifies by this present document that, by the grace of God, there is in the Canton no indications of cholera-morbus, nor any other epidemic or contagious disease. Consequently, all authorities are asked to let James MacDonald freely pass to Milan.” The simple document with personal details and a signature in ink had sufficient authority and authenticity to support its claim about MacDonald’s health status.

For a long time, printed health passes provided physical evidence for both the authenticity of the bearer and the authority of the issuer. Paper documentation remains, for now at least, our primary means of proving vaccination and negative test results. It is not yet clear how well virtual documents will work or whether new, universal infrastructure to support them can be established. For those pursuing digital health passports, the challenges are not just technical.

Will authorities be able to enact and enforce universal standards for who and what qualifies as a non-threat? Will all vaccines, which vary in effectiveness, be accepted equally everywhere? Can the organizations handling people’s health data be trusted? And can they prevent counterfeiting?

Whatever system arises, evidence for trustworthy authority and personal authenticity will remain as essential today during the COVID-19 pandemic as it was during earlier plagues.