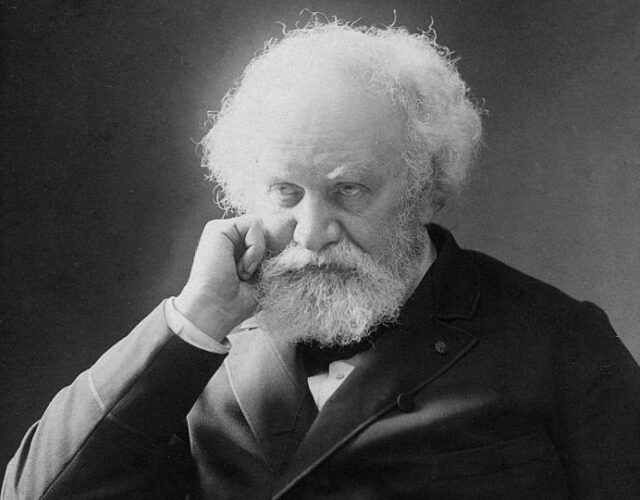

Of the 2.5 million people under siege in Paris during the War of 1870, the Prussian army offered just one of them free passage to leave the city—astronomer Jules Janssen. Janssen wanted to observe a solar eclipse in Algeria, and the Germans magnanimously put science above the fray of politics and told him he was free to leave.

Imagine the Germans’ shock, then, when Janssen spurned the offer. After months of suffering in solidarity with his fellow Parisians, he refused to accept the easy way out. Instead, with typical French flair, he informed the Germans that he would take to the air instead and soar over the siege in a hot-air balloon.

Through gritted teeth, the Germans wished Janssen luck. Then they warned him that they planned to shoot his balloon out of the sky—and shoot him as a spy when he landed.

This was a credible threat. The Germans had shot down other balloons and had executed other civilians as spies. But the astronomer never hesitated. He was determined to reach that eclipse.

Janssen’s determination had its roots in an eclipse two years earlier, which he’d observed in eastern India.

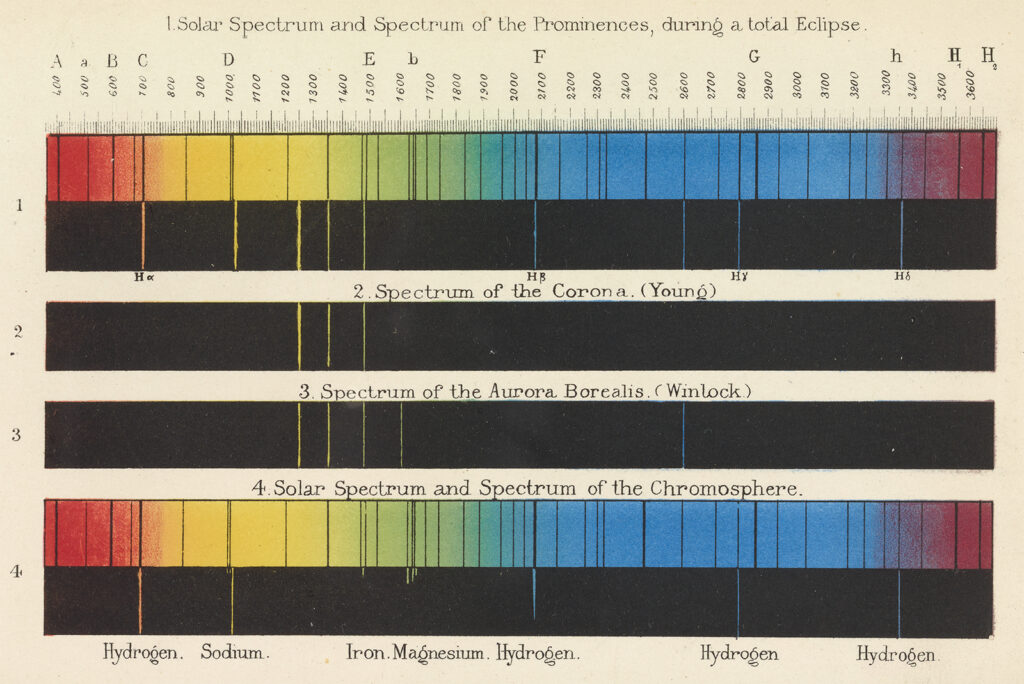

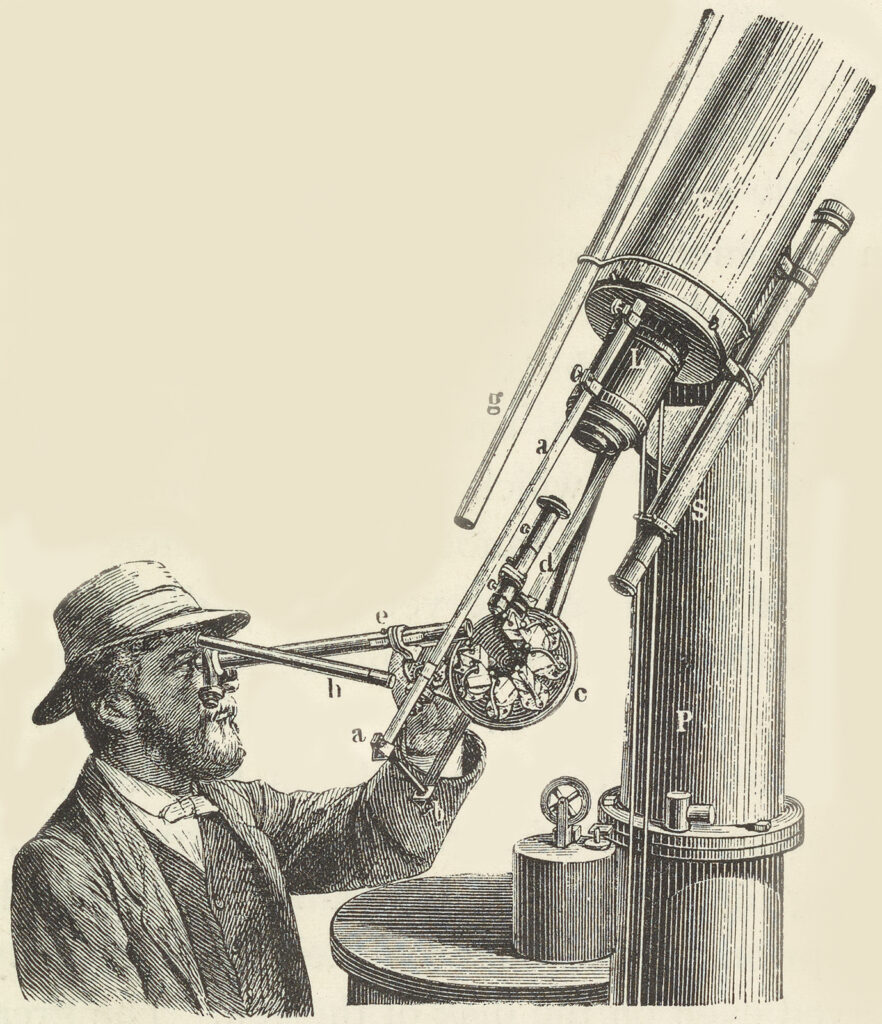

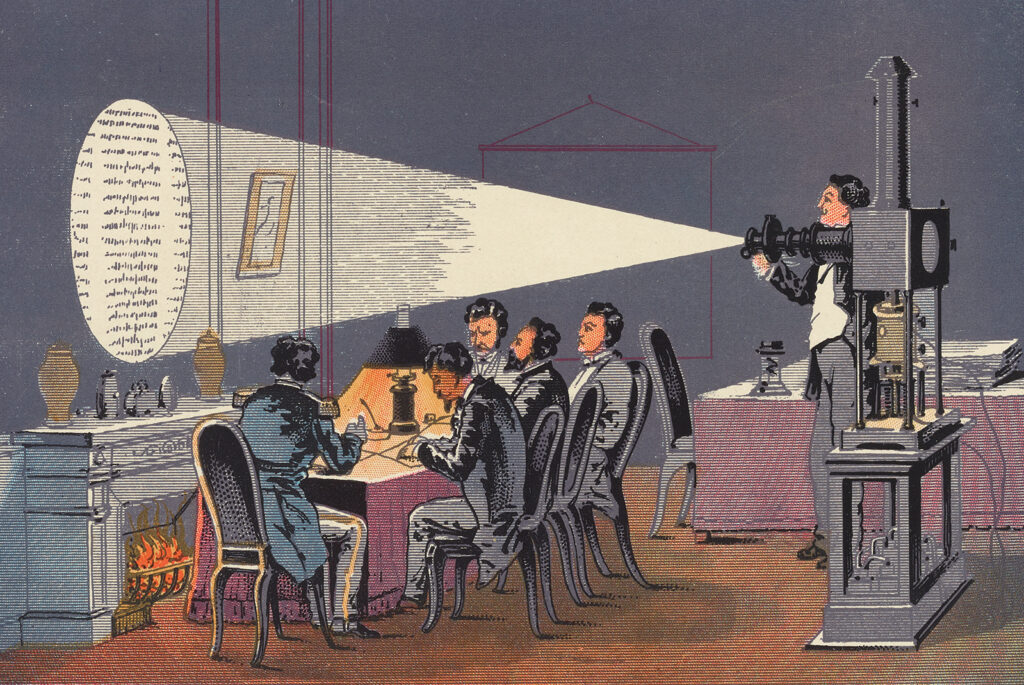

That morning, he had used a new-fangled instrument called a spectroscope, which separated light into individual colors and arranged them by their wavelengths. Each element on the periodic table produced a characteristic pattern of thin, colored lines, similar to a barcode. Hydrogen, for example, produced a sharp band of red light at 656 nanometers (nm), plus an aqua line and two purple ones at other wavelengths. By determining the barcode of each element in the lab and then examining the lines produced by sunlight, astronomers could determine what elements were present in the sun—an impressive achievement from 92 million miles away.

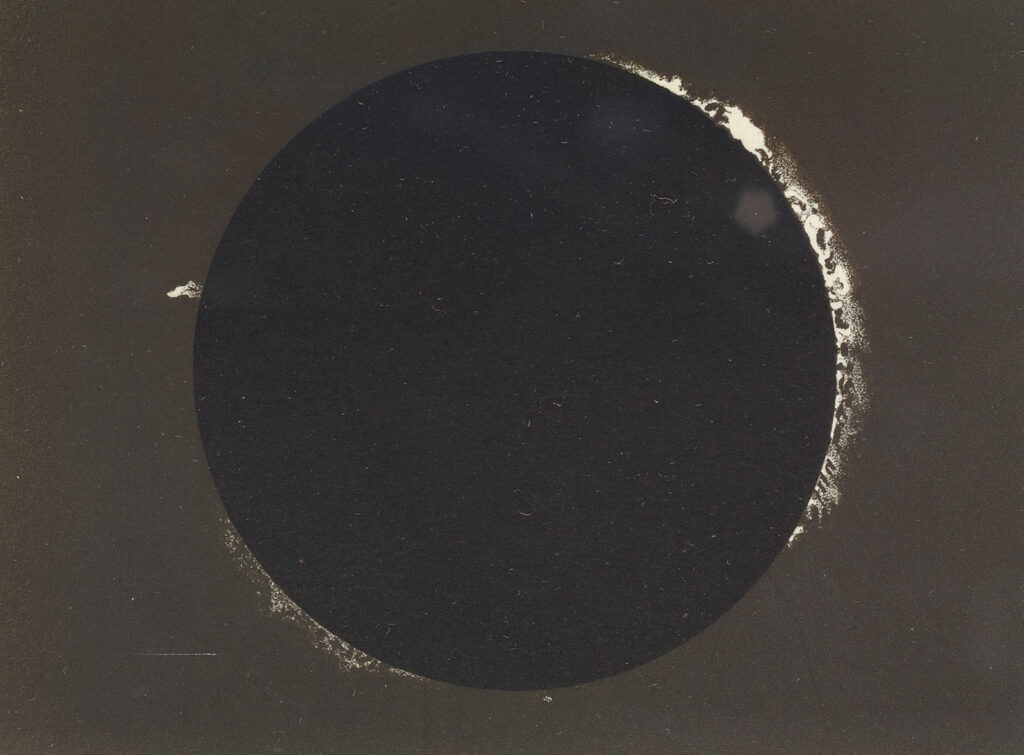

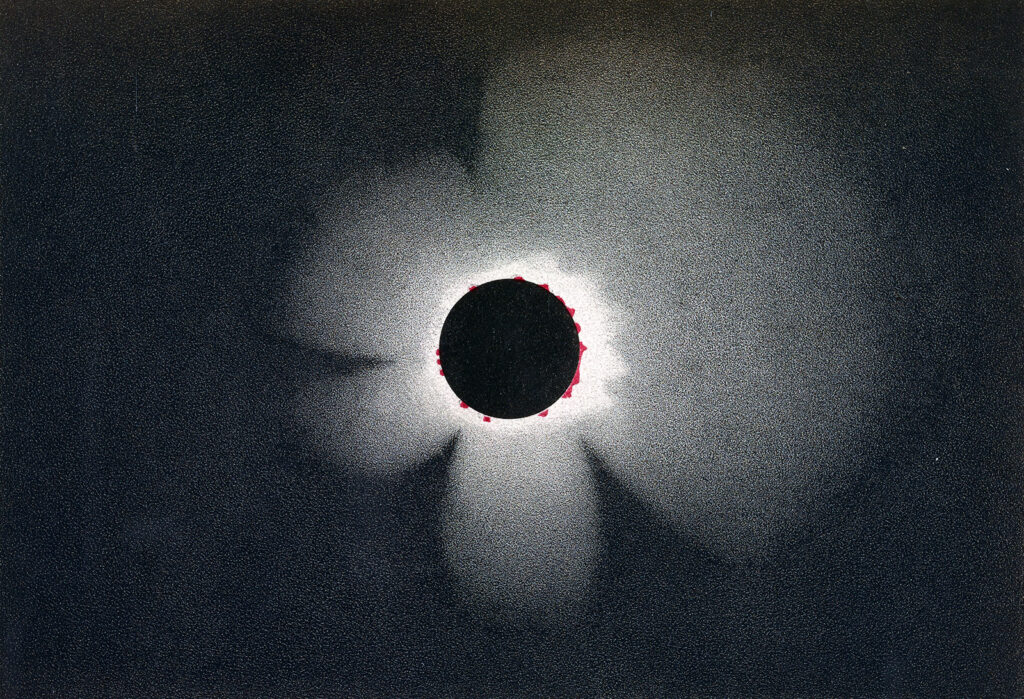

For the eclipse in India, Janssen used the spectroscope to observe the corona of the sun, its outer envelope. The glare of the sun normally overwhelms the corona, but the moon conveniently dims the sun’s body during an eclipse while leaving the corona visible. The eclipse gave Janssen seven precious minutes of darkness, and he hurried to analyze the bands of light. Right away, he saw the barcode for hydrogen—red, aqua, purple. There were other barcodes, too, including what looked like a double yellow line, indicating sodium.

But on closer inspection, Janssen noticed something odd. In the lab, the sodium doublet appeared around 589 nm. This line from the eclipse appeared a tad below 588 nm. It was just one nanometer—a billionth of a meter. But the difference bothered Janssen. Even after the eclipse passed, it kept picking at his mind. Had his instrument just been off-kilter?

Janssen had also been surprised at how blazingly bright the anomalous yellow line was. In fact, it was so bright that he wondered whether he could detect it even outside of an eclipse.

Unfortunately, clouds swept over India after the eclipse ended and covered the sun. So Janssen spent the day reconfiguring his equipment to block out all other wavelengths except for those right around 588 nm. The next morning, around 10:00 a.m., he tried again, focusing on the corona on the sun’s rim to avoid interference from the main body. Sure enough, he saw a blaze of yellow around 588 nm.

Janssen spent the next month refining his observations, then mailed a paper off to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. He didn’t know what he’d discovered, but he sensed it might be important.

Unfortunately for him, the intercontinental mail service wasn’t exactly a well-oiled machine. It took his letter two months to reach Paris. And during that time, another scientist nearly scooped him.

The English astronomer Norman Lockyer spotted that same yellow line independently in October 1868. This was months after the eclipse, but just like Janssen, Lockyer had discovered a way to isolate certain wavelengths of light and study the sun’s corona during daytime.

And unlike Janssen, Lockyer never shied away from leaping to big conclusions. (It was Lockyer, for instance, who first proposed that the pyramids in Egypt weren’t just tombs but astronomical instruments as well.) So as soon as Lockyer saw that bright yellow line, he declared he had discovered a new, extraterrestrial element. He named it helium—after Helios, a Greek god and the personification of the sun. Lockyer then staked his claim to helium by dashing off a paper to the leading scientific body in the world—the French Academy of Sciences.

Accounts differ on what happened next. But according to the most dramatic version, Lockyer’s and Janssen’s letters arrived on the exact same day at the academy. If so, it must have been a chaotic scene—which scientist deserved credit? As it was, the French Academy decided that the two astronomers would share credit for helium.

Still, other astronomers began to raise objections. They couldn’t deny the existence of the bright yellow line, but they rejected the idea that it arose from a whole new element. It was much more likely, they argued, that the line represented a common element behaving strangely in the sun’s extreme heat. Helium, they declared, was bogus.

This, then, was the backdrop for the December 22, 1870, eclipse in Algeria. Janssen needed to shore up his claim for helium, as it was still easier to observe that bold yellow line during an eclipse. Plus, who knew what new surprises he might see this time around?

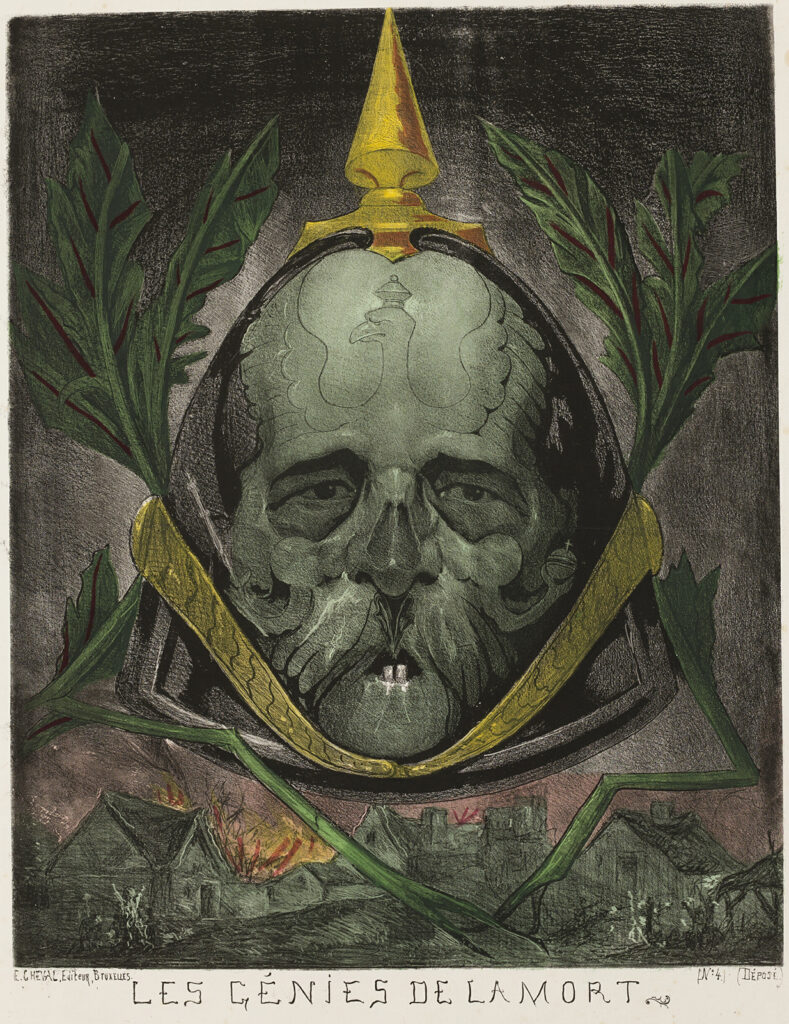

Unfortunately, he hadn’t reckoned on Otto von Bismarck.

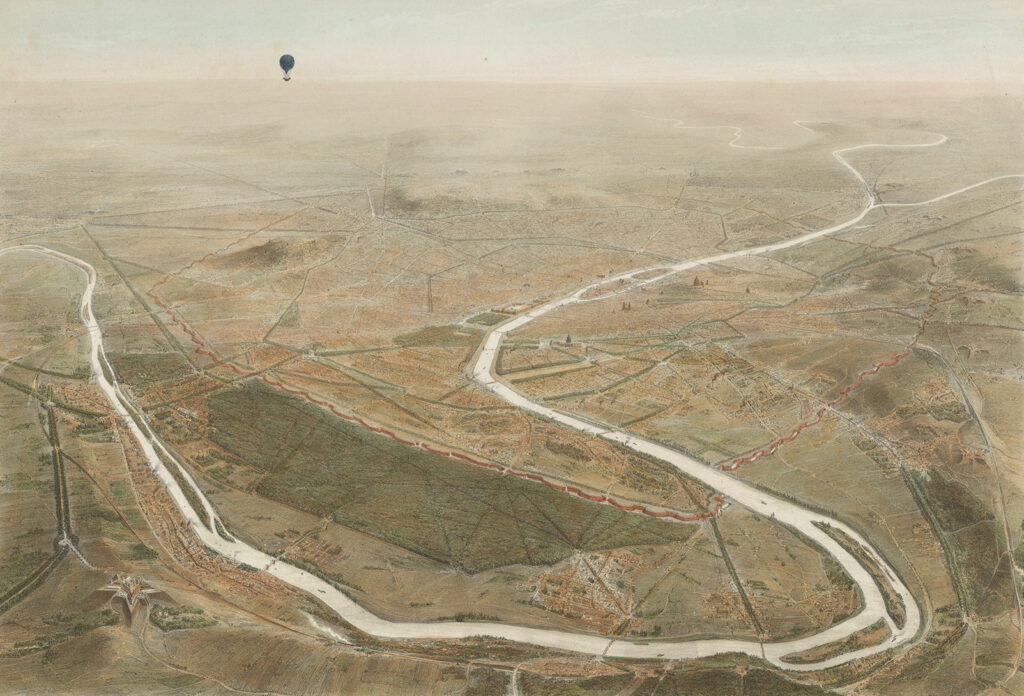

In the summer of 1870, the wily German chancellor goaded France into invading Germany and proceeded to rout the French army. Bismarck then marched on Paris, surrounding it in just five weeks. Some historians call it the original blitzkrieg.

Bismarck’s men quickly blocked every road and river into Paris, cutting off all supplies. Within weeks, people in Paris were chopping down trees on beloved boulevards for firewood. They took to eating pets, then animals in the zoo. Diaries talk of rat pâté. Bismarck even cut the telegraph line out of Paris, leaving the rest of the world ignorant of Paris’s suffering.

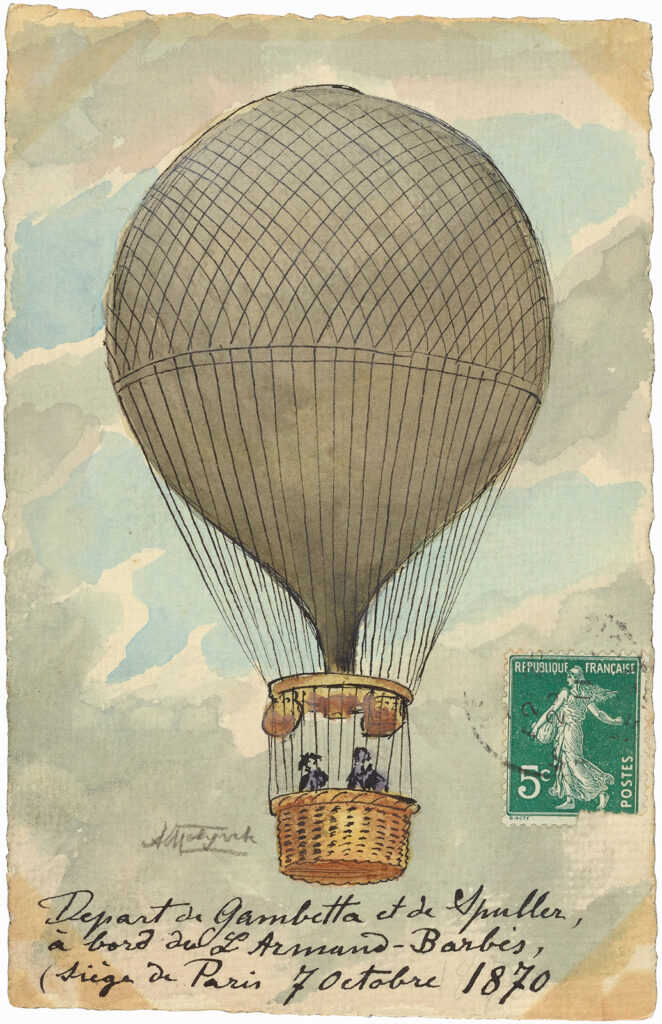

With no way to escape the city and no other way to rally support, the desperate French government began sending people up in hot-air balloons. Most carried a few passengers, some sacks of mail, and a cage of passenger pigeons for return messages. Parisians filled the canopies with gas intended for the City of Light’s famed streetlamps.

Ever stylish, the French gave the balloons dashing names—one was Liberty, another was Deliverance. They also honored several scientists, including Archimedes, Kepler, Newton, and Lavoisier. Unlike normal balloon flights, these commando runs leapt as high as possible as quickly as possible to escape the dreaded German artillery.

German soldiers took potshots anyway and sometimes scored hits. Léon Gambetta, the minister of the interior and a future prime minister, suffered a wound to his hand while fleeing. Even after clearing the siege lines, the balloons were not out of danger. Often, Prussian cavalry would pursue them. The Germans then executed some French aeronauts as spies. No quarter, no mercy, was given.

Despite these risks, as the eclipse approached, Janssen began making arrangements for a balloon flight of his own. He simply had to reach Algeria. That’s when the Germans sent word that he didn’t have to risk his life after all. In the spirit of fair play, Lockyer had brokered an agreement of safe passage for Janssen to leave the city. And incredibly, the German chancellor agreed.

It’s not clear why Bismarck did so. Was he a secret astronomy buff? More likely, he saw a chance to score some cheap, easy points with the international community. Sure, let the astronomer go. Why not?

Regardless, Janssen snubbed the offer. He was a patriot, and he vowed to take his chances in the air. Bismarck in turn vowed to bring the astronomer down to earth—promising that any stars Janssen saw on his balloon flight would be his last.

Janssen and his copilot climbed into the basket of their balloon, La Volta, early on the morning of December 2. Janssen checked over his astronomical equipment one last time, and around 6:00 a.m. ordered the men holding the ropes to let go.

As the balloon shot upward in the dark, Janssen could see the white light of dawn to one side, translucent and pure. Beneath him, silent orange fires burned, tiny volcanoes erupting across Paris.

A few minutes later the silence was broken by the rifles of Prussian soldiers, who created their own tiny bursts of orange below. Thankfully, the gusting dawn winds pushed Janssen and his copilot beyond their pursuers, and the two men relaxed.

But as they drifted farther, they realized the winds weren’t letting up. Indeed, they were buffeting the basket and pushing the balloon faster than expected. Eventually the duo could see the Atlantic Ocean looming. They began a desperate attempt to drop altitude before being swept out to sea.

Finally, after five hours and 225 miles, they crashed down in a field just short of the ocean. They were immediately surrounded by farmers, who were hungry for news about Paris. The farmers then served the famished aeronauts their first hearty meal in months, a lunch of roast chicken, butter, and eggs.

Janssen rested for a few days, then boarded a train for Tours, where the exiled French government had gathered. There, he relayed a secret message to the escaped Minister Gambetta. Janssen had been acting as a spy after all. He then raced off to Algeria.

Alas, the whole grand adventure ended in a fizzle. After months of siege and a daring escape, Janssen arrived in Algeria to find the skies overcast. As one historian said, he was “shut behind a cloud-curtain [even] more impervious than the Prussian lines.” There would be no eclipse, no observations, no yellow lines. Janssen’s only consolation was that Norman Lockyer, observing the eclipse in Sicily, suffered the same cloudy fate.

Today we know that blazing yellow line in sunlight does in fact represent helium, the second most common element in the sun. Janssen and Lockyer now share credit for its discovery, and it remains the only element first observed on another celestial body. How fitting, then, that the man who first spied it had once taken to the skies himself in pursuit of scientific glory.