There’s a Class(ification) for That!

My trip to Rare Book School, or, how I spent (part of) my summer.

My trip to Rare Book School, or, how I spent (part of) my summer.

In early June, I traveled from Philadelphia down to the University of Virginia in Charlottesville for Rare Book School. The goal was to learn rare book cataloging from the GOAT (greatest of all time), Deborah J. Leslie. Who is Deborah J. Leslie? What’s Rare Book School? What’s a rare book? And what’s rare book cataloging? Let’s start at the beginning.

Deborah J. Leslie is an authority when it comes to rare book cataloging. She has more than 30 years of experience as a rare book and special collections cataloger, chaired the Bibliographic Standards Committee, was the chief editor of Descriptive Cataloging of Rare Materials (Books)—or DCRM(B), the rules that rare book catalogers follow—for the American Library Association’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Section, and has taught the rare book cataloging course at Rare Book School since 1998. She is a leader in the field, and I felt incredibly lucky to attend her course.

Rare Book School is summer camp for book nerds. It’s our little place. We learn about the history of books, how books are made, and about bibliography, papermaking, and more. All these topics are covered in separate, specialized classes so that you can dive deeply into one rabbit hole of book history (even though each rabbit hole takes you down another . . . and another . . . ).

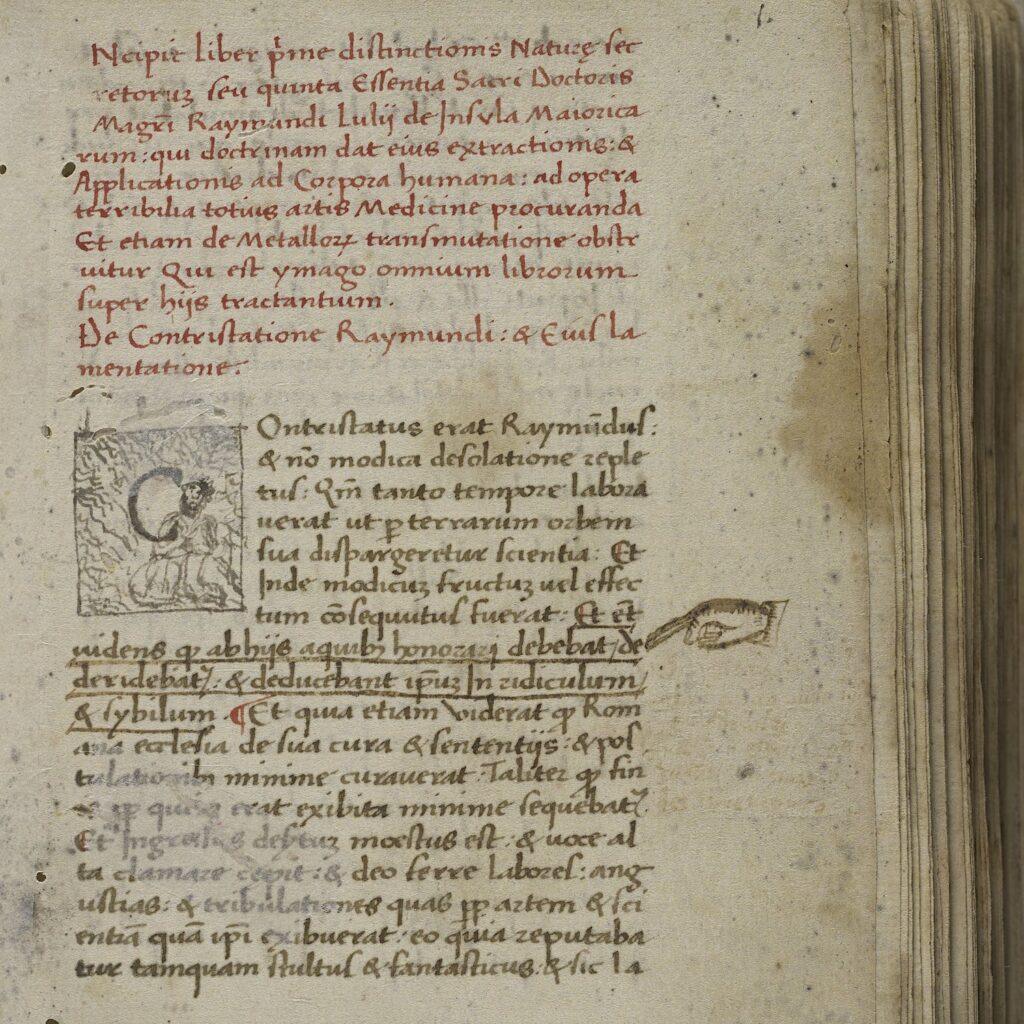

A rare book is a work produced during the “hand press era” (1450 through the early 19th century), or one that has enhanced value due to its importance, scarcity, or association with a historically significant author, publisher, or owner. During the hand press era, which began with Gutenberg’s invention of the moveable-type printing press, paper was handmade and books were typeset and bound by hand. Cataloging is the process of creating the records found in a library’s catalog. These records contain information about the physical book and about the subject matter inside.

Now that we’ve laid the groundwork, we can move on to why I enrolled in a class about rare book cataloging. The Science History Institute’s Othmer Library holds more than 150,000 modern books and journals, and more than 7,000 volumes of rare materials. That’s a lot of books to catalog! I am one of two cataloging librarians here at the Institute, though up until now, my colleague was the only rare book cataloger. In my position, I create bibliographic records for modern books, oral histories, archival records, and journals. Some of my responsibilities include “copy cataloging,” which is ensuring the book or item in hand matches an existing record in WorldCat, the world’s largest public access catalog, enhancing the record if needed, and adding it to our online catalog.

Rare book cataloging is its own beast with its own set of intense rules that take into account the unique aspects of rare books, such as archaic spellings and letterforms, printing errors and variations that arise due to the manual nature of book production, and information about how the book was laid out and assembled.

Over the weeklong rare book cataloging course, we learned to catalog books using DCRM(B). This is more than 200 pages of rules guiding catalogers through different aspects of the book. At Rare Book School, we were up from dawn to dusk pouring over DCRM(B) and rare materials. OK, just kidding. It wasn’t that intense, but we were in class from 8:30am until 5pm, plus lectures and late hours that went until 7:30pm, so it certainly felt like dawn to dusk.

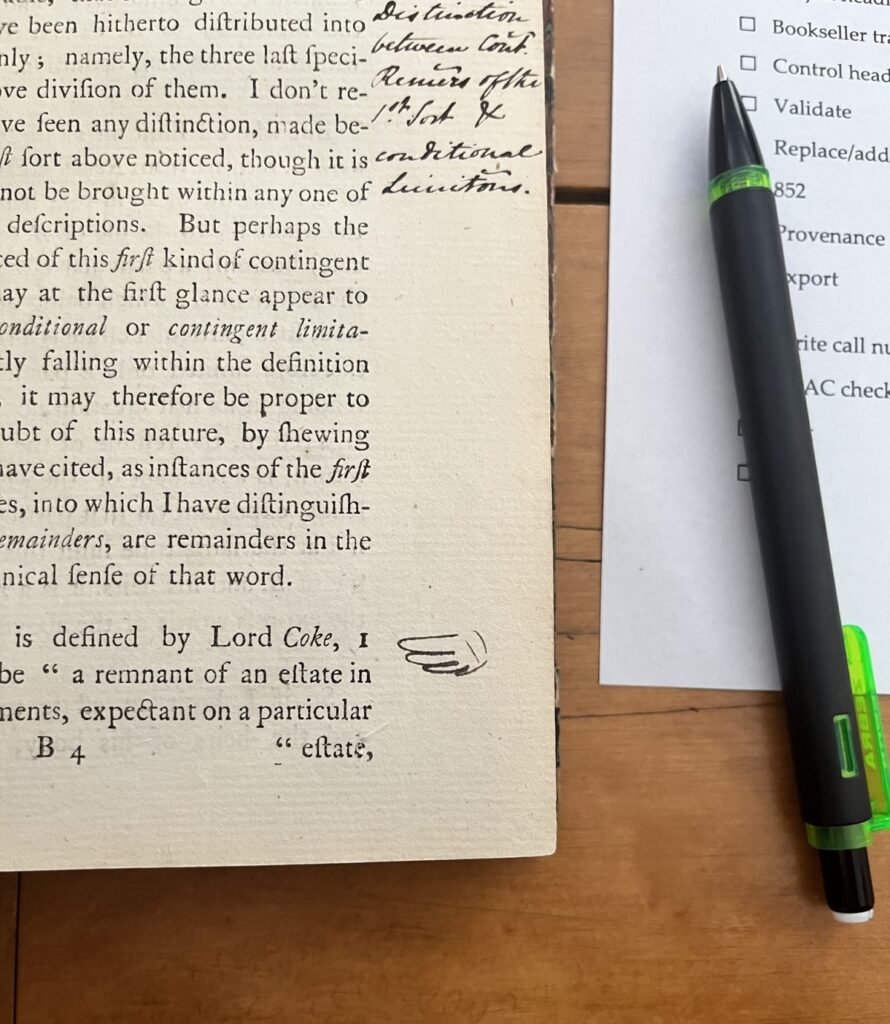

At the start of the week, we were each given two books to catalog for the remainder of the week. I was given An Essay on the Learning of Contingent Remainders and Executory Devises (1776) by Charles Fearne and Mormon Wives, a Narrative of Fact Stranger Than Fiction (1856) by Metta Victoria Fuller.

As we learned about best practices, rules for certain situations, and caveats, we applied that knowledge to the rare books we had been given. We learned to accurately transcribe the titles, watching out for the pesky V/U issue (until the early 17th century, the standard Latin alphabet didn’t distinguish between these letters, or “I” and “J”!). We had to accurately devise and write out the collational formula, which is a kind of shorthand that tells you how many times a sheet was folded to make the pages of the book, and how those folded sheets were ordered and assembled to make the final book. We learned how to describe the binding of the book, to note previous ownership if names were written on the inside front cover, and how to decipher whether our copy was a different edition, impression, or issue than another copy. And that was just getting started!

Creating a strong and effective bibliographic record requires significant attention to detail and accuracy in describing the material so that researchers viewing your record have the information they need: Is this the edition they are looking for? Was this copy previously owned by someone they are researching? Are all of the pages numbered correctly—an important detail for the researcher looking for copies with incorrect pagination!

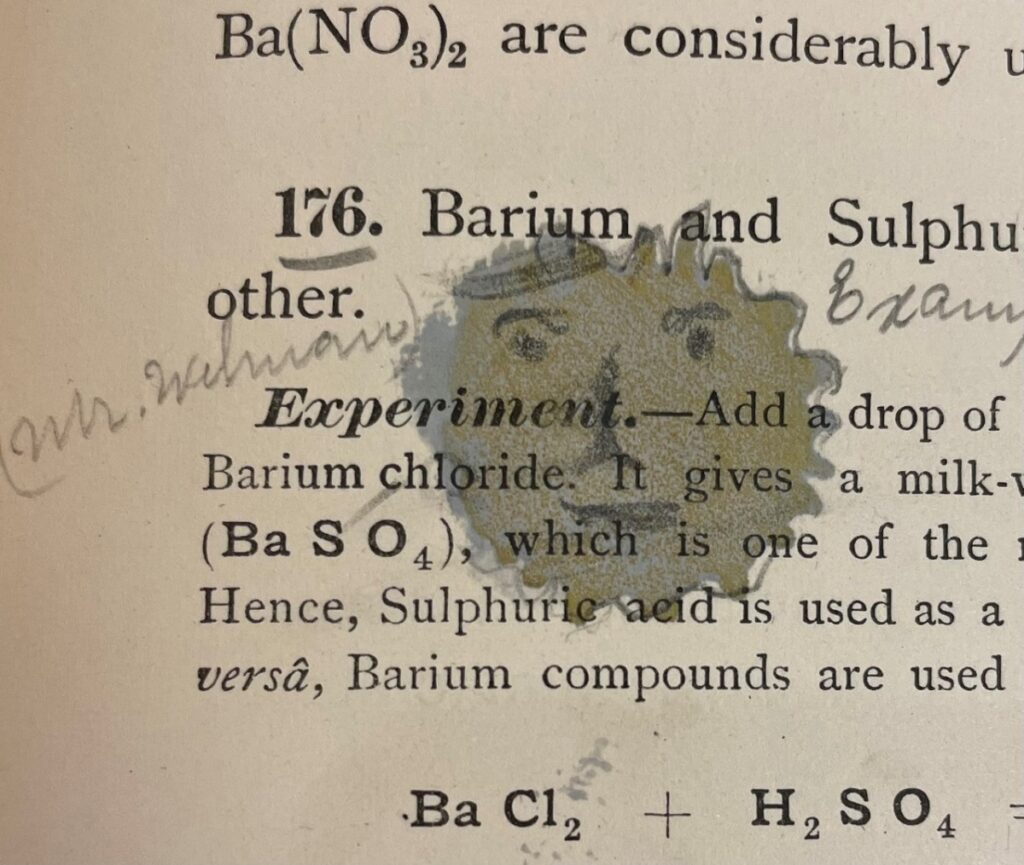

We were encouraged to get descriptive. Are there manicules or marginalia throughout the book? Include it in the record. Is there a name written on the inside front cover? Add that to the record. Is the book’s binding original or contemporary? Include that! Did someone conduct a chemistry experiment a little too close to the book causing a splatter of something to fall on the pages and then they decided to play it off by drawing a face on it? Say so!

Attending the Rare Book Cataloging class at Rare Book School this summer has really helped me in my cataloging endeavors, specifically for rare materials but for modern ones as well. Both categories require negotiation between standards, rules, and quality descriptions.

Featured image at top: Detail of the title page from Musaeum metallicum in libros IIII distributum by Ulyssis Aldrouandi, patricii Bononiensis, 1637. Science History Institute

Pets aren’t allowed in our museum or library, but you’ll find plenty of them in our collections.

Why oral history is critical for the history of science and engineering.

A chemistry curriculum with bonds beyond the molecule.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.