In the 19th century a mysterious illness swept rural New England. Often called the Great White Plague for how pale it made its victims, it was also called “consumption” because of the way it literally consumed people from the inside out, gradually making them weaker, paler, and more lifeless. Today we know consumption as tuberculosis, an infectious bacterial disease that attacks the lungs and causes a hacking cough, a wasting fever, and night sweats. But back then, many people were convinced it was caused by vampires.

Credits

Hosts: Alexis Pedrick and Elisabeth Berry Drago

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

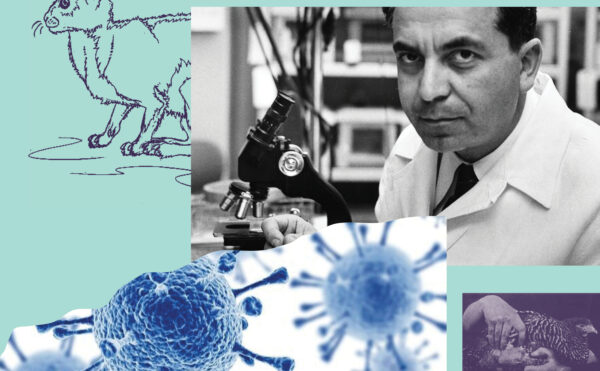

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Resource List

Consumptive Chic: A History of Beauty, Fashion, and Disease, by Carolyn A. Day

Fevered Lives: Tuberculosis in American Culture since 1870, by Katherine Ott

Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires, by Michael Bell

The Great New England Vampire Panic, by Abigail Tucker

Transcript

Alexis Pedrick: Micheal Bell didn’t start out as a vampire hunter.

Michael Bell: Well [laughs] yeah. It was sort of an accident.

Alexis Pedrick: In 1981, he was a newly minted folklorist doing a survey of Southern Rhode Island when things took an interesting turn.

Michael Bell: One of the interns working with me said, “You know, you got to go interview this guy who is in Exeter. He’s kind of the unofficial town historian. He knows everything and everybody.” And she said, “When we go there, you’ve got to be sure to ask him about the vampires in his family.” So, I went, “Ho! What? Wait. [laughs] Vampires in, in Rhode Island?”

Alexis Pedrick: Exeter, Rhode Island, 1883. In the late 19th century, the southern part of Rhode Island was sparsely populated. The Civil War had ravaged the area and the lucky young men who’d survived the war had mostly left town for better opportunities. Deserted Exeter, as it was known, was home to subsistence farming families who scraped out their livings from the rocky, barely fertile soil. One of them was the ill-fated Brown family.

Lisa Berry Drago: George T. Brown and Mary Eliza Brown had three children, Mary Alice, Edwin, and Mercy Lena. In December of 1883, Mary Eliza Brown died of a mysterious illness. Just seven months later, one of her daughters, Mary Olive Brown died, too, from the same thing. Within a few years, the son, Edwin Brown also became ill.

Alexis Pedrick: By this point, it was clear that something was plaguing the family and, sure enough, Mercy Lena Brown eventually became ill as well and died in 1892. With just one remaining family member, his son, Edwin and no solutions, George T. Brown was desperate. Friends and neighbors pleaded with him to consider the obvious. There must be a vampire haunting his family and, if he didn’t act quickly, it would get Edwin next.

Lisa Berry Drago: George Brown was alarmed. He took Edwin to the doctor but he knew it wouldn’t do any good. He knew the only diagnosis he’d get would be a death sentence, just like his wife and his daughters. He was desperate. So, when his friends and neighbors urged him to try the quote, unquote, “Old time remedy,” he agreed.

Alexis Pedrick: That remedy involved digging up each of the dead family members from their graves. They started with Mary Eliza and Mary Olive, who have been dead for years by this point. All that was left of their bodies were skeletons with a little bit of hair on the skulls.

Lisa Berry Drago: But Mercy Lena had only died a couple of months earlier in January. She hadn’t even been buried in the ground yet, because it was still frozen solid. So, they took her body from the above ground crypt where she was being stored and they examined her vital organs.

Alexis Pedrick: They were looking for signs that death was quote, “Not complete,” and they found them. Mercy Brown didn’t look anything like her mother and sister. Her body was still fresh. Her organs were intact. Her heart had liquid blood in it. Mercy Lena Brown was clearly a vampire, an undead being subsisting on the living tissue and blood of Edwin.

Lisa Berry Drago: The old-time remedy instructed that they should cut out her heart and liver, burn them on a rock, mix the ashes with water, and give it to Edwin to drink. Their hope was twofold. One, that Mercy Lena would now become fully dead and, two, that drinking this medical magical potion could cure Edwin. Unfortunately, it didn’t and Edwin died just a couple of months later, leaving George Brown all alone.

Alexis Pedrick: At this point, you might be wondering if you’ve clicked on the right podcast. Why is Distillations telling you a vampire story? And, full disclosure, we love vampires. We’ve been secretly scheming about a way to get them into an episode for years and we finally managed to do it without abandoning what Distillations is all about. You see, this story is actually about a mysterious contagious disease, one that was often lethal and one that science had no answers for.

Lisa Berry Drago: Stop us if this sounds a little too familiar.

Alexis Pedrick: We know. We know. We promised we were getting away from COVID and I’m sorry. We’ve lied, kind of. This story is not explicitly about the Coronavirus but there are some big parallels. The Brown family, like so many others in the 19th century, had succumbed to a mysterious fatal disease. We now know it as tuberculosis, but at the time, it was called consumption for the way it literally consumed people from the inside out, gradually making them weaker, paler, and more lifeless until they were gone. It attacked the lungs, produced a hacking cough, a wasting fever, even night sweats.

Lisa Berry Drago: Today, we know that tuberculosis is an infectious bacterial disease that attacks the lungs. We now understand that the infectious organism that causes it is Mycobacterium tuberculosis humanis and we have antibiotics to treat it. We also have a vaccine for it, but back in Mercy Brown’s time, we had none of this. Medical science was still trying to make sense of it, even though it had been around for thousands of years, which is humbling, if you ask me when you consider that it took scientists all of one year to figure out and develop a vaccine for the novel Coronavirus.

Alexis Pedrick: Still years away from understanding the cause of tuberculosis and decades away from a vaccine, medicine at the time offered many theories of little use and, in the absence of solid medical guidance, the hardest hit, most desperate communities, many of which were isolated and rural came up with their own solutions like that old time remedy.

Today, they might seem ridiculous, more supernatural than medical, but however bizarre they might seem to us now, at the time, they made a lot of sense for people like George Brown who saw it as their last hope. I’m Alexis Pedrick.

Lisa Berry Drago: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago and this is Distillations. Chapter one, a germ with fangs. Tuberculosis or consumption, as people in Mercy Brown’s time called it, has been around since at least 5000 BCE, but in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century, it was the leading cause of death in America, in the Northeast, especially.

St- statistics are hard to come by, but some people think it caused as many in … Statistics are hard to come by, but some people think it caused as many as one in every four deaths in this period.

Alexis Pedrick: Tuberculosis is a confusing disease. It can look very different from person to person. Some people have latent versions for years before ever getting sick. Some people have the so-called galloping variety, where it hit them hard and fast and then they died. This is the kind many people think Mercy Brown had, since she got sick after Edwin but died before him and some people never got any symptoms at all, but judging from all the sick people around them, they were probably just asymptomatic.

Lisa Berry Drago: Mmm! Yeah.

Alexis Pedrick: In fact, some people think Edgar Allen Poe might have been one of these people. Everyone around Poe got tuberculosis from his brother to his mother to his lady friends. If you were a woman and Poe loved you, well, you were screwed because they all got tuberculosis and died. But, Poe never seemed to get it.

Lisa Berry Drago: Looking back, it seems like Poe might have been an asymptomatic carrier and it’s possible George Brown was, too. But for every Poe and George Brown, there seemed to be far more people with active consumption. Like the Browns, entire families could be wiped out and it was a miserable way to go. As the disease progressed, their lungs wouldn’t be able to support the oxygen supply. Their muscles would atrophy. Eventually, they’d start coughing up blood.

Michael Bell: You know, starting with, like, spoonfuls and towards the end, be cupfuls of blood. So, those taking care of the sick person would come into the room in the morning and see that, “Oh, my gosh, Mercy has blood at the corners of her mouth and her bedclothes were stained with blood. Where did this bright red blood come from?”

Alexis Pedrick: That’s Michael Bell, the folklorist turned vampire hunter we heard from at the beginning of this episode.

Michael Bell: Something is sucking the life, actually sucking the blood out of her. And what seemed more unnatural is that it seemed to happen with young people more often. The physicians were totally unable and unaware when it came to pulmonary tuberculosis or consumption. They didn’t know what caused it. It was like, “Oh, too much dancing,” or you lived closed to, you know, too, just too much water in the soil.

Alexis Pedrick: These were some of the other suggested causes of consumption, excessive intellectual work, disturbed electrical energy, eating ethnic foods, overindulging in alcohol, and masturbation. In her book, Fevered Lives, historian Katherine Ott says that medical practice in the late 19th century was a virtual free-for-all. She writes, quote, “The average physician practiced a rich mixture of common sense, folklore, popular knowledge, and medical doctrine.”

Lisa Berry Drago: By today’s standards, almost any 19th century doctor would be considered a quack. In George Brown’s time, medicine was a smorgasbord, a combination of empirical reasoning, local customs, magic, and wishful thinking.

Michael Bell: And throughout most of that period, the medical profession was still practicing, uh, the Galen medical tradition, which goes back to ancient Greece, of the four humors of the body and you have to keep those in balance, so if they’re not in balance, you know, you bleed people, you make them throw up, you give them [immedics 00:10:27]. [laughs] So, a- at a time when the medical profession is, is cutting people and bleeding them to cure them, the so-called vampire tradition, doesn’t seem so crazy.

Lisa Berry Drago: Without much else to go on, the available evidence surrounding consumption did seem to point towards vampires.

Michael Bell: If you take a little chart and tally up the symptoms of consumption and then the attributes of a vampire, I mean, they match up very well.

Lisa Berry Drago: Think about it. The blood around the mouth, the weakness, the pallor.

Alexis Pedrick: In Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Lucy grows weaker and paler each day as Count Dracula drinks her blood each night. Eventually, she dies and, of course, becomes a vampire herself, but those descriptions of her wasting away, becoming pale and gaunt, Stoker might as well be describing tuberculosis. Michael Bell told us one historical account of a young girl sick with consumption in the 1800s who recounts her dead sister coming into her room and sitting on her chest each night, pinning her down.

Michael Bell: As your lungs dissolve, your chest starts to sink and it feels like there’s increasing pressure on your chest. So, yeah, the, the idea that something’s coming at night and sitting on your chest and putting pressure on you and forcing, you know, the blood out of you. That’s a vampire. This vampire was really, you know, a bacter-, a germ with fangs. You know, the vampire was really in a microscopic animal that was killing people.

Lisa Berry Drago: But, of course, no one knew that yet. And as tuberculosis spread throughout New England, so did the fear that vampires were the culprit. Chapter two, the vampire hunter.

Alexis Pedrick: Michael Bell talked to us from his home in Texas right after those crazy snowstorms they have last winter. He had just gotten his water back when we spoke to him.

Michael Bell: I mean, we went from minus one and then a week later, it was 81. The ground has thawed. We can exhume bodies now. [laughs]

Alexis Pedrick: Since Michael is the first folklorist we’ve ever interviewed, we asked him to give us a quick explanation of what exactly that is. He started by reading us this definition from the American Folklore Society.

Michael Bell: “Every group with its own sense of identity shares folk traditions and that is the things that people traditionally believe, like planting practices, family traditions, uh, vampire practices, the things that people do like dance, make music, the things people know, how to build an irrigation dam, how to nurse an ailment, hmm, and the things that people say. Personal experience stories, riddles, songs, legends. Folklore exists alongside of official culture but outside and not sanctioned by official culture.” So, we have folk history, oral history, people’s memories, and then we have, you know, official history.

Lisa Berry Drago: Michael collects folk history by talking to people about their memories and their family legends. That’s why he went to talk to that unofficial town historian about the vampires in his family in Southern Rhode Island. His name was Everett Peck and he was a relative of Mercy Brown’s.

Michael Bell: We went and met Everett Peck down at the end of Sodom Trail, of all places, and he started telling me about Mercy Brown, who was a, a vampire. Before I could even turn on the, at that time, it was a cassette recorder. So, in the, the beginning of the interview, Mercy’s name is gone. It just says, “Brown was a relative. I can’t tell you how we are related, but we are related.” [laughs] And so, I sat there en- enthralled, really, for quite a long time while he related, uh, the story of Mercy Brown.

Everett Peck: Brown was a relative. I can’t tell you right now how we’re related, but we are related. My grandmother was a Brown. And it was told to me as a kid, you know, from my mother.

Michael Bell: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Everett Peck: And when we went to the cemetery, there was Mercy Brown. Right side was sort of, you know, and just one lot or two over from where my parents and all buried and there now. And, they say, “Well, don’t go running over there because don’t touch the stone because this awful thing that took place years ago.” Now, they … What they do here, they changed around as if I believe in vampire. Now-

Michael Bell: That makes-

Everett Peck: … that ain’t what I’m saying. I’m just revealing with they believed.

Michael Bell: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Everett Peck: And how they had to handle their own problems, see? So, they had to come down with some disease, young and old.

Michael Bell: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Everett Peck: All of a sudden, and a- anything that they did didn’t seem to stop it.

Alexis Pedrick: That interview with Everett Peck changed the trajectory of Michael Bell’s career. Now, 40 years later, his documented 80, eight zero, vampire exhumations in the Northeastern United States, mostly in New England and he wrote a book about them called Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires.

Lisa Berry Drago: Mercy Brown’s exhumation wasn’t an isolated event or even one a few. It was but one instance of a very popular practice, what Michael Bell calls the New England vampire tradition.

Michael Bell: You know, at the time, I really believed it was just the tip of a larger iceberg because of the chances of someone telling the story and then the story getting, you know, recorded in, in a, in a place that would, would be accessible to someone doing research like me. You know, uh, not high.

Alexis Pedrick: Over the years, Michael has documented these exhumations by piecing together things like oral histories, newspaper accounts, and death records until they paint a picture of what happened. What he rarely gets, though, is any physical evidence because he can’t go around digging up graves. That’s illegal now, but he did get his hands on an actual vampire grave in 1991, 10 years after he learned the story of Mercy Brown. He got a phone call from Connecticut state archeologist about a curious incident in the town of Griswold. Some boys have been playing in a large gravel pit, you know, as you do.

Michael Bell: And, uh, a skull popped out [laughs] next to one of them, start and rolled down the hill with them, which kind of freaked them out. And [laughs] and as Nick said, he did the right thing. You know, he didn’t take it home and put a candle on it and go, “Cool!” [laughs] You know, he told his parents.

And, uh, at first, you know, the authorities thought, well, maybe we’ve, we got another serial killer, because they had one in that area of Connecticut, but then they looked at it clo- more closely, said, “No. This is, this is a job for the archeologist, because this is really old. This, these bones are really old.”

Alexis Pedrick: The archeologist, Nick Bellantoni, realized that this mining pit was on top of an old, unmarked cemetery. He was tasked with moving its 29 graves and in the process, he discovered something really odd in one of them. It was marked J.B. 55, most likely for a 55-year-old man with the initials J.B.

Michael Bell: He found that this person’s skull had been removed from it’s normal position and placed basically on top of the chest and that the two femurs were placed in a kind of cross pattern over his chest with a skull on top. They found that some of the ribs have been rearranged and broken actually, but they showed lesions, which would indicate a chronic pulmonary disease, probably tuberculosis. In any event, would have been probably interpreted as, as consumption. And so, we put our heads together and basically figured this was an exam- you know, an actual physical example of exhuming a body to try to stop consumption from killing other people.

Alexis Pedrick: J.B. 55 was just the latest evidence that this whole vampire business was truly a thing. It crossed state borders and eventually made its way even to Canada. It pointed to a full-on vampire panic. But how did the idea of vampires ever even make its way to rural isolated New England in the first place?

Lisa Berry Drago: Chapter three, Rhode Island, the Transylvania of America. Edward G. Petit is a vampire expert. He also creates public programs down the street from us at Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum & Library. We talked to him about the mysterious origins of the word vampire.

Edward G. Petit: The etymology of it is, is uncertain. We’re not quite sure where it comes from. There’s a Slavic opiri word. There’s these other vampir, vapir, uper, ubyr words, but we’re not quite sure exactly when they come into language and I like that that, that in itself is like a metaphor for what a vampire is. It’s so far back that you don’t know where it actually comes from.

Alexis Pedrick: But we do know this. Most cultures around the world have some kind of vampire myth in their past and they’re all variations of the same theme. An undead person subsisting on the vital essence of a living person. The most famous brand of vampire is the one that hails from Eastern and Northern Europe. Count Dracula’s home is, of course, Transylvania, a region in Romania, but vampire folklore was basically absent in England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, i.e. the places where New England’s early settlers mostly came from.

Michael Bell: It’s, it’s a puzzling question. How could this have come to New England by at least 1784, which is the earliest case I found. To me, the answer is it, it arrived here with immigrants from Eastern Europe, perhaps during the, the Revolutionary War when there were, uh, mercenaries hired by the British troops, the Hessians, and Hessians weren’t just Germans. Now, we think of Hessians as Germans. They actually were recruited from, from all over Europe and, and including many places of Eastern and Northern Europe. So, they could have brought this practice with them.

Lisa Berry Drago: And of all the 80 exhumations Michael Bell has uncovered in and around New England, the majority took place in Rhode Island.

Michael Bell: Rhode Island still is the Transylvania of America, I guess, and, and Exeter would be the Transylvania of Rhode Island.

Alexis Pedrick: Why Rhode Island? Michael Bell says it goes back to the fact that it was settled by Roger Williams, who left Massachusetts because of religious persecution. As a result, Rhode Islanders were more open to alternative ideas.

Michael Bell: More apt to be looking at almanacs to decide, you know, how to, how to run their lives and look into astrology. And, uh, if I think it’s, uh, telling that no witches were ever executed in Rhode Island. They were in Connecticut. They were in, in, of course, in Massachusetts and, but not in, not in Rhode Island. It, it’s a tolerant, it was a tolerant state. So tolerant that its neighbors sometimes said it was the sewer in a sink to which all the heretics and rouges and rascals had settled. [laughs]

Lisa Berry Drago: As vampire traditions made their way around New England at large, Rhode Islanders might have been the perfect sponge to soak them up. One case from 1784 is a good example of how these ideas could spread. Records state that a foreign quack doctor convinced a town official whose family was dying of consumption to try a vampire remedy.

Michael Bell: We know about this incident because an- another town official named Moses Holmes wrote a very scathing letter right after this event to the local newspaper, uh, saying, warning people to be aware of this foreign quack doctor who’s going around saying he can cure consumption.

Alexis Pedrick: Clearly not everyone was pleased, but many people listened to these quote, unquote, “Quack doctors,” and made the practices their own, taking what they needed and leaving the rest.

Michael Bell: They weren’t bringing with them the entire vampire tradition, which was very elaborate in Europe about how, how does one become a vampire, why does one become a vampire, how do you prevent it from happening and so on and so on. So, he’s just bringing a cure. “You got consumption. Here’s, here’s what you do.” And, and that’s what he was selling and that’s what people were basically buying. So, you know, the pragmatic Yankees going like, “Yeah. Well, I don’t care about all these other details. Just tell me what I have to do to stop this problem and I’ll do it.” It’s, it’s a last resort.

Alexis Pedrick: One interesting thing to note is that most New Englanders, including the Brown family, never actually used the word vampire but this is besides the point for Michael Bell.

Michael Bell: I’m looking at the procedures involved, not the terminology, you know, what’s in a word? A vampire bite by any other name would be just as deadly. So, no. They didn’t call them vampires, but when you look at the rituals that were being performed, basically they’re identical to the vampire rituals that from Europe. Going to the graveyard, looking for s- unnatural signs, often liquid blood in the, in the vital organ. And then what you do next exist in variation, which indicates to me that’s it’s part of folklore, because it didn’t circulate in long enough to become localized that different communities will take these rituals and adapt them and change them to suit their own needs.

Alexis Pedrick: The ritual used on Mercy Brown was pretty typical. They cut out her vital organs, burn them, and fed the ashes to her living, sick brother, but there were variations on this old time remedy. Sometimes, the sick person inhaled the smoke instead of drinking the ashes. In some parts of Europe, you burn the entire corpse. There were also variations in how people believed the vampire was haunting family members and exactly how they were stealing their vital energy and these were different from the vampire tropes most of us are familiar with.

Michael Bell: Most of our ideas about vampires we think, “Well, yeah. It was the first one,” because then that one’s taking down the others, but in the New England tradition, it’s usually the last to die. Now, whether there was a serial kind of [laughs] of this evil think is going from one corpse to the next to keep maintain, uh, you know, as the corpse decomposes, than I’ve got to find a fresher corpse so I’m going to the next, to the next, to the next.

Alexis Pedrick: In just about every vampire movie, there’s a scene where the vampire leaves the grave in bodily form to hunt its victims. This was not the case in the New England tradition. Not only was the term vampire absent, but so was any description of a corpse actually leaving the grave to do, well, anything.

Michael Bell: However, it was killing relatives, it was doing it by sympathetic magic, you know, from a distance. It was, uh, a vital current existing between the dead relative and the living relative. In some cases, it’s described as an evil spirit of some sort or evil angel inhabiting the corpse.

Alexis Pedrick: So, it wasn’t like Mercy Brown herself was evil. She was just an empty vessel who was inhabited by an evil force and no one really questioned why. Why Mercy?

Michael Bell: Well, that was never, as far as I know, uh, addressed.

Lisa Berry Drago: At this point in our reporting, we faced a reckoning. These New England vampires, the Mercy Browns, the J.B. 55s, they’re clearly not the same as the vampires we know and love. They’re frightening, not alluring. They didn’t have to be invited into your house before drinking your blood and there was no consensus on how or why they became vampires in the first place. At a certain point in the vampire trajectory, there had to have been a split. How did we go from the horrors of consumption and death of loved ones to worrying that those same loved ones were killing other family members to finding vampires intriguing, even sexy? To help explain this shift, we turned back to our neighbor and vampire expert, Edward G. Petit.

Chapter four. When did vampires become sexy? When the COVID pandemic started, Ed Petit began hosting a weekly Zoom event called Sundays with Dracula. He did it from his home study, dressed in a three-piece suit, drinking a cocktail and smoking a pipe. He showed up to our Zoom interview in the same getup and even brought his favorite drink.

Edward G. Petit: Port wine cask whiskey, so it was whiskey that was stored in a port wine cask to give it a little more flavor and it turns it a little reddish and then it’s also Heering cherry liquor, uh, which is absolutely delicious and I love it and I call it the happiness you bring, which is a take on what Dracula says when you enter his castle. You know, “Welcome to my house. Enter freely, go safely, and leave something of the happiness you bring.”

Alexis Pedrick: Oh, when you say the word vampire to us, here’s who we think of. Brad Pitt in Interview with a Vampire. Edward Cullen from Twilight. I mean, everyone from Twilight.

Lisa Berry Drago: Eric Northman in True Blood, Angel, Spike, Darla, and Dru from Buffy, Nandor the Relentless, now Joan, Laszlo, Viago from What We Do In The Shadows, Mitchell from Being Cuban, Selene from Underworld.

Alexis Pedrick: And of course, Wesley Snipes from Blade.

Lisa Berry Drago: What have all these vampires have in common? Well, they’re hot, at least by Hollywood standards. Hollywood’s made it very clear that vampire equals sex. Even Bela Lugosi in the 1931 film version of Dracula had it going on, but the vampires of old legends did not start out this way.

Edward G. Petit: Before Dracula, vampires are creatures that kind of dig their way out of their graves, their, they, they smell of decay. They’re certainly not attractive. It’s not like they’re coming to seduce you. They, if, they’re, when, when you read descriptions of them and use old folklore accounts, it’s almost as if the vampires are more like zombies to us, like the George Romero Walking Dead kind of zombie. It’s far more what is, it seems to be what they’re describing as a vampire.

Alexis Pedrick: Vampires, like every monster in every monster story are a manifestation of a culture’s anxieties.

Michael Bell: Monsters are meaning machines, I heard one critic call them once, um, that they take these things from whatever contemporary culture they, they’re, that they’re birthed in and, and, and, and then, and they, the monsters carry our anxieties.

Alexis Pedrick: And what’s more anxiety-inducing than death itself?

Michael Bell: People were trying to figure out what was happening with certain disease outbreaks in small communities, but also, but also try to answer questions of what happens with dead bodies and why do they look this way? Um, but the sex thing with vampires. Now, see, I don’t think vampire stories are about death anymore. I think the vampire stories are now about sex. That’s what the anxiety is in a vampire story. It’s about the threat of the, the kind of erotic in, in our lives.

Alexis Pedrick: Bram Stoker published Dracula in 1897 and it became the seminal novel about vampires but there is actually an earlier one called The Vampyre, with a y, published by John Polidori in 1819, that Ed says points to the first attempt at making vampires sexy. His vampire wasn’t a hairy, dirty beast. He was an elegant yet sinister aristocrat and he was based on the rock star poet of the time, Lord Byron.

Lisa Berry Drago: And there’s no one sexier than Lord Byron. Stoker tries to make his vampire more beast-like than Polidori’s, but he’s still an aristocrat and, really, once it becomes a play and then a film, it’s all over.

Michael Bell: But as soon as people start adapting it, they’re like, “No, no, no. We want our vampires sexy.” And they start looking and acting like, or at least well-bred, beautiful versions of us.

Alexis Pedrick: I know we’ve just taken pains to explain how the original vampires were monsters and movie vampires are sexy, but there’s actually another important connection we need to point out here. We’ve told you all about the horrors of tuberculosis, but somehow because humans never fail to draw the most unlikely of connections, tuberculosis was also considered at the time, of all things, kind of glamorous.

Carolyn Day: In its early stages, tuberculosis seemed to enhance those things that were already considered attractive in women. So, for instance, the idea of pale skin, rosy cheeks, wide, sparkling eyes don’t sound too bad. Uh, but they’re also, um, symptoms of the consumptive disease process.

So, my name’s Carolyn Day. I am an 18th and 19th century British historian and historian of medicine and my specialty is actually the history of consumption or tuberculosis, as we would now call it, um, primarily in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and its connection to fashion and beauty.

Lisa Berry Drago: That’s right. Before there was 1990s heroin chic, there was 1890s consumption chic. It was the most glamorous wasting disease of the Victorian era.

Alexis Pedrick: Remember Michael Bell’s chart comparing consumption and vampires? There could also easily be a chart comparing the symptoms of consumption and the attributes of idealized white feminine beauty at the time.

This was not surprisingly all contingent on race and social class. If you were white and wealthy, consumption was seen as glamorous and attractive, but if you were a person of color in a lower social class, it was nothing of the sort. In fact, it was seen as an entirely different disease. But for those in the bourgeoisie, there was a strangely positive spin to having it.

Carolyn Day: So, if you were already beautiful, it would make you more beautiful, more ethereal. If you were, eh, kind of average, uh, they thought that it could actually improve your beauty and you see this both in the medical treatises and in the, um, like literature dealing with beauty and fashion.

Alexis Pedrick: And here’s where we get right back to vampires.

Carolyn Day: And there are actual, um, medical treaties that conflate consumption and vampirism. So, um, in 1830, there is a treatise on pulmonary consumption, um, and, and they use that sort of metaphor for consumption. It says, “Consumption, like the vampire, while it drinks up the vital stream, fans with it swings the hopes that flutter in the hectic breast. The transparent colors that flit on the features, like those of the rainbow on the cloud, are equally evanescent and leave its darkness more deeply shaded.”

Alexis Pedrick: If we’re ruining vampires for you, we’re sorry, but we’re here to tell you that this whole time you’ve been gazing at Edward Cullen’s beautiful face, you’ve been romanticizing a look based on someone dying of tuberculosis. That’s what the whole modern vampire look is about.

Lisa Berry Drago: Except for the sparkling. That’s new. Stephanie Meyer’s unique contribution to the vampire aesthetic. But there’s something else that makes vampires alluring to us in the 21st century that was absolutely horrifying to people in the olden days, the fact that they didn’t die.

Alexis Pedrick: When we first started talking about this episode, the thing that stood out to us was, well, immortality, because there’s always this tension about immortality in vampire movies. The person who’s about to get turned is like, “Yeah. Make me a vampire. Let’s go. Live forever? Be powerful and strong, sexy, never get old? Sign me up.” And the vampire’s always like, “No. You can’t. You won’t have a soul. I don’t have a soul. Woe is me.”

Lisa Berry Drago: I’m not saying that I would definitely choose vampire immortality if I was in, you know, Bela’s position, but I think I would at least consider it. I mean, I would definitely be intrigued by the possibility. But, as it turns out, this was positively unappealing to people in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Edward G. Petit: And it’s the thing about vampire stories now that we find to be, uh, attractive. “Oh, wait. I could live forever and be beautiful?” That’s tempting. In, in vampire stories of the 19th century, that is terrifying. People think that, “I would never die?” And they are horrified by the fact that they would be immortal. Um, now, we want, we all want immortality. I wa- I want immortality. I want to read every book I own and it’s going to take me like hundreds of years to do that.

Alexis Pedrick: There’s a lot of factors for this drastic discrepancy in world views from century to century but one of them is really Christianity.

Edward G. Petit: It’s, it’s very much a religious response and that the purpose of life is to one day be in paradise. Um, uh, and, and this is at least this Christian world view in, in, in, in Europe and in most of where we’re talking about, these vampire stories. Um, you want to die and be with God, um, and, uh, that’s, that’s the point of life and so if you’re immortal, that means you never are going to be with God, you know, and that’s not, that’s … You’re supposed to be.

Um, and, and also that, that, that staying young and beautiful just seems so unnatural to people who had no way of really doing that. Like, we have all kinds of medical ways and, you know, surgical ways of, of staying young or, at least, we think we’re staying young but at least the appearance of, but that’s just … Nobody can even imagine that, you know, uh, up, up until the 19th century.

Alexis Pedrick: But, of course, the curse of vampirism isn’t just about living forever. It’s about having no soul. In vampire myths in the Christian West, vampires lose their souls when they’re turned, so either they crumble to dust or go to hell when they die. Not exactly a sweet gig. There are even accounts of young people who are terrified that they turn into vampires after their deaths.

Michael Bell: In one case, a young woman is begging her parents. She knew she was dying of consumption, that after she died, to promise her that they would remove her heart and burn it so she could save her sisters. I mean, she’d heard about the stories and so, her parents consented and that was done. Uh, and it’s heart rending.

Alexis Pedrick: No one wanted to live forever. They wanted to die when they were supposed to and vampires were a monstrous threat. You certainly didn’t lust after them or desire to be one of them. Our sexy vampires from film and literature were irrelevant to 19th century New Englanders. They were battling them in real life or so they believed.

Chapter five. Homeopathic magic.

Lisa Berry Drago: So, did these rituals work?

Edward G. Petit: Well, that’s a good … [laughing] No. That, uh, that’s an obviously, uh, a good question. I, I ran the statistics on this. I don’t have them available at my fingertips, but in, in most cases, uh, someone else died after the ritual is performed but then, there are a number of cases where one person they were trying to save died but the rest of the family was spared so, I mean, was it a success or not a success?

Here’s a stat that kind of helps explain that. If you took the advice of a medical profession and did whatever they suggested you do, you died just as often as you did if you did nothing and just as often as you did if you perform the so-called vampire ritual. So [laughs] basically at that time, no one had it down. No one could, could cure you.

Alexis Pedrick: In some ways, the solutions offered up by medicine were just as much based in fantasy as the vampire rituals. One popular treatment was a good old change of climate, i.e. go somewhere with fresh air and hike or ride a horse to restore your health.

Michael Bell: Edwin was sent away to Colorado Springs, which is where people were going at that time. That’s how the whole city of Colorado Springs got started was consumptives were going there to try, try to, you know, a change of climate, a dry climate, a, a warm cli- Whatever would help you, uh, overcome the disease. Well, it didn’t help Edwin.

Alexis Pedrick: It didn’t really help anyone. In fact, what it mostly did was spread tuberculosis around to those places. The logic wasn’t entirely faulty. Dense urban centers and stuffy living quarters did contribute to spreading TB, but once you had it, the fresh air wasn’t really going to do you any good. The reality was sometimes people got better but usually they didn’t.

Michael Bell: Some people recovered, just like all diseases. For some reasons, some people were more immune to it, were able to fluff it off to recover. There were a lot of people infected with tuberculosis, thousands and thousands and thousands who never showed symptoms.

Lisa Berry Drago: Other proposed treatments for TB were warm sea air, seaweed placed under the pillow, and the milk of a pregnant women and shockingly, none of those cured it.

Alexis Pedrick: Meanwhile, it you look closely at the individual elements of these vampire remedies, even though they sound crazy, they’re actually also based in empirical observation.

Michael Bell: They understood contagion in a sense. They knew that, you know, in that sense, death was contagious.

Alexis Pedrick: Take, for example, one way of spotting a vampire in a graveyard, by looking for a vine growing from coffin to coffin.

Michael Bell: And if the vine reached another coffin, then another person in the family would die. So, that’s a kind of transference of the disease there. The vine is, it’s acting as a transmitter of the disease and some people talk about a miasma, an evil vapor. And, again, all of this goes back to the, the notion of contagion. So, it’s not, it’s not crazy irrational. It’s a reasonable interpretation of what was going on, especially in light of the fact that the medical community had no clue at that time.

Alexis Pedrick: Remember how George Brown’s friends and neighbors had to convince him to perform the vampire ritual? Well, it turns out George Brown himself did not actually believe in the vampire theory. He definitely didn’t believe that his own daughter was a vampire preying on others, but he did understand that his neighbors had a valid personal stake in doing whatever they could to stop the threat from spreading.

Michael Bell: Because, if you didn’t stop it in your family, then it’s going to come and take our family. So, with the kind of social responsibility that George Brown felt, to his friend and his family to do this, even though he found it repugnant. Who wouldn’t? Just think about it.

Alexis Pedrick: And then, there’s the ritual itself. Whether it was drinking a potion made from the ashes of a burned heart or inhaling the smoke, all in the name of healing.

Michael Bell: What we’re talking about is, is a form of cannibalism, but it’s, it’s not so crazy to me as, as it might sound. I mean, it’s sort of like an inoculation. It’s reasonable. You take something that’s corrupt, that’s evil, that’s diseased, you burn it, which is a purifying ritual, which gets rid of the evil, and then you take the remains of that and put them in your body. It’s a kind of vaccine.

Let’s not pat ourselves on the back and break our arms doing it over how smart we are. We’re no more intelligent than our ancestors who did these things. We have more knowledge which makes us seem smarter, but we’re really not and the people who were performing these rituals were just as logical and intelligent as, as we are.

Edward G. Petit: And when you don’t have these answers, you, you have to go with what the available evidence is, uh, and then they go and dig up a body and the body’s kind of bloated and it’s got blood around the mouth and you think, “Whoa, whoa! They, of course, it must have been feeding on people. What … How … It doesn’t get bigger after, after they die.” Uh, people have the misnomer that the hairs grown and the nails grow. Well, it all makes sense. It’s like a forensically sound way of figuring out what’s going on but it’s all wrong. [laughs]

Alexis Pedrick: This past winter in January 2021, Michael Bell and archeologist Nick Bellantoni were featured in a Smithsonian documentary about J.B. 55. That quote, unquote, “Vampire” discovered in Connecticut when some boys collided with a skull in a gravel pit. Nick Bellantoni spoke the last line of this documentary and it was eerily prescient, considering that all of the filming took place in 2019, before the COVID pandemic fully erupted.

Michael Bell: He said, “Think about this practice, you know, in a modern context.” He said, “God forbid a pandemic hit us where we cannot stop the deaths. People are going to do irrational behaviors just out of fear and love,” and that’s what it was all about. They were asking the same questions then that people are asking now. “What’s going to happen to us? Uh, will we be safe? What should we do? You know, what can we do?” And these are the questions that are generated by the fear and uncertainty that accompany, you know, all epidemics regardless of the, of the time or the place. And if these concerns aren’t adequately addressed, if the answers provided don’t lead to acceptable resolutions such as not dying primarily, then people look for answers elsewhere.

Lisa Berry Drago: The great New England vampire panic finally ended when medicine finally provided answers that led to those acceptable resolutions, but that took a while. The first step was figuring out what really caused tuberculosis in the first place. Shockingly, it was not damp soil or too much dancing. It was a bacteria, the one we mentioned earlier, Mycobacterium tuberculosis humanis and it was identified by a German microbiologist named Robert Koch in, and here’s the twist, 1882. That’s 10 years before Mercy Lena Brown died of consumption and one year before her mother and sister did.

If you’re shocked by this twist, that is a perfectly reasonable reaction. To be honest, we were shocked, too, but one of the tragic things we’ve learned this year is that identifying a threat is only the beginning of the battle. Public health measures around sanitation certainly helped contain the spread but didn’t lead to an immediate cure. That didn’t happen until 1942, with the antibiotic streptomycin. That’s worlds away from sequencing a virus and having a vaccine in development months later.

The latest vampire exhumation Michael Bell found was in the mountains of Pennsylvania in 1949, but that was an outlier. Something else had helped end the vampire practice much earlier.

Michael Bell: The practice of embalming the corpse was becoming more and more in vogue, you know, thanks to the technology, uh, increasing during the Civil War and then Lincoln’s body had been involved, embalmed so that he could go from Washington to Springfield, Illinois by train and, and stop and people could, you know, pay their respects to his corpse. So, if you, if you drain the blood out of a corpse and then fill it with some sort of chemical, it’s, you’re pretty much disarming it as a potential vampire threat, because no evil thing is going to inhabit a corpse when it can’t get blood, uh, according to the theory. And so, those elements came together to really spell the, the, the demise of the practice.

Alexis Pedrick: Who knew embalmers were the real Van Helsings?

Lisa Berry Drago: We were drawn to this story by the wild historical medical practices, but let’s be real. There’s always going to be a new, frightening problem on the horizon that we’ve never had to deal with before and we don’t understand and we don’t react very well to. The story is as much about collective trauma and collective responsibility as it is about burning hearts.

Alexis Pedrick: Think about all the things we did in the beginning of the Coronavirus pandemic to keep ourselves safe, wiping down groceries, singing Happy Birthday the whole time to make sure we were washing our hands long enough. And all of these things helped and they all contributed to the collective good, but we also did them because we were scared, because we didn’t know what was out there and, you know, how to protect ourselves.

Everett Peck: Well, years ago, you didn’t have medicines. You didn’t have nothing.

Michael Bell: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Everett Peck: You, you, you, you had to figure out your own.

Michael Bell: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Everett Peck: Because they were self-independent people. Everybody lived here. There was no such thing as relying on somebody. You did it yourself.