Anthony Comstock was never much fun.

During the Civil War, he watched with horror as his fellow soldiers drank, caroused, and otherwise debased themselves. Soon after the war he moved to New York City, where he encountered quacks, con artists, sex workers, and moral degenerates of all types.

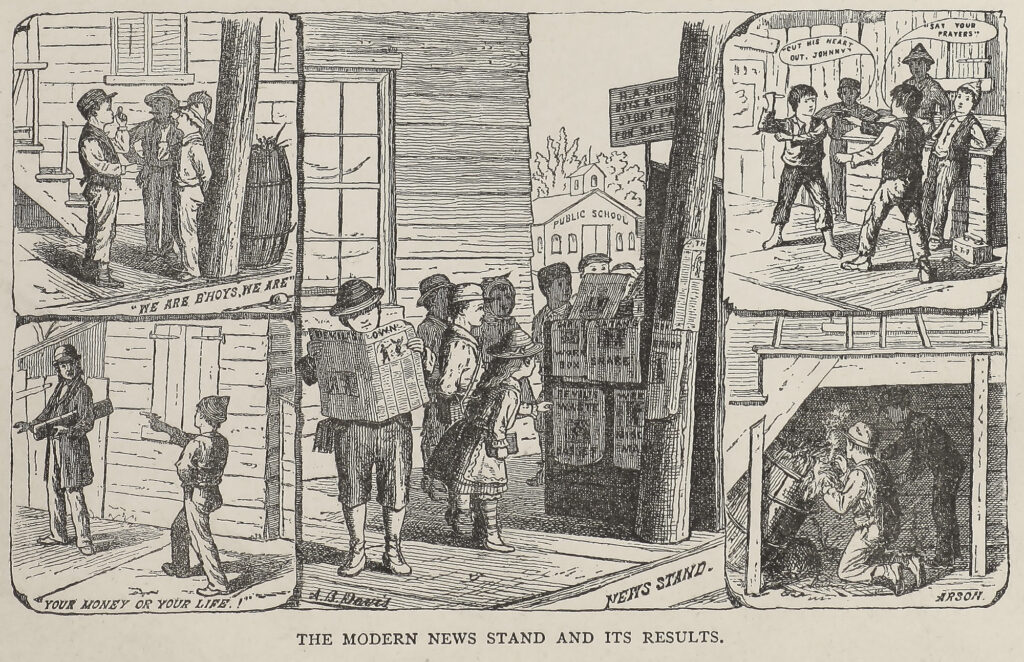

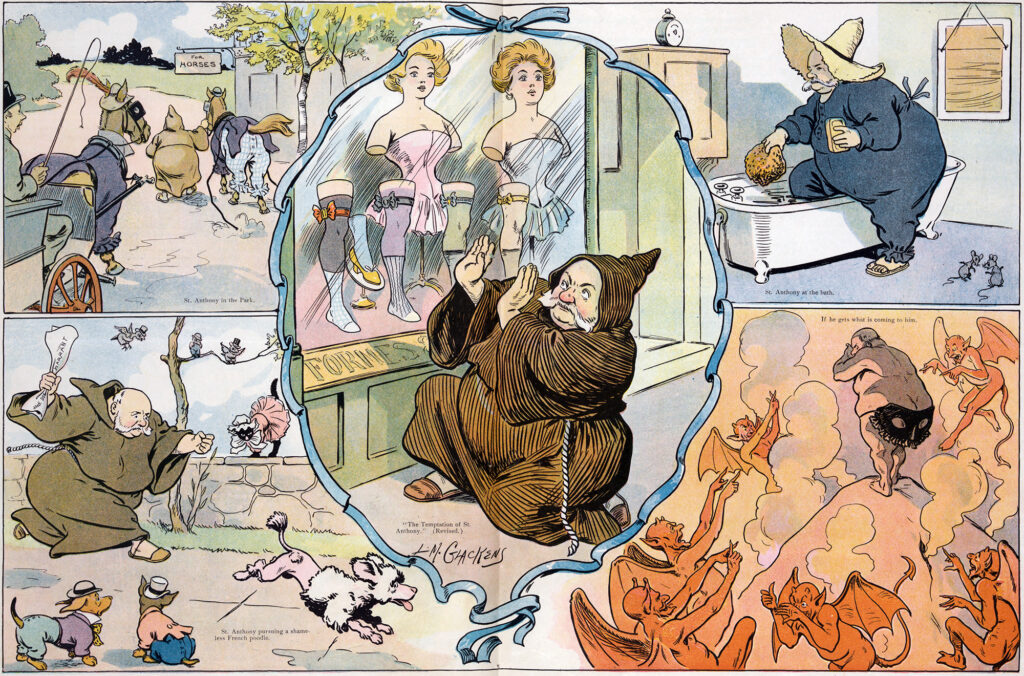

Perhaps most troubling to Comstock was the sheer volume of young men engaging in debauchery—buying lurid dime novels, smoking tobacco, having rampant premarital sex. He sought refuge in the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), where he railed against the evils of pornography, bank fraud, gambling, infidelity, women’s suffrage, and anything else he decreed a vice.

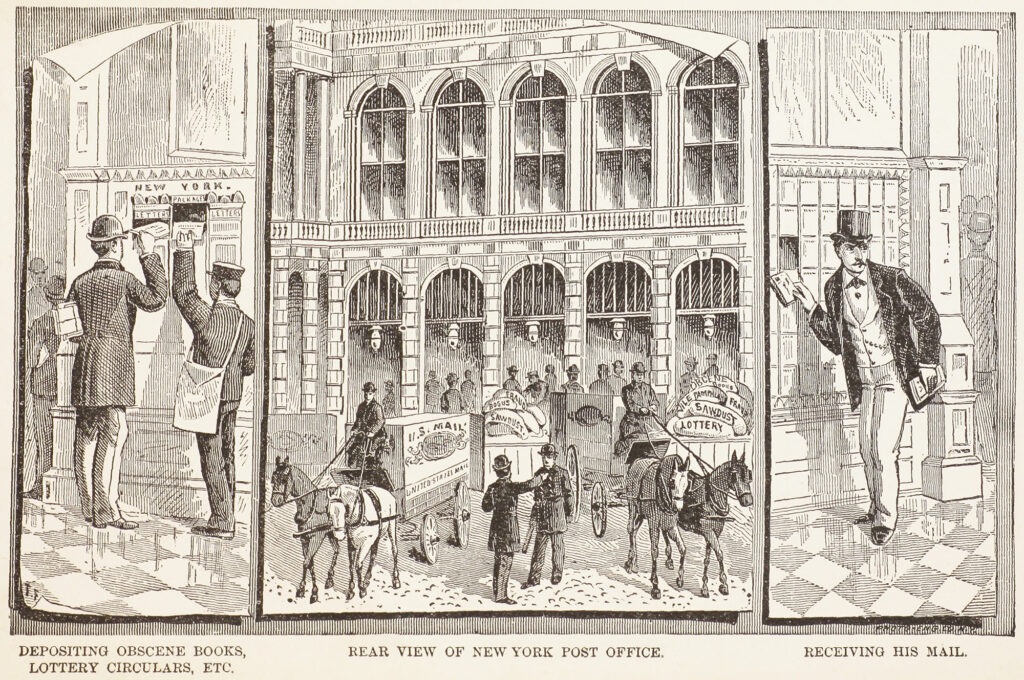

Five years of fighting for Christian morals with the YMCA established Comstock as a force within the anti-vice movement. In 1873 he created a vigilante organization dedicated to maintaining public decency. That same year he coauthored and convinced Congress to pass the Comstock Act, which prohibited the mailing of “obscene” materials, including pornography, sex aids, contraceptives, abortifacients, or any advertisement or correspondence referring to them. He was appointed special agent for the postmaster general, and from that position he set the machinery of the U.S. Mail against the malevolent forces he believed were corrupting the nation’s youth.

To Comstock, there were few forces as dangerous as Madame Restell.

Restell, also known as Ann Lohman, was among New York’s most enterprising women. She got her start in the 1830s, selling home remedies for unwanted pregnancies and other problems out of the city’s disease- and crime-infested Five Points neighborhood. By the time Comstock set his sights on Restell, financial hardship was far behind her. From a brownstone mansion on Fifth Avenue, she catered to a disgraced and often wealthy clientele that stretched across the country. Like her affluent clients, she traveled in horse-drawn carriages, wore fine silk gowns, and oversaw a large household staff. Unlike most of her clients, she also managed land holdings and a business with satellite offices in Philadelphia and Boston.

Madame Restell had built her empire by addressing problems most doctors would not. It infuriated Comstock, and he was determined to tear that empire down.

On the frigid night of January 28, 1878, Comstock set out to finally do it, using a ploy he had turned to often. Posing as a customer, he rapped at Restell’s mansion door and came face-to-face with his nemesis. Restell escorted her visitor to a basement room, where he requested “any article for the prevention of conception.” After evading further questioning, Comstock was handed a small package of pills. Restell assured him they were effective 9 times out of 10, and if they were not, he should have his companion make an appointment for further intervention. He put $10 in her hand and walked out.

Two weeks later, on February 11, 1878, Comstock returned to Restell’s doorstop with a search warrant and two police officers in tow. Officers found her home littered with pills, powders, pamphlets on reproductive health, and other “foul materials.” She was ordered to police court, where a judge refused to accept bail, instead committing her to the city jail known as the Tombs in her old Five Points neighborhood.

On her release a few days later she flashed a defiant public posture, but she knew her prospects were grim. She had been tried and convicted twice before, even serving a year in prison on New York’s Blackwell’s Island. This time around, her punishment was bound to be far worse, the culmination of decades of public outrage and moral disgust.

Comstock and his allies had cast her as a fiend, demon, wretch, monster—the wickedest woman in New York. Her professional pursuits earned her comparisons to dissolute and powerful women of the distant past, including Valeria Messalina and Poppaea Sabina, ancient Romans vilified for their feminine wiles, promiscuity, and deceitfulness.

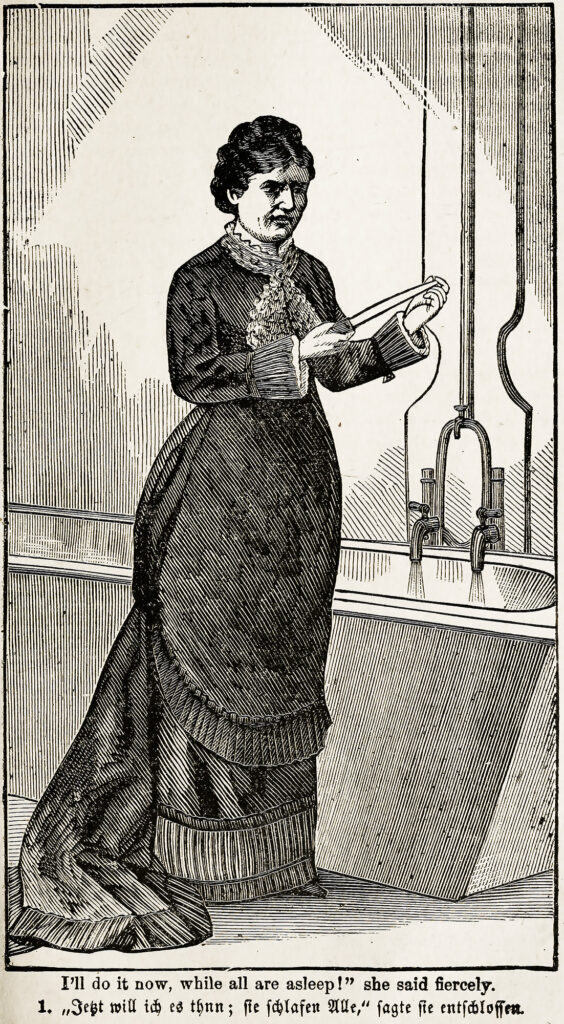

In March she was indicted for the possession and sale of improper drugs and medicines. She pled not guilty but was never tried.

“Madame Restell, otherwise known as Ann Lohman, cut her throat with a carving knife, and was found dead in her bathtub early yesterday morning,” reported the St. Johnsbury Caledonian on April 5. “The estate which she has left is estimated to be worth half a million of dollars. She will be remembered as a noted abortionist.”

The brutalities 19th-century women often faced at the hands of underqualified gynecologists drove them into the arms of practitioners like Madame Restell. The appeal of having someone who empathized and addressed women’s health as a legitimate medical concern was powerful, but it would take until 1849 for the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. During a time when the medical field was reluctant to accept women into its ranks and saw women’s bodies as naturally flawed, people like Ann Lohman—hidden behind fake names and fake credentials—found lucrative openings serving women outside the establishment.

Madame Restell’s rise coincided with and, perhaps, was fueled by a period of constant flux in women’s health care in the United States.

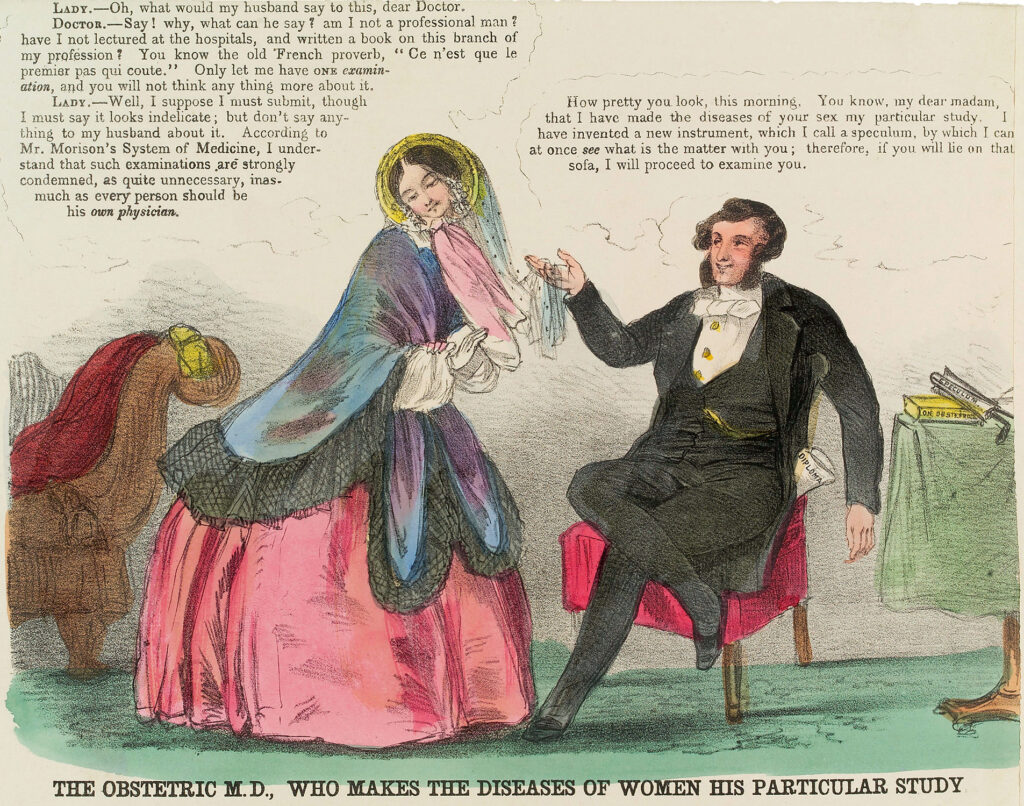

By the 1840s medicine had begun professionalizing, but gynecology was slow to follow. Specializing in gynecology was generally frowned on—it was dismissed as women’s business and deemed unsuitable for dignified men. Childbirth was the realm of midwives, and midwives had no place in the medical field. As a result, men studying medicine were given sparse training on women’s health and reproductive care. Those who chose to specialize in the field were often seen as perverse and lecherous‚ scoundrels preying on feeble women.

Despite this prejudice, some physicians still chose to specialize in women’s disease, though the training they received was often rooted in speculation instead of tested observation. In 1848 Charles Delucena Meigs, chair of obstetrics and women’s diseases at Jefferson Medical College, published Females and Their Diseases, an extensive chronicle of the fundamental sensitivity that predisposed women to illness. Meigs’s explanations of disease were accepted as medical fact, and they contributed to a growing mass of misinformation around women’s health and well-being. As new generations of physicians picked up Meigs’s work and the work of those he influenced, women’s health issues were ascribed to a fundamental and downright normal weakness.

Other forces in the medical establishment conspired to disempower women. The American Medical Association (AMA) was founded in 1847, and one of its first initiatives was to advocate for the criminalization of abortion nationwide, pushing midwives further to the sideline. At the same time, the AMA began cracking down on quacks peddling ineffective and often dangerous nostrums to the public. These actions were part of a larger objective to formalize medicine and create structured criteria around who could practice it. Members were deciding who counted as a real physician—a title that had been thrown around more casually before the 1850s.

In the years around the Civil War, a wave of social change rocked the United States and, in turn, challenged the medical establishment’s treatment of women. Free love advocates rallied around the removal of state control in decisions concerning marriage, birth control, pregnancy, and relationships in general. Joining them were suffragists, who, in addition to calling for women’s ability to vote, urged women to seize control of their health and well-being.

This threat to social and professional norms compelled doctors to use their medical authority to diminish the authority of the women who critiqued them. As Meigs and countless other doctors saw it, women were fundamentally weak and couldn’t be trusted to vote, work, or learn.

In 1873 Edward Hammond Clarke, a physician and professor at Harvard Medical School, published Sex in Education, a book dedicated entirely to the “scientific” reasons why women shouldn’t be allowed to attend his medical school. Clarke argued that women who studied like men risked “neuralgia, uterine disease, hysteria, and other derangements of the nervous system.” Such women, he warned, would “give birth to a feeble race, not of women only, but of men as well.”

Another Civil War–era physician, Silas Weir Mitchell, became famous for his rest cure—a strict regimen of lying in bed, isolated from all social contact, with no activity of any sort in order to relieve neurological distress. Mitchell began experimenting with rest cures on traumatized veterans and soldiers in Philadelphia during the war. While many of these patients experienced relief, he soon began prescribing the treatment to the women who sought him out with complaints of unbearable pain. He attributed the severity of the pain to the biological weakness of their sex and believed switching up their scenery and diet would be sufficient to ease their distress.

Mitchell treated a long list of genteel patients, including writers Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Virginia Woolf, who referenced the lackluster results of his treatment in The Yellow Wallpaper and Mrs. Dalloway, respectively. Mitchell wrote his own elaborate novels, contributing to a booming genre of medical and fictional literature fixated on women’s fragility. His stories, frequently based on his female clients, featured vacuous, invalid women in anguish—crucially, they were never actually diseased.

For the medical establishment, menstruation and the notion that women were unable to control the beginning or end of their cycle was seen as the root of female invalidity. So when all other interventions failed, the only solution that remained was to remove the very source of menstruation.

Enter Robert Battey. As gynecological surgery became its own specialized field in the second half of the 19th century, more and more physicians began prescribing invasive surgeries as remedies for a host of female illnesses. Battey implored other surgeons to consider the total removal of ovaries—even if the ovaries themselves were healthy—to cure everything from menstrual pains and irregularities to hysteria. His small-scale study into the efficacy of ovariotomy produced a mixed bag of successes, failures, and one death. (By the 1890s this frightening approach had extended to the uterus as well.)

“It is the great systemic revolution which occurs upon the final cessation of ovulation which I seek to effect and that such result follows upon the complete extirpation of the ovaries is, I think, not to be called in question,” Battey wrote in 1876.

However, many women did push back against such medical narratives around their health.

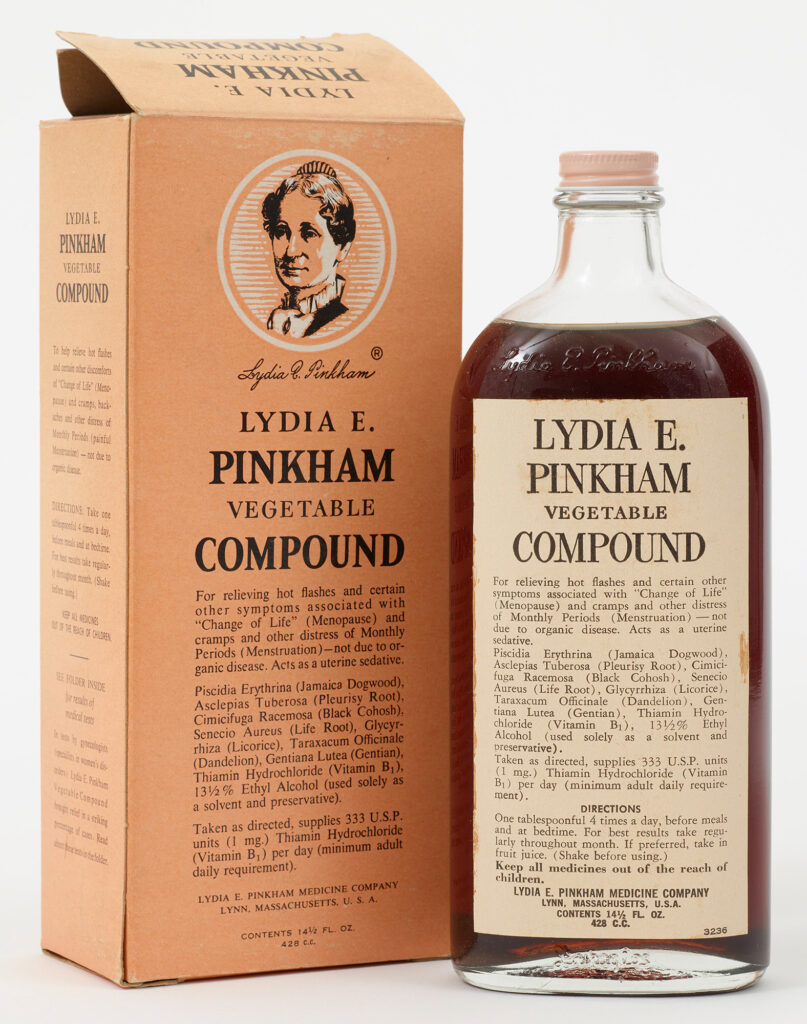

Some began creating detailed educational pamphlets documenting the reproductive health issues they had experienced, how to identify them, and how they solved these problems without seeking a doctor. They exchanged herbal remedies they had learned over the years. This information was frequently shared in whispers between friends and neighbors and from mothers to daughters. But in some cases, women managed to disperse this knowledge on a much larger scale—by creating their own medical mail-order businesses.

“When the organs peculiar to woman are displaced or disordered, and pangs shoot through her like winged, piercing arrows or darting needle-points, man may study of all this in books, or question the sufferer as to the indescribable pain, but all must still remain to him a world of woe ever unknown and mysterious,” noted Lydia E. Pinkham’s Private Text-book Upon Ailments Peculiar to Women.

Born Ann Trow in 1811, Madame Restell was the only daughter of a laborer in Gloucestershire, England. She had seven brothers, started working as a maid at 15, and began selling contraceptives on the down-low sometime after the death of her first husband, Henry Summers, in 1833.

Just two years prior, Ann and Henry emigrated from England to New York. Henry was an alcoholic and barely made ends meet as a tailor. When he died, Lohman was left with an infant daughter to support and poor financial prospects. She took on work as a seamstress, but in their downtrodden neighborhood the competition among seamstresses was high and the pay was low. This was when she met William Evans, the neighborhood quack, who sold an assortment of proprietary pills, powders, and poultices with varying degrees of efficacy. Under his tutelage, she soon began discreetly selling her own contraceptives.

She met and married her second husband, Charles Lohman, a few years later, in 1836. He was a compositor for the New York Herald and a proponent of population control who had published tracts about contraception and family planning. Far from being horrified by her burgeoning enterprise, he encouraged it.

The story goes that he sent his new wife to France to study under her relative, and she returned equipped with a practitioner’s understanding of midwifery and women’s diseases. She adopted a pseudonym, Madame Restell, and launched a business selling pills, powders, and pamphlets on reproductive health out of a clinic in lower Manhattan.

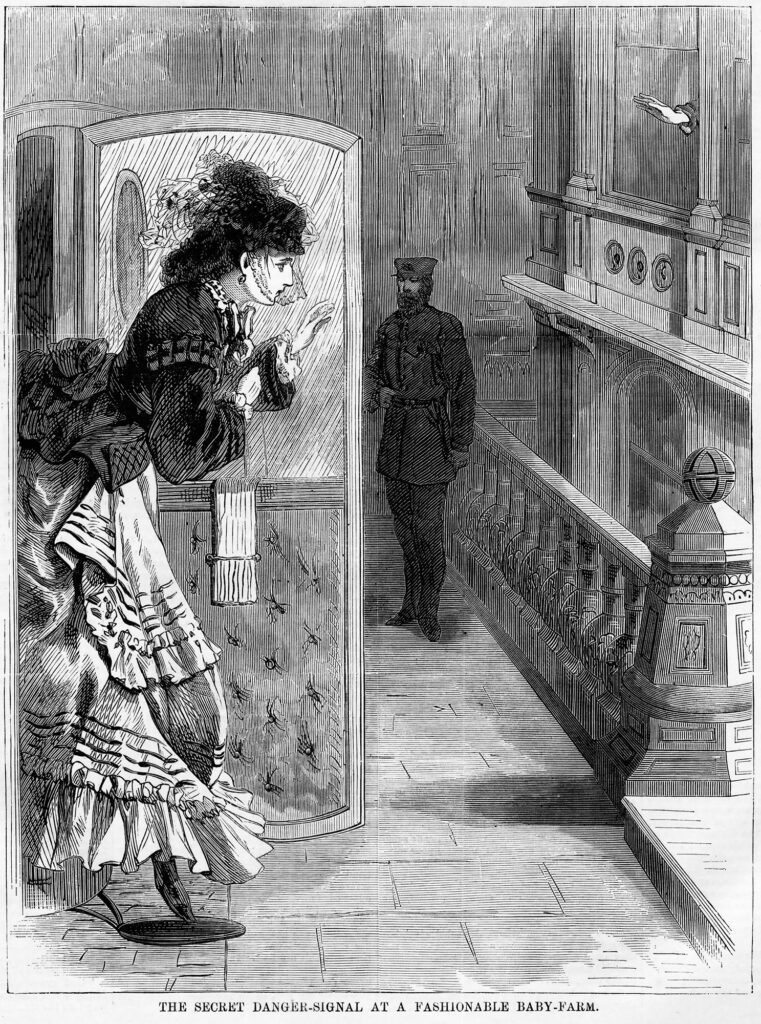

The couple expanded their business, performing surgical abortions on a sliding scale or connecting women to surgeons who would perform the surgery. They also provided housing where unmarried women could wait out their pregnancies while arranging for their children to be adopted.

Throughout her decades of work, Restell experimented with new formulas for her powders and pills. During the 1830s her abortifacients used ergot of rye, which is taken from rye plants infected with the fungus Claviceps purpurea. The fungal spores create hard balls that contain the chemical alkaloids ergotoxine, ergotamine, and ergometrine.

But Madame Restell wasn’t just pulling fungi off a plant and feeding it to her clients; she was adapting treatments that were based in the scientific consensus of the time. In 1813 a Massachusetts physician published his dissertation on the efficacy of ergot in activating uterine contraction during the second stage of labor. Two decades later, the Dispensatory of the United States of America advised the consumption of 15 to 20 grains of ergot every 20 minutes to induce uterine contraction. Madame Restell was simply applying this science to earlier stages of pregnancy, which traditional physicians chose not to do. Ergot of rye had been used by midwives since the late 16th century, and obstetricians continued to use ergotmetrine, a drug derived from it, until the 1970s.

But like medicines used by her physician counterparts, Madame Restell’s formulations could be dangerous, even fatal, when taken in the wrong amount. When consumed, ergometrine contracts the smooth muscles lining the uterus, which induces the contractions necessary for labor or miscarriage. But in excess, the other alkaloids found in ergot constrict arteries, slowing blood flow and causing gangrene of tissue and occasionally convulsions and hallucinations.

The fungus could just as likely induce nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, purging it from the body before it had its intended effect. Fortunately for her customers, Madame Restell’s business ran on the model that if her contraceptive powders and abortifacient pills didn’t work, her clients could always come back to her for a surgical abortion.

By the 1840s Restell was offering liquid medicines that contained oil of tansy and spirit of turpentine. While turpentine can induce miscarriage, it can also cause internal bleeding, vomiting, brain damage, and death.

When Ann Lohman began selling contraceptives and abortifacients, laws around abortion were vague and difficult to enforce. In New York an 1829 ruling deemed abortions performed after “quickening,” the onset of fetal movement, a felony. Abortions performed before quickening were a misdemeanor.

In 1841 one patient’s deathbed confession that she had received an abortion from Madame Restell two years earlier led to a public trial against Lohman. She was found guilty, but her conviction was overturned when, after an appeal, the state supreme court deemed the deceased patient’s confession inadmissible.

Innocent or guilty, the damage was done, and Restell’s reputation as a filthy, villainous crook appealing to the baser morals of weak women was cemented. She was branded “a monster in human shape.” Her practice continued, though under immense public scrutiny. It was only a matter of time before the police came knocking at her door again.

Sure enough, in 1847, Restell was brought to trial for providing an abortion a year earlier. Because quickening couldn’t be established, she was found guilty of misdemeanor procurement and sentenced to a year on Blackwell’s Island.

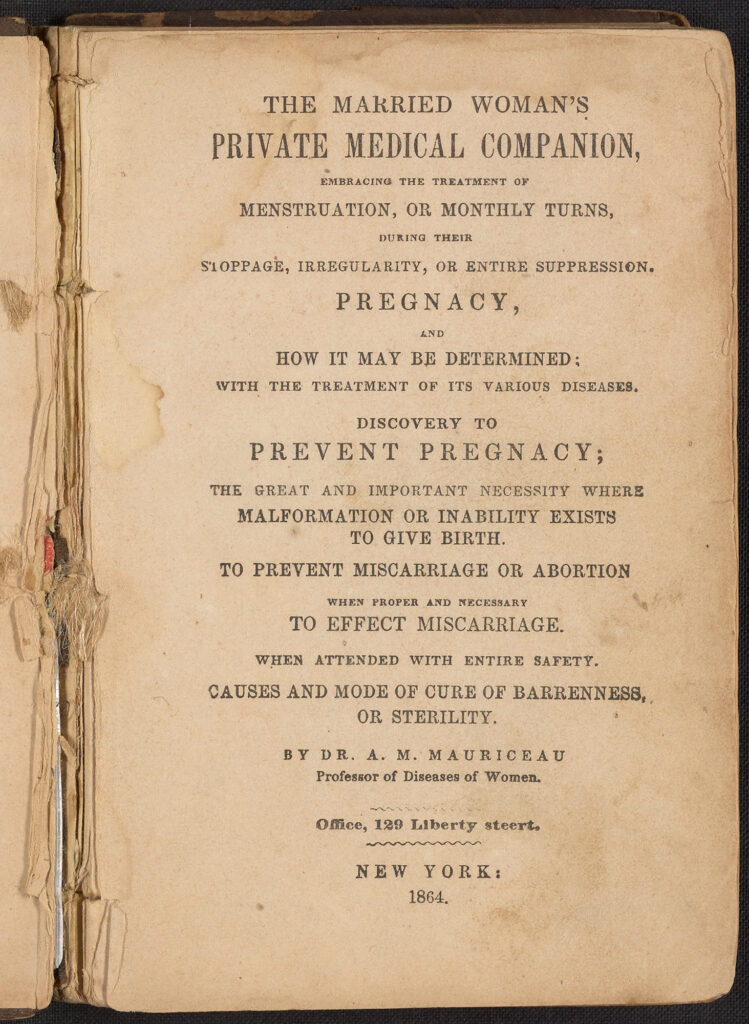

While she was sequestered, a book called The Married Woman’s Private Medical Companion was published by a Dr. A. M. Mauriceau, a pseudonym for either Restell’s husband or brother (or both, working together). Mauriceau was touted as a professor of women’s diseases, and the book explained in detail the symptoms, causes, treatment, and prevention of uterine prolapse, menstrual pain, miscarriage, pregnancy, and infertility. Mauriceau, of course, worked right next to Madame Restell’s office in New York and happened to be a purveyor of many similar mail-order contraceptives and abortifacients.

Some of the remedies on offer were quack solutions. For treating a case of infertility, Mauriceau recommended Morand’s Elixir, which he presented as a miracle remedy.

“The lady being of the most pure and irreproachable character, it may well be supposed that it gave me the greatest confidence in recommending this truly wonderful ‘Elixir,’ in like cases,” he wrote. “Indeed, I am convinced, that if the case is curable, ‘Morand’s Elixir’ is infallible.” He claimed it could also treat incontinence, gonorrhea, consumption, and night sweats for $5 a box (around $160 today).

According to Mauriceau, Morand’s Elixir comprised “the most nourishing, strengthening, and invigorating fruits and plants of Italy,” things that decidedly do not treat infertility. Although it’s unclear what Morand’s Elixir actually contained, other recommended remedies were provably dangerous.

Mauriceau’s advice to “induce menstruation” involved the use of botanicals such as pennyroyal, tansy, and motherwort. The pennyroyal plant had been used for hundreds of years as a cooking herb, medicinal tea, and insecticide, but also as a method to induce miscarriage. The active chemical, pulegone, an oil extracted from the leaves and flowers of pennyroyal and other plants in the mint family, can quickly turn fatal.

For extreme cases of the “immoderate flow of the menses”—heavy menstrual periods, which Mauriceau alternatively called “hemorrhage”—the author suggested six grains of sugar of lead and one grain of opium divided into four parts and taken every three hours until symptoms ease. Lead (II) acetate, called sugar of lead for its slightly sweet taste, is, like most lead, quite toxic, though this wasn’t known at the time. Opium similarly can lead to irregular menstrual periods (thereby technically controlling the menses), but it can also lead to heavier periods as well as infertility, not to mention addiction and all other manner of health problems.

But some remedies were legitimately successful and are still used to this day. Mauriceau’s recommendations to take magnesia and peppermint water for heartburn are still medically sound, as is his advice to take mild doses of Epsom salt “if the bowels are confined.”

Restell’s husband and her brother Joseph bided their time selling the advice of Dr. A. M. Mauriceau during Restell’s prison sentence. Upon her release a year later, Restell swore off all surgical abortions, focusing solely on her mail-order business and boarding house. But she never made her way back into society’s good graces.

Doctors, journalists, and religious activists were vocal about their distaste for her and her business. She was blackmailed, threatened, shamed, harassed, and was always one misstep away from facing the unyielding horrors of the law.

“Madame Restell has in the basement of her establishment a large furnace, which an ill-behaved servant girl has had the temerity to say ‘must be used for burning new born babies,’ ” alleged one newspaper.

“Lechery and lust paid tribute to her pretensions, and as business increased, so did the hopes, the avarice, and the audacity of this woman,” a New York physician chastised.

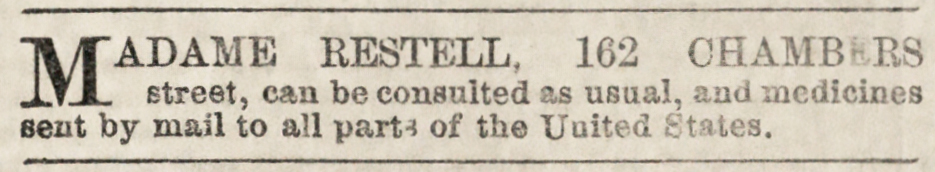

Despite this vitriol, Madame Restell’s extensive advertising campaigns pushed on in newspapers across the country. That fateful morning of her final arrest, she ran her regular advertisement for “Mme. Restell’s sure remedies” on the front page of the New York Herald, offering free consultations at the home address from which she was plucked.

“Everybody is aware of her business and location,” the Helena Herald remarked months after her death. “She cannot be accused of walking in darkness, or shrouding herself in mystery.”

This was not entirely true. Given the social stigma around abortions and reproductive health in general, the ads were covert in how they directed women to her services and used oblique language, such as “obstructions” and “irregularities,” as code for unwanted pregnancies. Her powders were said to resolve “too rapid [an] increase of family.” The intended audience got the message. Restell received letters from across the country asking for medicines and advice. Her business became profitable so quickly that she had to warn patients against fraudulent copycats placing similar newspaper ads.

Indeed, dozens of other enterprising women, none in possession of professional medical accreditation, offered similar services. When doctors failed to take women’s pain seriously or—worse—treated it with extreme, violent solutions, desperate women turned to entrepreneurs like Lohman instead.

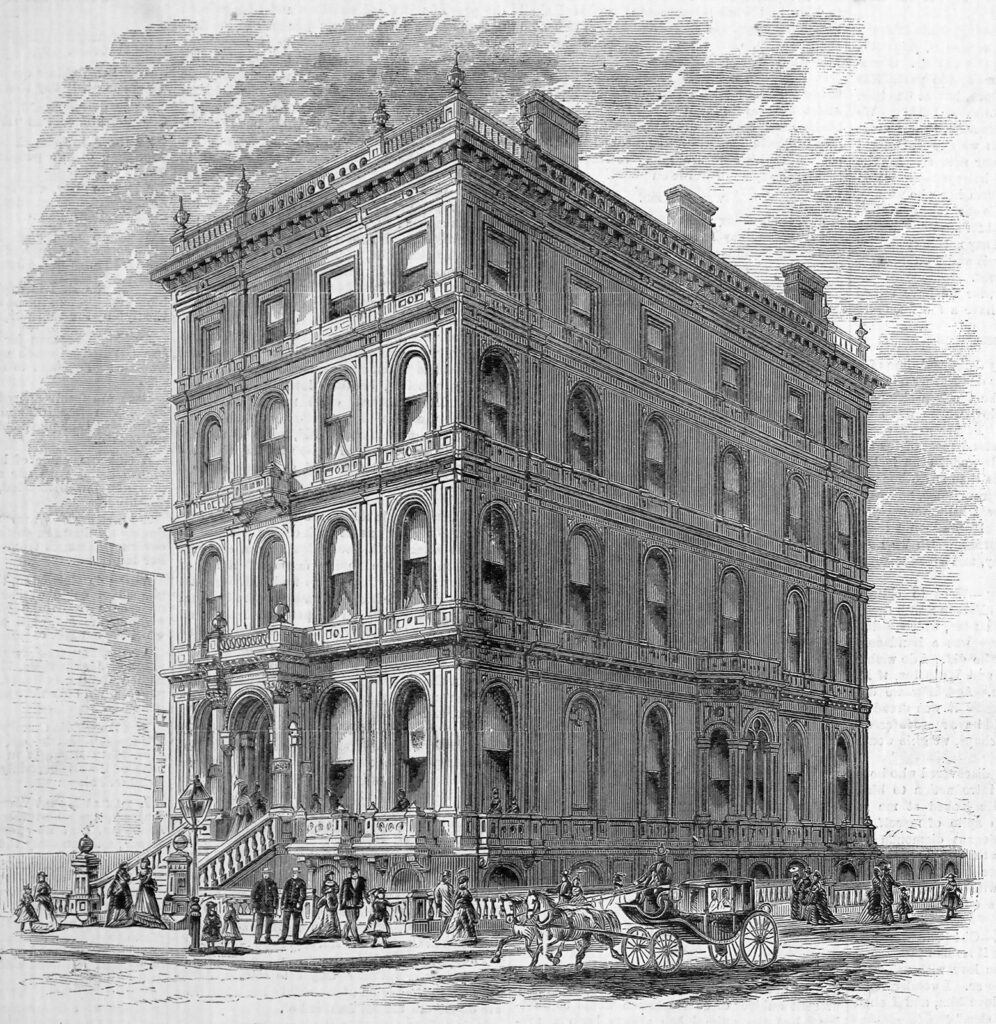

The Comstock Act—with its new, vague definition of obscenity and prohibitions against the mailing of lewd materials—threatened the very existence of mail-order businesses like Restell’s. Their advertisements were placed in newspapers and pamphlets distributed by the postal service. Buyers placed their orders using the mail, and products were shipped through it.

This focus on the postal service was only one step in Comstock’s drawn-out campaign to eradicate sin and immorality in the American public, but it had an extraordinary chilling effect.

Just a few months before co-authoring the Comstock Act, he used his platform to found the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV). It began by preaching to young New Yorkers about the harm created by vice, but it quickly became a vigilante organization that conspired with local courts, lawyers, and police to enforce the Comstock Act.

He shut down literary magazines, raided publishers, and even arrested an art gallery owner for selling reproductions of Alexandre Cabanel’s The Birth of Venus. Between its formation and 1906, the NYSSV seized and destroyed 78,391 pounds of books and sheet stock, 65,279 newspapers containing unlawful and obscene advertisements, and 10,321 boxes of abortive medicines.

At the time of Lohman’s arrest in 1878, it was speculated that Comstock went after her so he could lay claim to a portion of her wealth after her conviction—a sort of reparations to the NYSSV, which was facing a depleted treasury and a decrease in donations. It was more likely a publicity stunt.

Over the course of 40 years Madame Restell had become the face of abortion in the United States and, by extension, women’s interference in the male-dominated medical establishment. Taking her down would have been a blow to midwives, abortionists, mail-order entrepreneurs, and quacks across the nation.

The Comstock Act’s challenges to these mail-order patent medicines did not, however, stifle demand. It was well-known that she “who becomes a mother, when unmarried . . . passes a fiery ordeal, from which she shrinks with terror. If she makes known her condition, a public disgrace awaits her: if she tries to conceal it, she is liable to imprisonment.” Women continued seeking solutions to their unwanted pregnancies far away from gynecologists, even if the businesses they turned to were equally untrustworthy.

Madame Restell wasn’t a doctor, though she referred to herself as a physician. This wasn’t uncommon at the time she started her work. In the 1830s anyone could call themself a physician with no real credentials to show for it. But she and her husband took this lie further—they fabricated her entire trip to France to give her medical skills legitimacy, just as they fabricated A. M. Mauriceau, the doctor who steered patients in the direction of Madame Restell.

Comstock’s motives in bringing her down had little to do with whether her services posed a danger to her patients. To most New Yorkers, Comstock was a religious fundamentalist and a fool, a man so wrapped up in his own self-mythology that he reportedly once shook his badge at a horse, yelling, “Don’t you know who I am? I’m Anthony Comstock!” He was blind to his malignant narcissism, certain to the end of his life that he was a moral crusader, shrewdly rooting out evil.

For a decade after his death in 1915, the NYSSV channeled his fervor for seizing, raiding, burning, arresting, and just generally opposing all things “filthy.” They squared up against birth control activists, gay bathhouses, pulp magazines, regular magazines, books, booksellers, and even Mae West, the star of the Broadway show Sex.

But as the 1920s and 1930s progressed, the NYSSV’s attempts to uphold the Comstock Act started falling flat. Charges it brought were regularly dismissed, and it faced fines for making false arrests. The law was still enforced occasionally through the first half of the 20th century, but the religious outrage that Comstock embodied had receded.

A series of Supreme Court decisions in the 1960s and early 1970s put an effective stop to the enforcement of the Comstock Act, though the statute itself was never overturned. Other rulings legalized contraception and the ownership of obscene material. In 1973 Roe v. Wade established the constitutionally protected right to have an abortion.

The Comstock Act would lie dormant for the next 50 years, until the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June 2022, leaving the legality of abortion up to the states. Within a year doctors and activists from the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine in Texas began arguing that the Comstock Act made it illegal to distribute by mail mifepristone, a drug used to induce abortion and ensure safety during miscarriage.

The move was “part of this sort of stealth strategy to ban abortion nationwide,” Drexel University law professor David Cohen told the Texas Tribune in March 2023. “If it’s illegal nationally to mail . . . anything that is related to abortion, that would make it very difficult to operate an abortion clinic or to be an abortion provider.”

In December 2023 the Supreme Court announced it would hear a case involving the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine’s attempts to ban mifepristone, making this the most consequential abortion judgment since the court overturned Roe v. Wade. The judges will issue their ruling by the end of June 2024.

Reproductive rights activists warn the ban on mailing mifepristone may be just the beginning. By limiting the safeguards around abortion, anti-abortion activists have inadvertently created space for do-it-yourself abortion businesses to roar back to life.

Already a volunteer network has sprung up, transporting abortion pills across the border from Mexico to Texas. It’s a godsend for many women, but the circumstances are still imperfect. In 2022 the New Yorker relayed the experiences of a smuggler it called Anna and a pregnant eighth grader who sought Anna’s help. The teen still seemed disquieted weeks after her abortion.

“In other states, or under another law system, her grandmother could have taken her to a sexual- and reproductive-health clinic, where they could have had a conversation with her, taught her about condoms, given her birth control, and sent her home feeling empowered with more information,” Anna told the magazine. “Instead, she had to go to some random person’s house. I’m sure they did not feel safe or comfortable here.”

A trip to Madame Restell’s mansion likely wasn’t a 19th-century woman’s preferred option either. But as medicine slipped further into the control of moral fundamentalists, a network of whispers and palmed remedies passed off as medical care was very often her only option. With the revival of reproductive care restrictions and Comstockian moral crusades, the return of latter-day Restells may not be far behind.