Jonathan Fetter-Vorm. Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb. New York: Hill and Wang, 2012. 160 pp. $22 cloth; $14.95 paper.

The golden age of comics—when Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman came to life—also gave the world the Atom and the Atomic Thunderbolt. By 1943 Superman was being sickened by radioactive kryptonite, and a few years later he was battling Atom Man weekly on movie screens.

Comic-book writers in the science-fiction genre were naturally drawn to the awesome and terrifying power lurking inside the atom. These writers could trace their inspiration back to H. G. Wells, who had latched onto Ernest Rutherford’s half-joking warnings of the atom’s latent destructive forces. In The World Set Free (1914), Wells imagines a war between superpowers that drop atomic bombs on one another.

As the Cold War escalated, so too did its influence on comics. Most of Marvel’s heroes from the early 1960s derive their superpowers from one radioactive mishap or another: Bruce Banner turns Hulk after being hit with a nasty dose of gamma radiation; Spider-Man’s abilities are transmitted to Peter Parker through the bite of an irradiated spider; and members of the Fantastic Four are mutated in all sorts of bizarre ways after a flight through cosmic rays.

In the 1980s such writers as Frank Miller and Alan Moore began plumbing the pessimism and philosophical consequences of the Cold War and nuclear-arms proliferation. The threat of nuclear annihilation steadily builds through Moore’s Watchmen, which takes as its central motif the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock. With each issue the world ticks closer to the brink. The most memorable character from the comic is Dr. Manhattan, a godlike antihero spawned from a physics experiment gone wrong. (He’s the naked, blue guy who in place of a third eye burns a Bohr model of hydrogen onto his forehead.) Moore’s work tackles the social and psychological toll the nuclear threat takes on humankind and perhaps what the bomb says about our very nature.

There can be no doubt that Moore’s depictions of a world locked in the fear and paranoia of nuclear holocaust are well known to graphic novelist Jonathan Fetter-Vorm. But Fetter-Vorm, creator of Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb, takes a markedly different approach in his exploration of the making of the bomb and its consequences. Trinity is a work of nonfiction, and while Fetter-Vorm doesn’t ignore the moral and ethical ramifications of the bomb entirely, the author is much more interested in the historical, political, and scientific forces that brought about the bomb. He wants to understand the hows and whys of the bomb, not so much what the bomb means. To that purpose Fetter-Vorm places the Trinity test literally and figuratively at the center of the book.

Afraid that Nazi scientists might develop a nuclear weapon, U.S. and British scientists began exploring the possibility of an atomic bomb in 1939. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 the United States resolved to build the bomb first. In three-and-a-half years scientists designed and produced the world’s first atomic weapons and developed refining methods for the uranium and plutonium needed to fuel them.

Relying on archival photography and first- and secondhand accounts—many of which will be familiar to readers with a passing interest in nuclear history—Fetter-Vorm makes clear the massive amounts of money, energy, and organization needed to pull off such an enterprise in secret. Two of the men most responsible for this feat were U.S. Army General Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project, and J. Robert Oppenheimer, the project’s scientific leader. Fetter-Vorm sets these two as a sort of yin and yang of discipline and creativity. In the author’s telling it took both Groves’s hard-nosed logistics and Oppenheimer’s charm and scientific eloquence to produce the bombs that would end the war with Japan.

The U.S. Army tested one of those bombs in the New Mexican desert on July 16, 1945. The code name for the test was Trinity. It was the first time a nuclear device had ever been detonated.

Fetter-Vorm has a knack for conveying the science behind these weapons through language and imagery comprehensible to the average reader. As at least one scholar has noted, the comic book is an unusual visual medium: stories are told linearly, but unlike film or television viewers, comic-book readers take things at their own pace. Boring parts can be skimmed, and complicated or extraordinary scenes can be pored over. Nowhere is this trait better illustrated in Trinity than in the depiction of the science and technology behind the bomb. The motif that strings many of these explanations together is dominoes. Toppling dominoes are used to demonstrate the mechanisms of a chain reaction and to explain why uranium-235 is such an ideal material. The thinner (less stable) the domino (atom), the more easily it will fall (fission). In this imagining (and now in the reviewer’s imagination) uranium-235 is a mere sliver of a domino, ready to fall with the gentlest push. Iron, the most stable element, is drawn as a squat, stubborn cube.

But these dominoes carry a double meaning in Trinity. While representing the order scientists were imposing on nuclear forces, they also convey the disorder unleashed. Such imagery implies that the Manhattan Project set off a much larger chain reaction, one well beyond the control of those who tipped over the first domino.

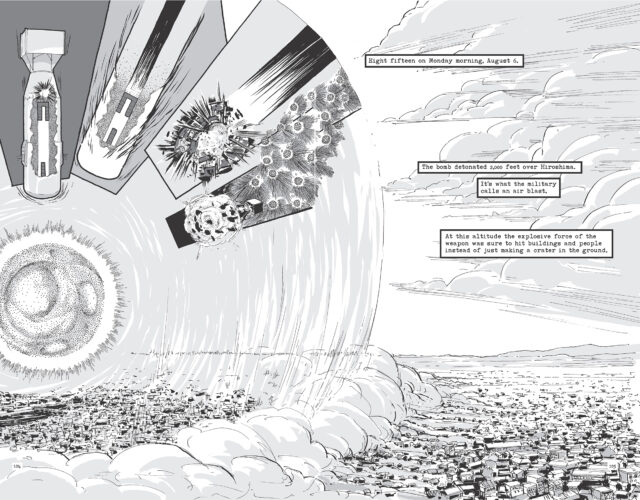

The second half of Trinity is devoted to the weeks leading up to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings and the short- and long-term effects of those events. Fetter-Vorm delves into the military and geopolitical considerations at play in President Harry Truman’s decision to use the bomb. Reenactments of the bombing missions and physical and ethical implications of that action close out the book. The narrative, while evenhanded, evokes the horror of the atomic bombings and the fire bombings of Japanese cities that preceded them.

The recounting of the Hiroshima explosion is indicative of the sparse and evocate narrative throughout:

Just as concisely, Fetter-Vorm recounts the Cold War chess being played before the war’s end and its role in Truman’s decision making. If using the atom bomb could force Japan’s quick surrender, Truman reasoned, it would keep the United States out of an uneasy alliance with Stalin and might keep the Communists’ Eastern aspirations in check. And while the bomb was sure to kill thousands of Japanese civilians, preventing a land invasion would save thousands of American lives.

Many scientists, haunted by reports of radiation sickness and images of nuclear destruction, abandoned the Manhattan Project soon after Japan’s surrender. Fetter-Vorm taps Oppenheimer to voice the misgivings of these scientists.

Oppenheimer went on to join the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, the organization that succeeded the Manhattan Project, but he devoted much of his time to warning the public of the threats of nuclear proliferation and tried to persuade the U.S. government to abandon atomic weapons altogether. (Other scientists, such as Edward Teller, were already busy designing bigger, scarier bombs.) At the end of a series of dark pages depicting the Trinity explosion, Fetter-Vorm has Oppenheimer utter his now-famous quote from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The quote conveys as much of Oppenheimer’s famous egotism as it does true pathos. But near the close of Trinity, Oppenheimer delivers what might be a more revealing thought, one taken from a speech he gave to the American Philosophical Society just five months after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki:

Oppenheimer and others foresaw the makings of a terrifying arms race. As relayed in Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s American Prometheus and re-created in Trinity, a troubled Oppenheimer told Truman, “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.” But Oppenheimer made a miscalculation when he challenged Truman on moral grounds. Truman was repulsed by what he considered Oppenheimer’s “cry-baby” hand-wringing. In American Prometheus the president later remarks, “Blood on his hands, dammit, he hasn’t half as much blood on his as I have.” Truman declared he never wanted to see Oppenheimer in his office again.

With that, Oppenheimer lost any chance of influencing the man best able to prevent America’s pursuit of an atomic arsenal. Scientists did turn some of the Manhattan Project’s scientific discoveries to peaceful uses, but the bombs that ended one war almost immediately fueled a much longer and potentially more dangerous war. The promise of the atomic age would quickly degrade into a time marked by paranoia and dread.