Leaving Limitations Behind

Scientists’ memories of migration.

Scientists’ memories of migration.

Why did a scientist in Poland decide to go to the United States for her PhD studies? What did a physician-scientist from Kenya think of hospitals in the United States upon his arrival? How did a student from China adjust to graduate studies and the social environment at an American university?

Answers to these questions—and others—can be found in the oral history collection at the Science History Institute’s Center for Oral History. The interviews we conduct with scientists and engineers are typically structured as life histories, meaning an interview spans the interviewee’s entire life. We ask them questions about their education and scientific work, but also about their childhood and interests outside of work. By asking questions about life experiences beyond the lab, we get a fuller understanding of how different parts of an interviewee’s life have shaped who they are and the work that they do.

A topic that has often come up in the course of oral history interviews—and that we are now asking about more intentionally—is immigration. By capturing immigration stories in oral history interviews, we hear scientists and engineers reflect, in their own words, about the role migration plays in their personal journeys and careers, thus shedding light on an aspect of their lives that might not be evident in their publications, patents, or personal papers.

Today, we are sharing excerpts from oral history interviews in our collection that highlight the challenges and opportunities interviewees faced throughout their immigration journeys and in their scientific work. These firsthand accounts allow us to better understand why and how individuals immigrated to the United States, how immigrants have adapted to and made a positive impact on American society, and how migration benefits scientific development.

In her interview, Lilianna Solnica-Krezel discusses the challenges she faced when conducting scientific research in Poland in the 1980s:

Solnica-Krezel wanted to conduct scientific research in a place that could provide proper funding, resources, and equipment. She decided that leaving Poland and going to the United States for advanced study would benefit her experimental work. Solnica-Krezel is one of numerous scientists in the oral history collection who migrated to the U.S. in pursuit of institutions, mentors, funding, and equipment that, often due to disparities in access to scientific resources, were unavailable or inaccessible in their countries of origin.

With access to laboratory facilities at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, Solnica-Krezel studied genetics and completed a PhD in oncology. Now a professor, she studies vertebrate gastrulation, the process of embryonic development of animals with spines, with a focus on zebrafish.

Enrique Iglesia was a teenager when he and his family left Cuba and went to Mexico in the hopes of eventually making it to the United States. In his interview, Iglesia explains how his experience in Mexico played a role in determining the kind of career he wanted to pursue:

Iglesia’s experience supporting his family in Mexico through manual labor shaped his desire to excel in his studies. He studied at Princeton and Stanford, and became an accomplished chemical engineer with a specialty in catalysis, contributing to the field through work in industry and academia.

Many immigrants have a difficult time obtaining the documentation and legal approval needed to come to the U.S. Roald Hoffmann discusses how he and his family changed their surname in an attempt to beat the quota system so that they could immigrate to the United States from post-World War II Poland.

Hoffmann’s account—and those of others in the collection—demonstrates immigrants encountering barriers to immigration and using their skills and ingenuity to find ways around or through the system. After arriving in the U.S., Hoffmann attended public schools in New York City. He went on to study chemistry and physics, eventually becoming a theoretical chemist. He was awarded the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Immigrating to America is not always a smooth journey. For those whose native language is not English or who didn’t grow up with American culture, adjusting to the new environment can be particularly difficult. Yixian Zheng left Chongqing, China, to study molecular genetics as a PhD student in Columbus, Ohio. She recalls the cultural and language barriers being so formidable that she initially thought she wouldn’t be able to complete her degree.

But Zheng also belonged to a supportive community of Chinese students, including her future husband, and they helped each other achieve their dreams. She earned her PhD in molecular genetics and her work on the microtubule, a tube-shaped protein structure in the cell, led to multiple collaborations with scientists in America.

Richard Honig immigrated to America to escape Nazism. He thought he would enjoy freedom in the United States and pursue studies in physics at MIT. But as a German national, America viewed him with suspicion:

The treatment he received in the new country was dispiriting, but he was able to find a mentor who helped him get through this trying period of becoming an American citizen. Honig is one of several Jewish German immigrants in the oral history collection who were classified as “enemy aliens” during World War II and thus, paradoxically, found their freedom curtailed in the country where they sought refuge.

Despite encountering challenges, Honig and these other scientists were able to make an impact. Honig designed an early secondary ion mass spectrometer, an analytical instrument that measures ions, and contributed to other innovations in the field of mass spectrometry throughout his career.

Getting used to American society was not always an arduous process of navigating an unfamiliar culture. For example, Vishva M. Dixit had a surprising encounter that reminded him why he decided to leave Kenya to pursue his career. He remembers his feeling of amazement when he began his medical residency at a hospital in St. Louis:

Dixit thrived in this new hospital environment and in an educational environment where he could learn about and conduct scientific research. He went on to study cell death and thrombospondin, a family of glycoproteins that facilitate the growth of new blood vessels, and has led research on cancer therapies. Medical advances resulting from his work have benefitted patients in the United States and around the world.

These are just some of the many immigration stories in our oral history collection. There are many more stories that have yet to be recorded. These narratives help us understand the interactions between migration and science that have not only affected the lives of scientists and engineers but have also transformed American science and society.

Want to engage with more stories of science and immigration? You can view excerpts about immigration, scientific work and achievement, and the full collection of interviews in the Oral Histories of Immigration and Innovation project.

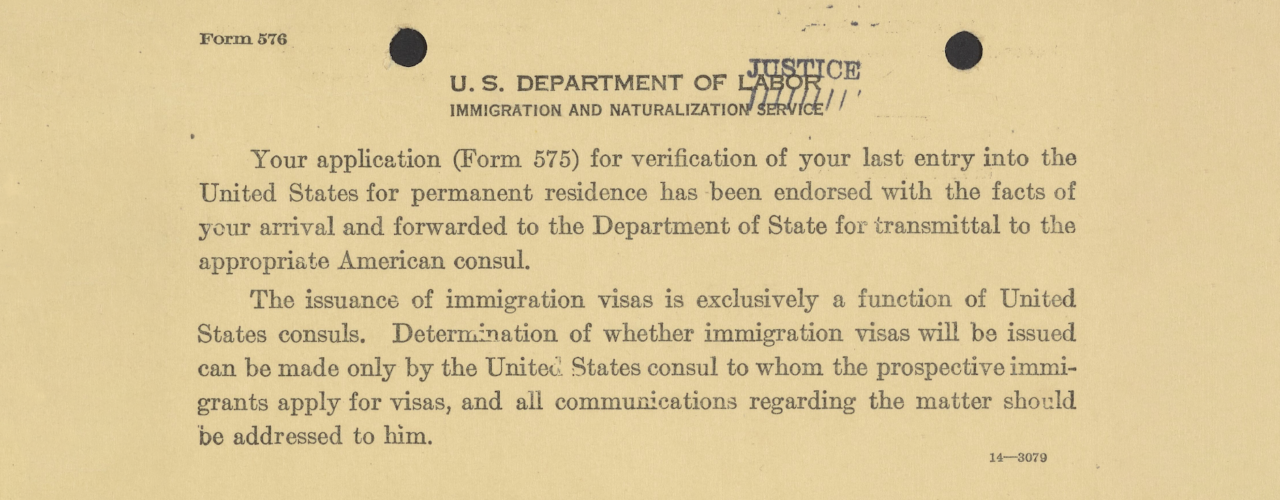

Featured image: Back of a postcard to Jewish German chemist Max Bredig from the U.S. Department of Labor and Justice, 1940.

These audio excerpts were created in conjunction with the Migrating Science: Stories of Immigration and Innovation ExhibitLab and the Oral Histories of Immigration and Innovation project, both of which were made possible by the generous support of the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.

Thanks to Mia Jackson who designed and created audiograms for the ExhibitLab. Sarah Schneider, Rachel Lane, and Shuko Tamao selected audio excerpts from oral history interviews to include in the ExhibitLab, and David Caruso provided curatorial guidance about the interview excerpts. Molly Sampson, Ashley Augustyniak, and Erin Gavin also assisted in the curation of the exhibition.

Pets aren’t allowed in our museum or library, but you’ll find plenty of them in our collections.

Why oral history is critical for the history of science and engineering.

A chemistry curriculum with bonds beyond the molecule.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.